All considered, this week, I feel pretty prepared. I set off for Hyderabad and my new post at Woxsen University tomorrow and I’m packed and ready. I’ve even written this…

It seems like a moment to look back on my very first trip to Hyderabad, way back in 2010 and to give you a bit of background to where I’ll be writing from for the next twelve months. Not all of my posts will be about Hyderabad, or even India, but I expect and hope that every one of them will be shaped by my experiences there and the people I will meet (and see again).

Some of them definitely will be filling in parts of this story as I share my explorations with you, but for now, this is an outline.

For me, it began as a fairly new PhD student in 2010. I arrived in Hyderabad and spent quite a lot of time trying to find this place:

The problem was that there are two major museums in Hyderabad. (There are plenty of others, which I’m looking forward to visiting, too). One of them is the State Archaeology Museum, which is the one I wanted to get to. The other is the Salar Jung Museum, which is much more popular among foreign tourists and was therefore where the very helpful auto drivers I travelled with thought I meant. As a result, I got a fantastic tour of the city and did actually go around the Salar Jung, which is lovely and otherwise I might not have done. I was much more linear in my approach to travel back then!

The other place I spent quite a lot of time was here:

This compound was, in 2010, the State Department for Museums and Archaeology and it has a beautiful little circular museum in the middle of the numerous offices, from which I was seeking various letters of permission. What I remember most, though, is that everybody was extremely friendly and always invited me to join them for staff tea breaks if I happened to have a long wait before the Minister was available. I was very young, very junior and always travelling alone. It made a massive difference and is one of the reasons why going back to Hyderabad feels a lot like going back to one of my a-bit-like-home places.

Mainly, I was in the city to see coins from around the first half of the first millennium CE, but that is not the period that made the Hyderabad of today, which I therefore, saw more like a tourist. Now I’m looking at it anew was a historian with much broader interests and as somebody about to be able to take students on field trips to the city!

The are on which Hyderabad was eventually built has been inhabited since the Neolithic (which in south India means roughly 3000-1000 BCE). However, it only seems to have become important in regional politics under the Kākatiya Dynasty, who ruled the area equating roughly to the modern federal states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, with some territory in neighbouring states, from the 12th to the 14th centuries. They, in the early 13th century, built a fort at Golconda, a halfway point in their empire, which gave them a defensive outpost to protect their western lands.

Golconda fort still stands today, though most of the existing fabric dates from a still later period.

There isn’t much evidence that what is now Hyderabad was much more than a fortress until the late 15th century. At this point a governor for a large northern polity, the Bahamani Sultanate, re-fortified Golconda, with the core of the stone-built fort you can visit today. Apparently, the earlier fortress on the site was mud-walled.

Whether this governor already had plans that involved a really big fortress, or whether it was just lucky chance, 22 years later, he decided to rebel and declare independence from the Bahmanis. Sultan Quli Qutb-ul-Mulk (also often referred to in English-language writing as Quli Qutb Shahi), became the first ruler of the independent Qutb Shahi dynasty. At their height, the Qutb Shahis ruled over roughly the same area as the Kākatiyas had centuries before.

Golconda was their palace was well as their fortress, and the city of Hyderabad grew up around it, along the banks of the River Musi.

In the 17th century, the Qutb Shahis were reincorporated into a more northerly power. This time, it was the Mughal Empire. In 1714, the Mughals appointed a new governor, Asaf Jah I, who became the founder the Asaf Jahi dynasty. From the late 18th century, the Asaf Jahis, who also used the title ‘Nizam’ became effectively independent rulers of Hyderabad (both the city and its surrounding region).

The Nizamate remained independent until the declaration of Indian Independence and its incorporation into the Union of India in 1947, although in the 19th and early 20th centuries there was a British ‘supervisory’ presence in Hyderabad.

In Hyderabad today, it is the history of the Qutb Shahis and the Nizams which give the city its most obvious flavour. Both dynasties were Muslim rulers over a majority Hindu rural population, which caused intermittent religious tension and violence. It also gave rise to a unique culture, sometimes referred to as Deccani, or, in its more local forms, Hyderabadi, which combines elements of local South Asian and West Asian, Persian culture. The result is distinctive forms of language, architecture, food, music, dance and literature.

The other factor which made Hyderabad such an important cultural centre was money. The Qutb Shahis and Asaf Jahis, in particular, were well known as patrons of the arts, gathering writers, musicians, painters and scientists in their court. Substantially underpinning this patronage was the diamond mines of Golconda, one of the most productive in Asia. In fact, Golconda was the likely origin of the Koh-i-Noor diamond, now a controversial part of the British crown jewels.

Today, Hyderabad is a bustling city of around 7 million people, with an especially prominent technology sector (one district is even called Hi-Tech City). It is also the state capital, but which state has been a big part of its recent history, and mine.

When the states of India were re-organised in 1956, Hyderabad became the capital of a state created on the grounds of common language: Andhra Pradesh was defined as being the majority Telugu-speaking part of independent India, covering roughly that footprint in the map (above) of the Kākatiya lands, though not extending quite so far south as Kanchipuram, where the majority of people speak Tamil. However, almost from the start, the linguistic unity of Andhra Pradesh sat awkwardly alongside deep cultural differences between the coastal strip of the eastern Deccan and the more arid, rural inland area, around Hyderabad.

The campaign for an independent state of Telangana was at its height when I first travelled to the city. I remember turning up at the State Museum at least twice, clutching my appropriately signed letters of permission, only to find that it was closed because of rallies happening in the wide avenue right outside. There were posters about it all over the campus of the University of Hyderabad when colleagues there made me welcome and generously pointed me to books and articles I was not aware of.

