This may seem like a question with an obvious answer, but it actually isn’t. This week I’m looking forward to participating in a workshop about bi- and multilingualism in historical settings. It has already made me think harder. And, predictably, I’m going to be talking about coins.

One purpose of bi/multilingual texts is, pretty clearly, to enable people who speak (and read and write) different languages to understand what is being communicated.

Using various languages in public places, on signs, coins, government documents, etc. is, often very clearly, also about giving recognition and concrete status to communities. This might be about stitching together a political balance between a coalition of groups who think of themselves (or thought of themselves when the decision was being made) as being different. Alternatively, it might be about a dominant group (politically, numerically, militarily, or anything else) giving some kind of public viability to a less dominant group.

Are comprehension and recognition the only reasons for such public multilingualism, though? What about this?

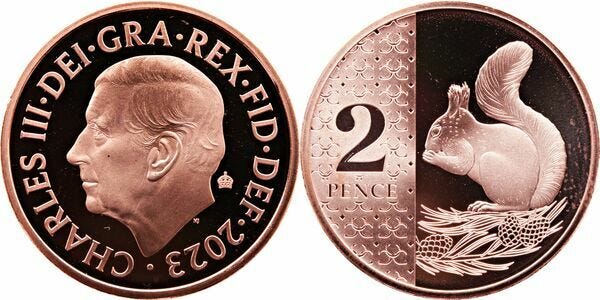

There are two languages at work here. The information you might think people need to use the coin - what it is worth - is in the majority and official language of the state, English. Then there is the other bit.

CHARLES III. DEI. GRA. REX. FID. DEF. 2023.

There are a lot of abbreviations here, so let’s lay that out in full:

CHARLES III DEI GRATIA REX FIDEI DEFENSOR 2023

Latin is not a spoken language in the UK. It is no longer an administrative language. The words on this coin are not meaningless. Their meaning (Charles III, by the grace of God, king, defender of the faith) is deeply significant to the unwritten constitution of the UK, but putting them in Latin is not to help anybody understand what they say!

The words are in Latin because it is a prestige language, for reasons linking the present to antiquity, via the Middle Ages. The abbreviations are part of a standard repertoire for writing Latin in public inscriptions (including on coins). Using Latin, and its abbreviated forms, and all uppercase letters, links the modern United Kingdom to the historic grandeur of the Roman Empire.

Now, the Latin on UK coins is something I’ve thought and written about quite a bit before, but I’d never thought about it hard enough in relation to another example of a coin design that has taken on new dimension because of thinking about multilingualism on coinage:

This is the design of a two rupee coin issued between 2007 and 2011 as part of the so-called ‘Hasta mudra’ series. Hasta mudra refers to the complex system of hand signals or shapes made in traditional South Asian dance, yoga and sculpture and drawings. The ‘Hasta mudra’ series of coins included this, a one-rupee coin (with a closed fist and a raised thumb) and a 50 paisa coin, with a hand making the shape of a closed fist.

As with all post-independence Indian coins, the words are in the two official national languages of India: English and Hindi. In addition, the numeral is in Arabic, rather than Hindi script. However, the relationship on these examples between the value of the coin and the hand shapes adds a further level of meaning.

The mushti mudra, or closed fist, on the 50 paisa coin has no immediate relationship with the number 50, but both the shikhara (mountain peak) on the one rupee coin and the kartari mukha, or two finger mudra, on the two rupee coin, pretty obviously do. The mudras and the value of the two most common coins in use, especially among the urban poor in India, overlap and reinforce one another.

I have previously used this as an example of the ways in which the state in India could use symbols on coins to communicate both with illiterate users and with people who have neither Hindi nor English as either a first language or, in some cases, as a functional language. What I did not discuss enough on those occasions, though, is that this was not necessary.

People all over the world, since coins were first invented in around the fifth century BCE, have been using coins which either had no words on them at all, or had words on them which the majority of users probably could not read.

