Today I have been watching the coronation of King Charles III of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. This is not a post about my (or anybody else’s) views on either Charles, the British monarchy or monarchy in general.

The significance of the coronation for millions of people makes it a matter of historic interest to me. As a historian, and especially a historian with a specialism in the Middle Ages, it was also a fascinating spectacle.

Today’s ceremony was complex, intricate and far too long to discuss in a single post. I may have future thoughts! For today, though, what mainly stands out for me are the ways in which tradition and historicity are constructed through echoes and imitations, linking actions across time and creating layers of overlapping meaning. And, as a scholar of the material world, it was visual and material echoes and inter-textualities that struck me most forcefully.

What follows is a meander, a musing, an exploration of the way things look. It is also about the reasons why they look that way, and the ways that an eye on the distant past weave them into a thicker history.

Let’s start with this moment, that rang in my medievalist mind:

Charles, anointed with holy oil (that had been blessed in Jerusalem), has been dressed in golden robes of state, seated on a coronation chair (not the coronation throne of Edward the Confessor, at this point), and has been presented with various insignia of state, some of which he is holding. There are plenty of descriptions of these insignia and their significance all over the web (try out this guide, and support regional journalism in the UK!). But what echoed in my mind was this:

Recognise that silhouette? The ruler enthroned, knees apart, wearing a crown topped with a cross, a sceptre marking a strong diagonal line upwards…

This representation of a Christian ruler became common in the sixth century CE. On the coin above, it is an image of a medieval Roman (Byzantine) emperor, though the coin itself was struck under the rule of early Muslim rulers in West Asia. Before the invention of a distinctive Muslim coinage, with no images on it (definitely a future post about that!), local community leaders and regional governors under the earliest Muslim rulers in the Levant simply continued to produce coins that people would recognise. That meant coins with the Christian Roman ruler whom the Muslims had only recently driven out of these territories.

The photograph of Charles and the image on the coin are not quite identical, though (top Art Historian points if you spotted the difference).

Charles holds two sceptres, while the emperor on the coin holds in his right hand another object. It is one of these:

The orb of state, often called by medievalists a ‘globus cruciger’ (just means a ball with a cross on it), does feature in the British coronation ritual, but the monarch is only presented with it for a short time before being given… another sceptre. Nevertheless, this too was a striking medievalist echo.

The globus cruciger represents the rule of Christ (the cross) over all of the world (the ball), and appears in Roman depictions of emperors almost as soon as they converted to Christianity in the fourth century. As such, it is one of the oldest symbols of Christian lordship and monarchy. It is also a direct claim by the British monarchy to similarity to, or perhaps succession from, the Christian Roman emperors.

It can be seen on this thirteenth-century gold coin of Henry III of England, which very closely imitates Roman coin imagery, as we see above.

Let’s back out from the details of what the king holds and the centuries-long claims to Christian rule that those objects evoke. There were other models that the Middle Ages offered up.

Take this sixth-century mosaic in the apse of the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna (Italy): the four figures, most wearing white, standing to either side of the seated ruler.

When the Roman emperor Constantine I adopted Christianity as his favoured religion, a process began of fusing ideas of rulership on Earth and imaginings of God’s rulership in Heaven.

The Christian emperor came to be seen as God’s viceroy on Earth, so his behaviour was meant to be modelled on Christ, his court on the court in Heaven. In turn, depictions of Heaven came to mirror the realities of courtly behaviour on Earth. Thus, the bishops who flank King Charles during the coronation service mirror the two angels who stand beside Christ in this mosaic. The posture of Christ and the posture of the crowned king are similar. The white robes of the angels and the bishops are alike.

I’m not suggesting that anybody designing the British coronation ritual, for Charles or any earlier monarch, ever saw or consciously copied this mosaic in Ravenna. Instead, the ritual that took place this morning in Westminster Cathedral was using a visual language of rulership that has been spoken for millennia.

Now, I made a point earlier about Charles not sitting in the coronation throne when our starting photograph was taken. Instead, he is sitting in a coronation chair, which looks (under all those robes) like this:

The part to pay attention to here, as a medievalist, is not the deep red fabric or even the heraldry (well, you can pay attention to that as a medievalist - I’m just not that medievalist). It is the distinctive curved legs, like two semicircles placed one on top of each other to form the front and rear supports.

They matter because they look a lot like this:

The term for this design of chair is a curule chair. They were actually a kind of foldable camping stool, with the seat slung like a hammock between the two sets of curb ed supports: easily collapsible and therefore used a lot on military campaigns. As a result, they came to be associated, from the early Roman Empire onwards, with emperors and senior generals. That is why this coin of the emperor Titus, from the first century CE shows the emperor on one side and, on the other, a curule chair with a laurel wreath for victory on its seat. It was a symbol of the victorious monarch.

Historians often talk about inter-textuality. It is when one piece of writing quotes from or uses themes from another piece of writing. Think of that moment in one of the new Star Wars movies (if you like Star Wars), when parts of the audience gasp and grin and cheer a bit because C3PO said something that was almost identical to something he said in one of the original movies. (The Star Wars movies are, in fact, massively intertextual, with echoes of the Bible, Beowulf, Shakespeare… But that is definitely another post, by somebody else.)

