Hello, hello,

This week and next, I’ll be posting remotely and will be slower to reply if you message me or comment. (But please do: I will get back to you.) I’m on holiday and will tell you more when I get back. Inevitably we’re off somewhere with a good density of historical remains!

To leave you with something to chew on, though, I’ve been thinking existentially: if history doesn’t remember you, did you really exist?

You might be surprised how often this question crops up if you’re a historian. The relationship of ‘history’, meaning ‘the past’ and ‘history’, meaning ‘records and stories of the past’ is long and complex. Things get even messier when ideas like memory get involved. Is history a form of social memory? Can we really ‘remember’ things we didn’t experience ourselves? If history is collective memory, who decides what’s included?

If you tell somebody that you’re a historian, a pretty common response is that people ask you questions about famous figures. I’ve been asked for my opinion on, among others, Napoleon Bonaparte, Charles I (of Britain), Queen Victoria (of Britain and various other places), Gandhi, and Shakespeare. My answer is always that they aren’t in my period and anyway, I’m not really a historian of famous figures. Another thing that happens quite a lot is that people talk about their own lack of history-worthiness.

But what are your (or my, or anybody’s) chances of being remembered by history? Honestly: slim. Whoever you are and whatever you do, you don’t have much chance of your name living on eternally and you don’t have much control over it, either.

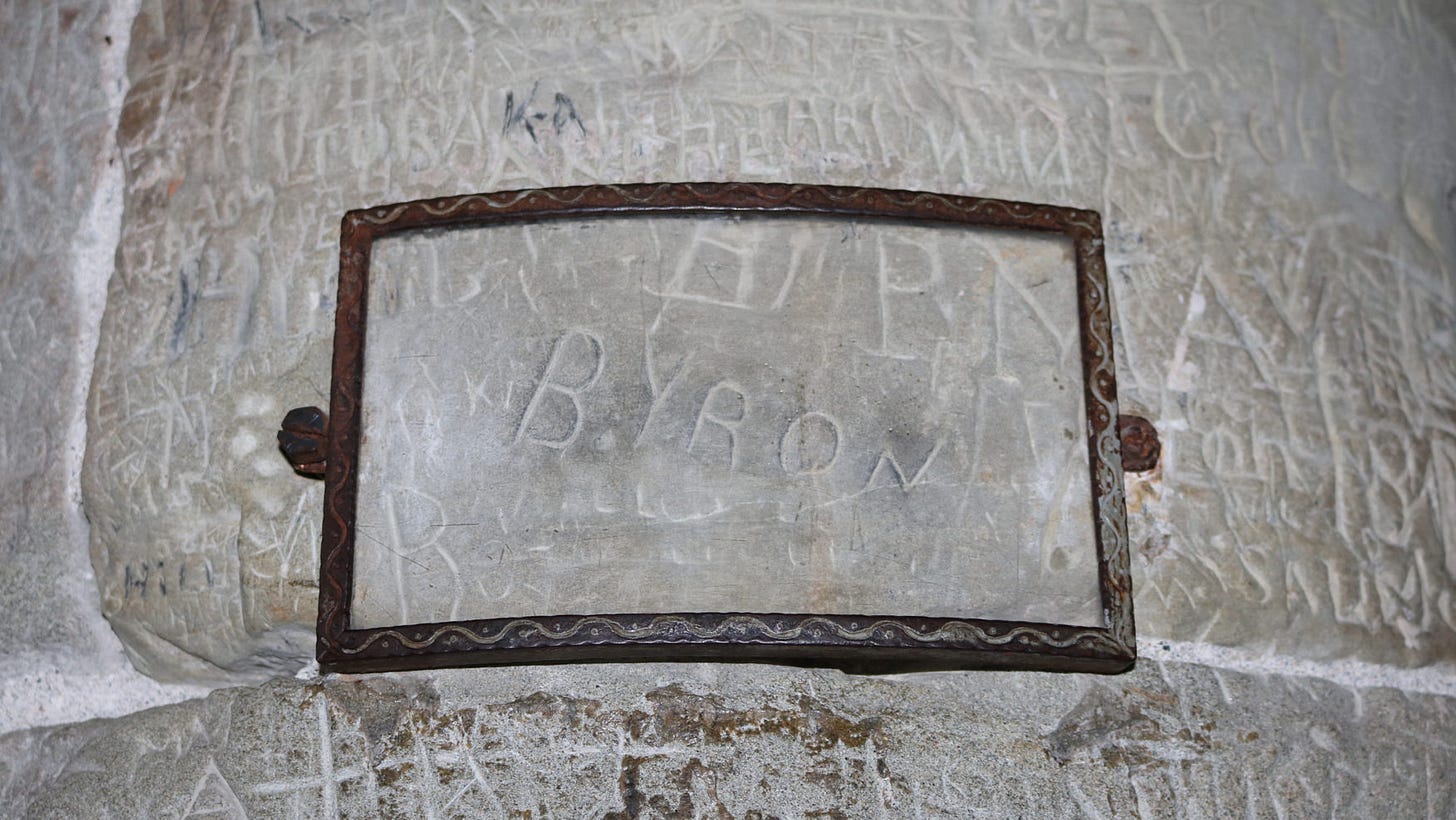

While the 19th-century poet, Lord George Gordon Byron, carved his name into historic buildings from York to Athens, his friend and fellow romantic poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley, wrote about the futility of historic memory in ‘Ozymandias’:

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Meanwhile, an ancient Greek writer, often considered the originator of history writing, Herodotus, stated that he wanted to ‘prevent the traces of human events from being erased by time, and to preserve the fame of the important and remarkable achievements produced by both Greeks and non-Greeks’. Nearly 2500 years later, Herodotus is are arguably more famous than any of the people he wrote about.

