Known/Unknown

The historian's currency

Hello, hello,

Wherever you are, I hope you are having a good Friday. This week I’m writing to you from the road, probably, when this actually goes out, somewhere just outside Milan on the way to Paris. There will be more to follow about Sicily, where I’ve been for the last two weeks (and which I wrote about last week), but for now, I want to think about a question that somebody on this trip asked me, which is both fundamental to the doing of history and fiendishly, deliciously complex once you start poking at it. How do we know what we don’t know?

Known Unkowns and Unknown Unknowns

Donald Rumsfeld, then US Secretary of Defense, made famous in 2002 the concept of known unknowns and unknown unknowns, though the idea, as a logical proposition, had been examined by ancient and medieval philosophers. These days you’ll hear mention of ‘known unknowns’ and, more rarely, ‘unknown unknowns’ all the time history shows, podcasts, in lectures and at conferences. They are catchy, useful shorthand, but sometimes it’s helpful to reverse the lens - to go from the catchy, useful shorthand back to the specifics.

The specifics in this case came up when talking about two things, one of them pretty big, the other smaller. The first was how do scholars know that we do not know much about what was going on between roughly 1200 BCE and roughly 800 BCE in Sicily (and, indeed, much of the Mediterranean)? The second was how did people pay for the building, decorating and ongoing use of burial plots in underground catacombs in 5th-century CE Syracuse, and, if we don’t know, why don’t we know?

These may not seem like connected questions. They are both about Sicily, but could apply, with only minor tweaking, in a lot of other places. They are about times separated by over a thousand years and one of them is about a very specific aspect of daily life while the other one is a bit more of an ‘everything’ question: we know less about pretty much everything that might have been going on in Sicily c. 1200-800 BCE than at other times. But at their heart, they speak to the same issues:

How do we define the edges of knowledge?

What is the threshold for knowing, versus surmising, speculating or guessing (which are all legitimate things for historians to do)?

What do we do with what we don’t know, so that we can still make progress with what we do know?

The Coin of Knowledge

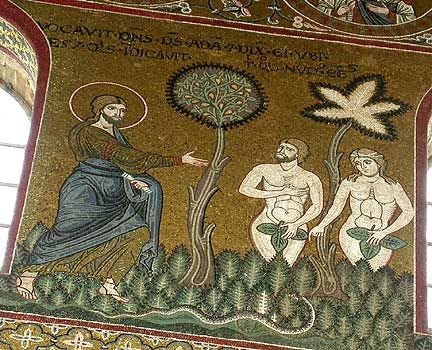

Known and unknown are inseparable. They are two sides of the same coin. It is only because we know things that we can be conscious that we don’t know things. That’s what the famous image of Adam and Eve in their fig leaves in Christian art is really all about.

Taking the fruit of the tree of knowledge makes the first humans in the Christian creation story aware that they are naked. Ashamed of their nudity, they cover themselves but their fig leaves, ironcially, give them away. If they had not eaten the forbidden fruit, they would not have known the difference between being uncovered or covered, or have known that one state might be considered better than the other. It’s a story that grapples with kinds of knowing that we mostly learn before we start thinking about it. Babies, after all, don’t know they’re naked. They might know that they are cold, but wrap them in a blanket or turn the heating up - it is all the same to them!

But if the unknown is simply the opposite of the known, then how do we really know something? Here, I’m going to leave Adam and Eve in their inadequate attire because I’m a historian, not a theologian, and how they knew that being nude was meant to be a bad thing is definitely more of a theological/philosphical question than a historical one. But how, to choose one of my historic case studies, do we know that we do know all that much about what was going on in Sicily before c. 1200 BCE and after c. 800 BCE?

Thinking about this exposes a bunch of extremely important things:

Knowledge is incomplete. Saying we know X doesn’t mean we know everything about X. It means we know something about X.

Knowledge is relative. Since complete knowledge of anything is effectively impossible, rating our knowledge of something as good, bad, better or worse, is always a comparison with how much we think we know about other things. And the ‘we’ here is really important because…

Knowledge is collective. Saying ‘we know’ anything about Sicily before 1200 or after 800 BCE is another shorthand. It really means ‘I believe that such knowledge exists somewhere in the world, that there are people who know it and that I could, if I tried hard enough, verify that knowledge personally’ (but mostly, I won’t. I’ll trust reliable sources who have summarised the evidence). When I talk about what ‘we’ know, I’m not usually talking about evidence I went out and found or that I personally examined and drew conclusions about. If I sometimes might be, because I’m a practicing historian, then I’m only talking about a tiny bit of knowledge in a much bigger pool, and I could only contribute much of my interpretation of it based on what other people had already found out about other things because…

Knowledge is connected and cumulative. Often, once we know a few things about a time or place, it is easier to know other things about it, making the gap between known and unkown bigger.