Intertextuality is powerful because, when we recognise a quote or a theme from somewhere else, we understand what it means in its current setting, but we also remember what it meant in that other context. This can intensify its significance or perhaps cause us a frisson of contradiction. If somebody refers to a couple as a real ‘Romeo and Juliet’, we know they mean that they are deeply in love, but we also know that things didn’t end well for Romeo and Juliet…

I use the idea of inter-textuality a lot when thinking about material culture things we make and do and look at, because things also speak to us. Or, more accurately, we use things to speak with.

In a ceremony as laden with symbolism as a coronation, echoes of rulership past - the obvious ones and the tiny ones - evoke and create authority. Repetition is the essence of tradition, and familiarity is central to the emotional reactions that tradition elicits. Repetition also enables us to say new things, just as we express new ideas using mostly old words, subtly changing their meaning or the way we put them together.

Perhaps the highlight of the whole ceremony for me as medieval historian was this:

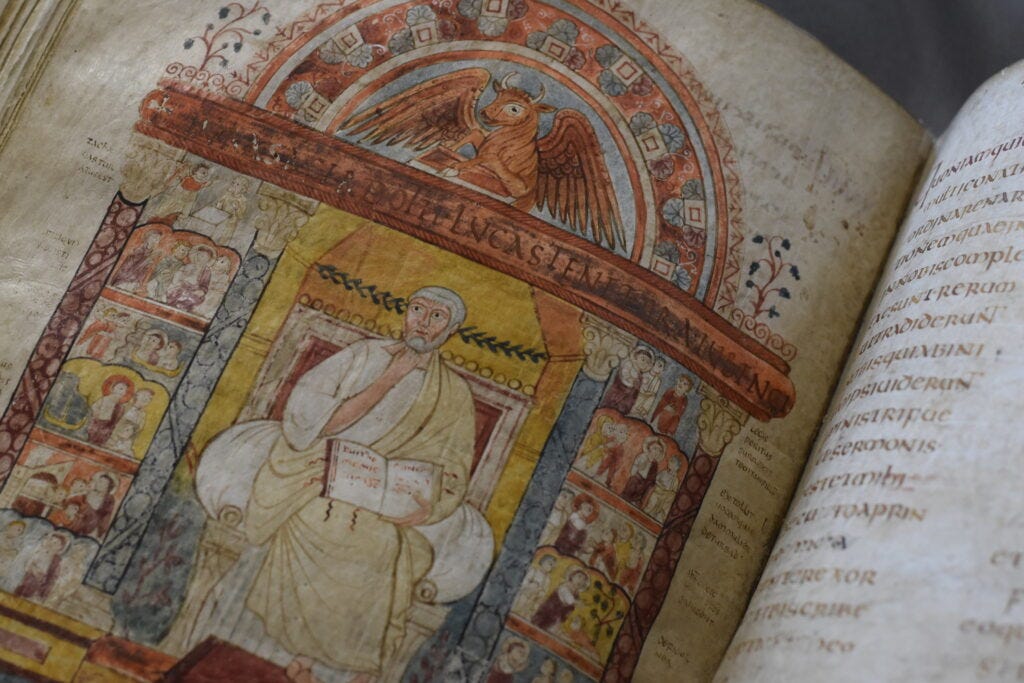

The sixth-century gospel book of St Augustine of Canterbury is now kept in the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and you can find out more about it here. Sufficeth to say here, that for a medievalist, it is extremely cool and very old. It is rare for objects to survive from the earliest post-Roman centuries in Britain, which are so colourful, so well-preserved and so closely connected with known, named individuals events.

At the coronation ceremony, it was brought out and presented to Charles. Its presence asserted a physical link between the modern Anglican Church and the sixth-century Christianity of St Augustine, quietly making the same argument that underpinned much of the Protestant Reformation - that Protestantism was not an innovation, but a return to an earlier (and purer, Protestants argued) form of Christianity.

All of that is very interesting to me, and hopefully to you, but where I want to wind up this post is with the image of Saint Luke in this gospel, seated in a very similar way to our images of rulers, but without the curule chair or the insignia of state, and wearing robes of pure white.

From the earliest Christian centuries, white clothing came to be associated with purity, innocence, simplicity and holiness. Think of our white-clad bishops, mirroring white-robed angels. Christ is often depicted wearing white. King Charles was stripped to a white silk shirt before his anointing. Luke sits, contemplating the word of God, with images around him of the stories he will write, wrapped in a long white gown.

And during the coronation, we also saw and heard the performance of the Ascension Choir, of a new gospel composition, created for the event. Their white robes spoke the deeply established Christian language of simplicity and purity. Their position, turned towards each other in a circle, communicated that their performance was directed towards God, rather than the king - the court on Earth giving praise to the court in Heaven. It also evoked the egalitarian ideal of both earliest Christianity and the non-conformist church communities which have played a huge role in modern black British culture and spirituality. The choir and the gospel book performed in a strange, centuries-long harmony.

The significance of artists of colour, performing music so closely associated with black culture and the Christianity of resistance and liberation that developed among marginalised communities was an intentional statement about the diversity of modern Britain and the value and integral place of that diversity in modern Britain. It was a striking example of the ability to use old symbols to say new things.

As with anything anybody says, we can ask if it is telling the whole story, or if there are other ways to tell that story. The coronation was a highly scripted account, from a very particular perspective of what Britain is, where it comes from and how it hopes to develop in the future, but for a historian the process of telling is as interesting as the message.