Historical memory generally attenuates over time: still being remembered after a couple of centuries is a lot easier than being remembered after a couple of millennia. Oral traditions need to be relearned one generation after another - they are vulnerable to interruption. Written documents are vulnerable to other dangers. They get lost, burned or simply thrown out. People forget how to read languages that have passed out of everyday use and words on stone crack and crumble. More importantly, the bigger stories that famous people fit into - the plays in which they are the leads - lose their relevance and fade away, taking their leading men (and sometimes women) with them. You see, none of us is ever famous, or forgotten about, on our own.

You might think there are things that people do that write their names in history - winning battles, being kings or emperors, building cities or inventing things that change the world. And yet, the inventors of countless things that have changed the world, from the wheel to gunpowder and the compass, are anonymous (and probably numerous). And plenty of battles have been won, kings and emperors crowned and cities built without conferring all that much immortality on the people involved.

The Roman emperor Justinian I, the South Indian Maharaja (great king or emperor) Rajendra Chola I and the Sasanian Persian Shah-an-Shah (king of kings, or emperor) Khusrau II are well known bby scholars of the regions and period I study but they’re not exactly household names. Yet each of them bestrid their worlds like colossi. By comparison, figures like Richard I Plantagenet (often called ‘the Lionheart’) or Charlemagne don’t necessarily have a better case for having prizes named after them or being played by Sean Connery.

The difference isn’t what they did. It was things that happened centuries later, far out of their control. Chances of fortune meant that Richard and Charlemagne became heroes and founder figures of states (England and France, respectively) that went on to become powerful. They became characters in a play that continues to matter to people, while Justinian, Rajendra and Khusrau have not played such a central role in later people’s stories.

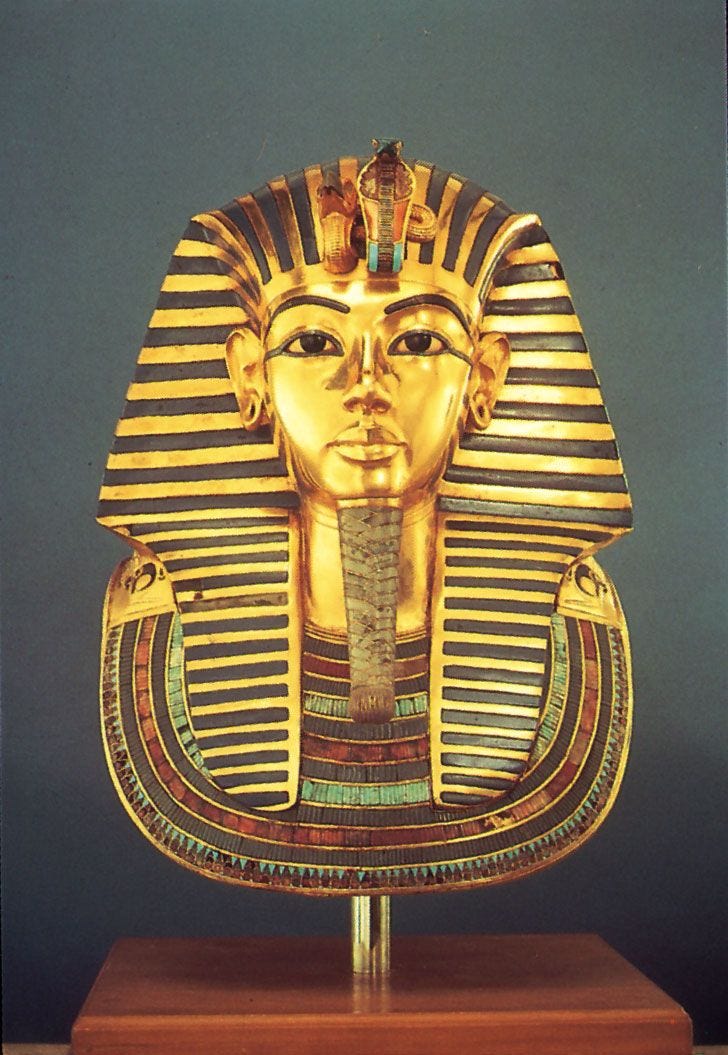

There are other kinds of dumb luck, too. Perhaps the most famous Egyptian pharoah is a young man who didn’t do all that much in his life but amidst all the centuries of looting in the Valley of Kings, his tomb happened to go unnoticed until Howard Carter and his team stumbled on it. Tutankhamun became the face of ancient Egypt.