So, thinking about Sicily before c. 1200 BCE or c. 800 BCE onwards, there is an infinity of stuff we don’t know, from the names and lives of individuals to when, how and why different crops and technologies spread and how political alliances were formed. But we do know the names and some of the events of the lives of some individuals, the rough spread of some technologies, etc.

What matters about knowing something is that it provides a good comparison with what we don’t know. For around 400 years on Sicily, for example, c. 1200-800 BCE there are no inscriptions, no texts have been handed down telling us any stories, however mythic and there are not many sites that we can date to this time. What with knowledge being collective, I’ll be delighted to hear if some of this is becoming less true. It is not my core period of study so new discoveries might exist that I don’t know about but even if they do, they will still amount to less than we know about the periods before and after.

That is in part because of my final point: knowledge is connected and cumulative. Even if we suddenly found a new site, or (less likely) a new text that we could date to these 400 years, we would have a much emptier picture to place it in.

Take pottery, for example. Pottery sequences are crucial to how we (that collective we again) know really quite a lot about the ancient Mediterranean. They work like this:

Say you find a piece of pottery - usually broken from something else. How do you know what it was or when it dates from? If all you’ve got is one piece, you don’t. Too bad.

But what if you keep finding bits of pottery that all look alike - same coloured clay inside, some coloured glazes or designs on the outside, and possibly in similar shapes, such as flat plates or narrow cylinders? You cna often tell is something was a flat plate or a rounded bowl even from quite small pieces. Well, then you can start doing things like trying to put pieces together, or extrapolate from a curved edge how wide the rim of something must have been (here is a great video about doing exactly that, this time with pottery from North America but the principles are exactly the same wherever your pot sherds are from). You can start to recreate different objects rather than just bits of objects. That still doesn’t tell you when they were made though.

How about, though, finding lots of bits of pottery that look one way in certain kinds of sites (say, ones that have a particular, distinctive shape of building or use bricks where other sites use stones for building)? That might be telling you that these specific pottery objects were used at special kinds of sites or at a particular time. For now, you/we don’t know. It could be either. Maybe people built temples out of stone and houses out of brick, for example, and used different kinds of vessels in each, or maybe over time, people’s taste for brick or stone changed and so did their taste in pottery, but either way, we can now start building hypotheses about how these groups of evidence fit together.

Next, let’s say, we have enough sites with the same-looking kinds of pottery (and buildings) that we can start to notice that, pretty reliably, the stone buildings with pottery styles that look one way are underneath the brick buildings and bits of pottery that look another way? This is starting to look like stone buildings with one pottery style (let’s call it pottery Type A) are older than brick buildings with the other pottery style (let’s call it pottery Type B), because once the stone/Type A sites have finished being used, people built brick/Type B sites on top of them.

Ho, ho. And now the magic of connected, cumulative knowledge really gets going. Imagine you find a site with a brick building and some Type B pottery. There is no Type A pottery or stone building, but still, because you can compare it with other sites, you can be pretty confident that this site dates from the same time as other sites with brick and Type B, and is newer than sites with stone and Type A. Now you can start to take all the information from all the brick/Type B sites and cluster it together. Say one site has evidence for cloth weaving and another one has evidence for different kinds of farm tools and another one has some imported glass from Egypt and another one has pictures of people drinking wine painted on the pottery and so on and so on. If you only had one site, the chances are it wouldn’t have all of these things but together we’re building quite a complex picture of a society where people farm in particular ways, drink wine, weave cloth and import fancy stuff. And we know that it was a later stage in that local society than the stone/Type A phase.

At this point, we still might not have a clue when in real terms, each of these clusters of stuff was happening. Maybe stone/Type A was 500 years ago and brick/Type B was 300 years ago, or maybe stone/Type A was 3000 years ago and brick/Type B was 2000 years ago, but we can still know quite a bit about what those worlds were like.

I’ve written before about how we might go from step 6 to actually deciding when in real time things happened. You might find a handy inscription with a date on it, or a coin or you might do some scientific testing, and be able to link those answers to one of your layers (in this hypothetical example, either a stone/Type A layer or a brick/Type B site), or a text might tell you something that unlocks the key to a precise when, such as when a big, important building was constructed. And if you can do that, then what we don’t know suddenly comes into pretty sharp focus.