In 2014, Telangana became a new federal state of India, with Andhra Pradesh now comprising that coastal region. Thus, Hyderabad went from being the capital of Andhra Pradesh to the capital of Telangana. The Andhra Pradesh State Archaeology Museum became the Telangana State Archaeology Museum and the Andhra Pradesh State Department for Museums and Archaeology became Heritage Telangana. (The change was both to make something a bit snappier, but also to reflect the full remit of the department, including things like landscape and site conservation and public presentation of heritage).

And all of this is, in a roundabout way, how come I get to be going back to Hyderabad tomorrow…

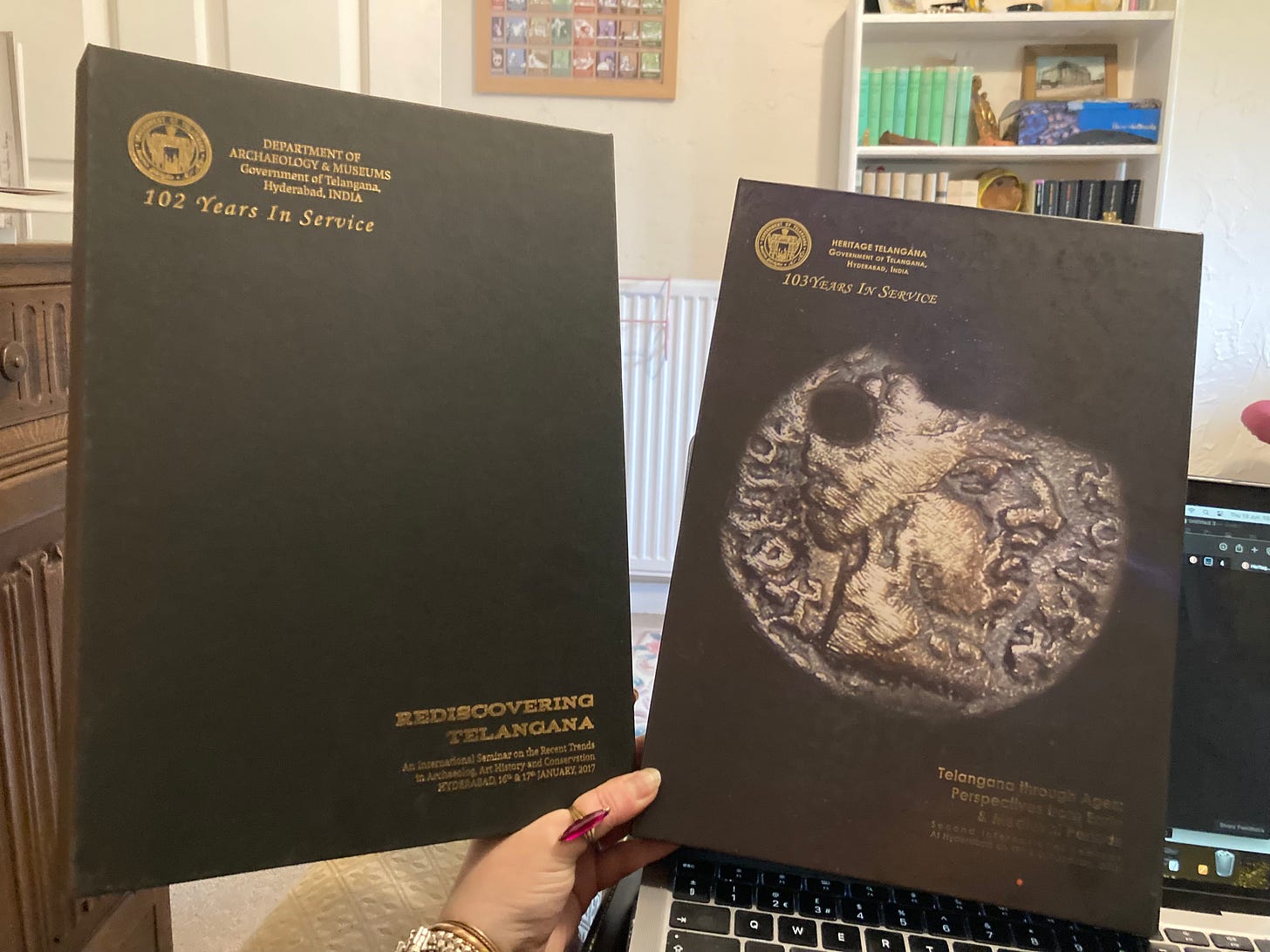

In 2017, what was still the Department of Archaeology and Museums (now of Telangana), held an international conference to celebrate and explore the very long history of India’s newest state. I was invited to speak and, honestly, nearly said no. I love Hyderabad and the conference sounded wonderful, but it was right in the middle of a teaching term and I ended up flying out and back over the course of four days then heading back into the classroom not really sure what day of the week it was.

Then, in 2018, the conference was held for a second time. For a second time I was invited, thought about saying no, but couldn’t resist getting back to Hyderabad. At this conference, the rebranding to ‘Heritage Telangana’ was announced.

At both of these conferences, I met many lovely and interesting people, but I am especially grateful that one of them saw something in the horribly jet-lagged, by 2018 definitely slightly burned out, and still pretty junior numismatist sitting in the hotel lobby waiting for our bus to the conference venue. Prof. Rekha Pande is a titan of gender history and medieval history in India, and in scholarly networks worldwide. She is also wonderfully generous, kind and interested in everything.

She is one of those senior women scholars I have been privileged to connect with in my career, whose mentorship and fundamental belief that we can only be historians if we are human beings first, makes the world a better place.

We began to collaborate, organised a conference in London and speak fairly regularly and, at some point I mentioned that I would love to work in India. So, last October she forwarded me an email I might otherwise never have seen, advertising a post at a university I had not yet heard of. The rest, dear reader, is about to be history!