Using coins depends on so many things other than words: weight, size, shape, colour, overall design, context. That is why, in the UK we don’t really need to notice that some of the information on our coins is in an abbreviated form of a language most people don’t read.

In South Asia in particular, multilingual populations have been using coins for centuries. Historically, those coins had inscriptions in various languages, sometimes in two or more, or sometimes had no inscriptions at all. Since Indian independence in 1947, the population of the Indian state had managed perfectly well for 60 years with coinage and notes marked only in Hindi and English, and with Arabic numerals, without needing hand symbols on coins to understand their value.

What was going on in around 2005/6 in India, when the Hasta mudra series would have been designed and produced, which might have inspired this additional layer of visual communication, alongside written information?

One of the things about coin design is that the answer is rarely simple. Some coins are released to commemorate a specific occasion. In these cases, we can discuss the choices of the artist in representing that occasion, but the link between what was going on and the design is usually pretty clear.

Most of the time, however, there is no straightforward line to draw between the circumstances in which a coin is designed, the numerous different parties who take part in designing a coin (the artists who may submit options, the committees who may choose them, the engravers who execute them, etc., etc.), and the design itself.

Rarely, especially in the more recent past, we may have official or unofficial records explaining the choices made, though these are also written by particular people for particular reasons (let me tell you, some time soon, about the problem of numismatic deer…).

Instead, as with any other historical source, it is up to us to try to join the dots in a way that seems sensible, and that is what thinking about bilingualism on coins got me doing.

2005/6 was, in many ways, a difficult time for India, witnessing various domestic acts of terror, often with sectarian overtones. At the same time, though, it was a fairly prosperous time, in which the Indian economy was opening up. If we look at the Hasta mudra coins in this context, do those symbolic hand gestures make more sense? They are not about making the coins more usable, but what about the other reasons why multiple languages might be used?

Can we see them giving visibility or recognition to any particular group? The poor and illiterate were definitely part of the constituency that the government needed to speak to. It was vital to persuade them that they, too, would benefit from the economic changes taking place in India. Could using a symbol easily understood by people with no training in reading or writing have helped to give additional dignity and recognition to other forms of communication? It seems probable.

Should we see the Hasta mudra coins as speaking to communities in India which have not historically felt represented by either Hindi or English? This, too, makes a kind of sense, but not necessarily specifically in 2005/6. There definitely are communities in India, which identify strongly with languages other than Hindi and English. This has been true since independence and earlier, though. It might be seen as part of a broader context in independent India, rather than an urgency in the early 2000s.

What about the symbolism of the Hasta mudra system, as part of the cultural achievement of historic India? This is another promising possibility. As India opened up economically, and domestic unrest flared around lines of religion and culture, we can see a growing concern in some political circles, from the early 2000s onwards, with defining an Indian character and culture, closely connected with India’s heritage, including intangible practices, such as dance and yoga. The use of mudras on coins very plausibly signalled this recognition and elevation of traditional practices as part of an official, public Indian identity.

The Hasta mudra coin design did not last that long (although they remain in circulation, so look out for them if you are shopping in India!). They were issued only for five years, before reverting to traditional designs. This perhaps points to another very different way in which coins communicate - by being the same. The more consistent a coin remains, the less anybody needs to worry about things like what the words on it say or who can read them. The longer a coin remains the same, the more people tend to trust it. The better it works as a coin.

Innovation in coinage therefore isn’t usually a good idea, from a monetary perspective. For historians, though, time-limited design innovation is fantastic. However uncertain our guesses, it is a window into how people - often people at the upper levels of a state - wanted to communicate with large populations. This is something that has always fascinated me about coins, but looking at them from a new direction can be a valuable reminder that there are many more ways to communicate than through words, and even words themselves can be more than language.

Words can be symbols, pictures, the markers of a community identity. Words can be what we expect to see in particular contexts, so that we don’t really see them at all. Sometimes they are most effective when we don’t have to read them.