For the period before 1200 BCE, for example, there are sites across the Mediterranean with distinctive pottery, connected styles of art, and signs of societies importing and exporting ideas and stuff between themselves. Then, there aren’t really any of those things for a few hundred years. Then, from c. 800 BCE onwards, a different set of distinctive styles and techniques crop up and this time there are texts, too. Around this time was when Homer was writing his epic poems about the Trojan wars (set around 1200 BCE, so already a semi-mythic memory for the great bard), and the contrast with the period in between is even sharper. From c. 800 BCE onwards there are more sites, more objects, texts, inscriptions…

Even not knowing, though, when you have some knowledge around it, can become a ay of knowing. If, for example, you know that for 400 years or so, there aren’t really any sites with distinctive building styles or pottery then that is telling you that, for a while, people stopped doing things they had done before and would do again. There are limits to knowledge from absence but it is a starting point: were there suddenly fewer people, because of famine, disease, war? Was there some drastic change in fashions (for tents and wooden utensils, for example), or lifestyles (such as people becoming more nomadic)? Or did some disturbance mean that people found themselves without the time or the space in their lives to build permanent structures and make pottery? Some of these possibilities might seem less likely than others and, over 400 years, the answer is probably more than one, but we can see that something changed and we can start to speculate about what that might have been. And from there maye we can think about what kinds of evidence those scenarios might have left behind that you might not find without looking for them. By pinning down what we don’t know we can figure out new ways of finding out.

Buried Clues

It isn’t true everywhere, but in a lot of the Mediterranean, and in lots of other places besides, we generally have more evidence the more recently things happened. There are exceptions to that. Mainly I mean the Roman Empire in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, which just produced a massive amount of very distinctive looking stuff and a huge amount of written material that later generations thought was significant enough to preserve. Broadly, though, the closer to the present we get, the more stuff survives, partly because, especially from the 18th century onwards, socities have become more bureaucratic and industrialised, meaning more production of records and stuff, and partly because there hasn’t been as much time for the random chances that destroy records to happen to them (flood, fire, war, weevils, etc.).

Just how rare it is for lots of kinds of evidence to survive, though, is a bit counterintuitive in this day and age. We currently live in an information pandemic or paradise (depending on what you’re trying to do with it): data is everywhere, about almost everything, or so it seems. Want to know the national flower of Luxembourg? Its the rose. The gestation period of a possum? 15-16 days (or up to 17-19 days for the Tasmanian possum, which I now know, but didn’t 30 seonds ago, is different from other kinds of possum. I resisted finding out more about the many and varied kinds of possum and their gestational habits, but it was all there if I had wanted it!). We increasingly take it for granted that almost anything can be found in the collective knowledge base, which is to say we (our actual selves) tend to assume that we (the sum of everything humans know) know about most things. It isn’t true and it is usually less true the further back in time we go.

Take grave administration, for example…

The fundamental parameters of grave administration are pretty stable over time: in cultures where people prefer to bury their dead, there is a fairly steady supply of people needing to be buried and a need for a certain amount of labour to create suitable places. Different levels of labour and skills will depend on things like how hard or soft the local soil or stone is and whether the cultural preference is for large or small, deep or shallow, decorated or plain graves.

Another fairly constant parameter is that death is notoriously unpredictable. As a result, either a culture needs to ensure that everybody, from the moment they are born, has a suitable grave waiting for them, or that one can be provided on potentially quite short notice. The latter has tended to be the preferred method, presumably because it provides more flexibility around migration, people dying while temporarily far from home or people’s tastes, means and, indeed, size changing over their lifetime. All of this means that, in lots of socieities with a preference for burial, creating graves is an economic rather than a personal activity: people pay (or provide other economic incentives) for other people to dig graves rather than doing it themsleves when a loved one happens to pass away.

But in cultures that prefer burial, graves aren’t just a question of labour. They are also a matter of real estate. Is the land owned by a government or a municipality and then assigned to people as they die? Is it collectively owned, with the whole community having rights to be buried somewhere? Are people buried on the residential property owned or rented by their family? Or do people buy grave plots just like buying a house or an orchard? This isn’t an exhaustive list of possibilities, by the way. But a society with any kind of system for assigning land rights and a preference for burial is probably going to have thought about how land for burial fits into wider systems for deciding who gets to do what on which land.

This question came up lately while wandering around the ancient/medieval catacombs of Syracuse.

The catacombs of Syracuse were mostly used from the early centuries CE onwards for burials, up to the early modern period, although with signs of earlier use as stone quarries (first creating the underground cavities) and as water storage, and later use right own to the 20th century as air raid shelters. They are now entirely free from human remains but still preserve a sense of how the rituals of burial were arranged. And in some places wall paintings survive showing how people, especially richer people, liked their tombs to be decorated.