Even with random chance at play, of course, all the people I’ve named were born to wealth and power. That chance, more than any other, improves the odds of your name being remembered. But what does being remembered actually mean, anyway?

Take any of the figures I’ve menioned. Plenty of ink has been spilled about who they were ‘really’ (more about Tutankhamun, Richard I and Charlemagne than Justinian, Rajendra or Khusrau). From the details of what they did to what they thought or felt about their own lives, historians, filmmakers, novelists and artists have specualted, reserched and hypothesised. Mostly, though, they exist as myths, not people. We will always know more about what other people thought or felt about them, often long after they died, than about how they personally felt or thought or even acted.

With famous writers, we might stand a bit more chance of glimpsing that personal world. After all, they left us records of their innermost thoughts, but even then, what survives is usually incomplete, partial, frequently ficitonal.

But all of this raises further questions: how much does a name really matter? Is it true that a name is everything we are?

In February 2021, I remember reading an article about the recording of births and deaths. In the context of the Covid 19 pandemic, which was raging at the time, how states record people was suddenly newsworthy. It turns out that only 8 countries in Africa at that point had robust systems for recording deaths. From the perspective of public health, the benefits of reliable record keeping were obvious. The article also pointed to other challenges from not having secure records of births and deaths. It makes all kinds of things, from knowing how many children will need school places, to planning housing harder. Since it is often the poorest and most marginalised who aren’t recorded, it also worsens inequalities. How can a government intervene to improve people’s situations if it doesn’t even know they exist? So, I’m not against record keeping, but…

…as a historian, this was the quote that stuck with me:

This not only robs them of a "right to an identity", in the words of William Muhwava - the head of demography at the UNECA based in Addis Ababa - it also means that lessons are not learnt.

Especially studying periods before the very recent past (and before the normalisation of modern record-keeping), it had never occurred to me to that anybody might think that a person’s identity might not matter (or even exist!) if there wasn’t a record of it. It seems a bit like saying that, if I didn’t get a receipt, I didn’t actually do the shopping yesterday. But I still have food in the fridge and I still had a chat with the lady at the till and I still forgot the toothpaste.

Looking at Ice Age art, that I wrote about last week, we don’t need to know a name to encounter a real person, looking at the world and taking time to preserve a moment. Scholars and the press quickly gave ‘Ötzi’ his name because it seemed strange to know so much about somebody and to work so closely with them and not to have anything to call them, but the name is an invention. We could invent a new one for him or give him a code or an artefact number and it wouldn’t change a single thing about his life, his death or his remains.

The same is true of history more generally. Obviously, I think history is important and fascinating, or I wouldn’t spend so much of my life doing it. But history, like records of births and deaths, is about the present not the past: it is about what insights or inspiration we choose to take from what happened before. That is why history being accurate matters so much. It’s what stops us lying to ourselves (or others), telling ourselves that things are the way we want them to be intead of how they are. That doesn’t mean there is only one way to tell an accurate story, though.

What we choose to tak about, the lessons we draw and who we are talking to play their part. If somebody asks for the story of your life, even assuming you aren’t a pathological liar, you might still tell a different version to your future mother-in-law, your new boss, a stranger on a train or a group of new friends in the pub.

Whether we know the names of people in the past, whether we tell one story or another about the things they did, is a bit like the question of whether I got a receipt when I went shopping. There are all sorts of good reasons to get a receipt but, no matter what, the food is still in the fridge, I still talked to the till assistant, I still forgot the toothpaste.

We can write histories or lose them, record people’s names or not, and the past will still have happened exactly the way it did, just as our lives are real, right now, and shaping the world around us, no matter who might remember or how. The record of our lives is not in a ledger. For most people who have ever lived, it isn’t carved in stone. Your odds are better if you’re rich or powerful, but the world isn’t made by the wealthy and powerful.

I don’t study the history of single figures (which is one reason I don’t have much of an opinion on Napoleon Bonaparte), because they aren’t really where history happens. Sometimes they can nudge affairs more one way than another. Mostly, though, their names are labels we give to things other people did: Justinian I rebuilt the Hagia Sophia, Khusrau II reformed the Sasanian tax system, Rajendra I expanded Chola power across the Bay of Bengal. Justinian probably never lifted a trowel, Khusrau likely didn’t tot up a single tax return, Rajdenra almost certainly never left the peninsula. Their personalities are lost while their names live on as a shorthand for thousands of other people, who built and farmed and lived.

The record of all of those lives is the world around us. They did not, as Karl Marx famously said, live life on terms of their choosing:

Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Karl Marx, 1852

And so it is for us and will be for the generations who follow.

But we all make the best we can of the lives we have. We can glimpse the ones who came before us in the mortar of buildings, the lines of a painting, terraces on a hillside, maintained and abandoned by new generations making their own decisions about what to do. And of course, we see them in each other. So, if you’ve ever worried that your life might not be the stuff of history, take heart. The past belongs to all of us and was made by everyone who lived it. And we can always change the stories we tell about it, including whether we focus on great names or the great works of nameless individuals. All that matters is that we try to make them accurate.