Looking at one of these painted tombs, probably from the 5th century CE, one of my fellow visitors asked the not-unreasonable question of how much such a nice spot would cost. The answer is we don’t know, not for these particular tombs in Syracuse. But there must have been records, countered my fellow traveller. And everything we might speculate from what we know about 5th-century Sicily or extrapolate from catacomb burials elsewhere suggests that there probably were. We might image, as my companion did, very large, very detailed ledgers. This was a literate, record-keeping society with well worked-out rules about land ownership.

One of the best indications that, in the Roman Empire more generally, rock-cut tombs could be privately owned comes from the bible. Following Christ’s death on the cross, one of his followers, Joseph of Arimathea, provided his own tomb, from which, according to the biblical narrative, Christ then emerged three days later following his resurrection. The theology of this has preoccupied scholars for thousands of years but economic and social historians have also pointed out that this suggests that Joseph had pre-paid for his own tomb. And since he presumably did not spend much time there in the usual run of things, there must have been some record that he owned it.

Those records no longer survive for any first-millennium burial ground that I know of. Why? Probably because they were made on fairly fragile material, whether papyrus or wood or wax tablets, and because they weren’t of lasting value, at least not at this kind of time scale. For context, some - a handful - of the most enduringly tenured aristocratic landowners in the UK, which has not done badly for record preservation, all considered ( not all that much fire or flood and minimal war and weevils), can trace their family possessions back to just before 1066 CE, so still about 500 years less than records would need to have survived for the Syracusan catacomb. And those records going back to c. 1066 are about something that has historically been worth putting a lot of effort into documenting, i.e. revenue-producing land (usually in the form of rent paid by farmers). However sentimental a grave might be, it does not produce direct revenue and so, bluntly, the incentives for keeping track of graves have tended to be quite a bit lower.

Here we return to the two sides of the coin of knowledge. We know that we don’t have such records of burials in Syracuse only because we can be pretty sure that we do know such records existed, because we know more for later periods (including the present. Burial plots remain big business across much of Europe and beyond) and about other parts of the wider Mediterranean region in a similar period. The story of Joseph of Arimathea’s tomb became part of the story of Christianity and so there have been some strong incentives to preserve it, which would not have applied to other grave sites. And given that what we don’t know is functionally infinite and what we do know is all incomplete, connected, cumulative, relative and collective there is nothing wrong with doing what we can with what we do know, as long as we’re clear about exactly how we’re building our house of cards and about which cards are more load-bearing than others.

The story of Joseph of Arimathea suggests, since the fact that he is a welathy man is mentioned, that buying a private tomb wasn’t cheap. Records from more recent societies point the same way. But do we mean closer to 10% of average annual income or 2%… well, now we’re off the map. How we would even start to estimate average income in the ancient Mediterranean is an interesting question, that some scholars have attempted, but it contains plenty of useful guess work. Picking out numbers for how much we might factor tomb expenses into that would, in my opinion, and most people’s opinion (I think), just be picking numbers out of thin air.

But suppose somebody came along and said, ‘hey, we have all of this modern actuarial data about how much pretty rich people have spent over the last 100 years on burial plots’ (which I bet we do!). ‘How about if we applied that to the guesstimates that people have already made about the total income of a pretty rich person in the 5th-century Roman Empire?’ You could definitely come up with a number. I would call that number bunk. Or hokum. Or nonsense. Pick your pejorative term of choice. But that is a judgement call based on all of the relative, connected, incomplete, slippy-slidey lines between knowns and unknowns that this post is all about. For me, whatever number such a person came up with goes too far from things we can pin down with a piece of actual evidence. But for another scholar, so might saying that, if a rich man in the Levant had a private tomb, that might mean that private tombs in Sicily were mainly for the fairly rich. I think that is a pretty sensible extrapolation, given that the same factors affected the tomb economy in both the Levant and Sicily (which is to say, we have no reason to think that making a stone tomb was much easier or harder in one place than the other or that people died any more or less often). But you might disagree. You might prefer a higher level of certainty. Or you may think that saying that a private tomb cost 16.25% of the guesstimated income of a middlingly wealthy Sicilian in the 5th century because that is the average cost of a middlingly plush tomb in modern actuarial records from New Jersey (or wherever: these are not real numbers!) is a reasonable calculation to make.

I don’t agree but we don’t have to agree. As long as we’re clear not just about what we know and what we don’t - known and unknown are actually much harder to separate out than they first look - but about how we know whatever it is we think we know.