Men looking at women looking at men in a story about women reflecting men

Mary of Egypt, the male gaze and the historian’s challenge

Next week I’m giving a lecture to first-year students about a woman. She is interesting but at the same time, she isn’t really who we’re seeing. Her story poses all sorts of questions about sources that don’t tell us the things we want them to, and what they might be telling us instead.

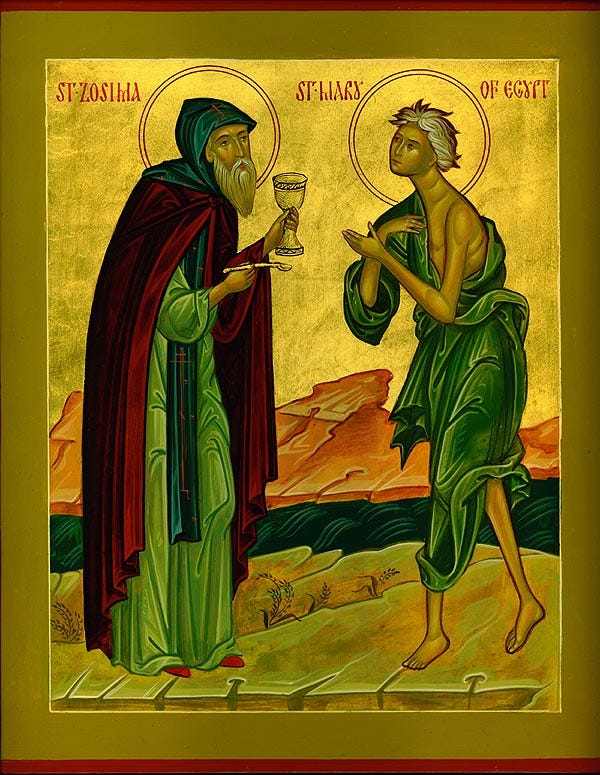

So, let’s start with what we have: a gripping tale of mystery, sex, redemption and a random lion. It all begins with a monk called Zosimas (also called Zosima, with the title Abba, meaning ‘Father’ in the quotes I’m using, which you can read in full here).

Zosimas was living in a remote and strict community in the wilderness near the River Jordan, some time in the early fifth century. One day, in the desert, he saw a ragged and naked figure. When the figure speaks, he realises that it is a woman!

"Why did you wish, Abba Zosima, to see a sinful woman? What do you wish to hear or learn from me, you who have not shrunk from such great struggles?" Zosima threw himself on the ground and asked for her blessing.

She asks him to toss her his cloak and, when she has covered up, agrees to tell him her life story.

Mary tells him that she grew up in Egypt and even as a child was tormented by insatiable lust, so that, at the age of around twelve she ran away to the bustling metropolis of Alexandria and lived as a sort of bizarre caricature: a prostitute who loved sex so much that she insisted men not pay her for it. (She insists, at length, that she never got rich and actually begged and spun flax to earn money for food, suggesting perhaps a hint of sympathy for women who sold sex as a last resort. It was clearly worse to enjoy it!)

Eventually, she had exhausted the men of Alexandria and decided that a major Christian festival in Jerusalem would be a chance for some fresh adventures. We can only imagine how Zosimas the monk felt while she described the voyage to Jerusalem as a near-continuous orgy.

I said… `Will they take me with them if I wish to go?' `No one will hinder you if you have money to pay for the journey and for food.' And I said to him, `To tell you truth, I have no money, neither have I food. But I shall go with them and shall go aboard. And they shall feed me, whether they want to or not. I have a body -- they shall take it instead of pay for the journey.' I was suddenly filled with a desire to go, Abba, to have more lovers who could satisfy my passion. I told you, Abba Zosima, not to force me to tell you of my disgrace. God is my witness, I am afraid of defiling you and the very air with my words."

Zosima, weeping, replied to her: "Speak on for God's sake, mother, speak and do not break the thread of such an edifying tale."

Even in the holy city, she carried on sinning, says the emaciated Mary, until one day she tried to enter the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, or the tomb of Christ. A mysterious force stopped her entering and only then did Mary realise how bad her choices had been. Confronted by an image of the Virgin Mary, she repented and was immediately able to enter the church.

Following the advice of a divine vision to ‘go across the Jordan’ and find peace, Mary went into the wilderness. When her food was gone, she ate what she could find. When her clothes wore out, she wandered naked, avoiding other people.

When Mary finished telling her story, she asked Zosimas to return one year later, on Holy Thursday (the day before the anniversary of the crucifixion of Christ) and to bring her the bread and wine of communion, representing the body and blood of Christ in Christian worship.

Zosimas does as she asks. She thanks him and tells him to come back again a year later. When he returns, he finds her dead, but undecayed, body in exactly the same spot, with a note in the sand beside her saying that she died the same day he gave her communion a year earlier.

At this point, a handy miraculous lion happens by and helps Zosimas bury her. Zosimas then tells his fellow monks in the wilderness the whole story, which was passed down until a Patriarch of Jerusalem wrote it down in the seventh century.

There is so much to find in a story like this, but even though it looks like a story about a woman (and that is one of the reasons it is included in the lecture series I’m contributing to next week), one thing we arguably cannot find in it is Mary.

Whether Mary of Egypt actually existed, or whether this is just an ‘edifying tale’, is largely, a matter of faith. As a historian, I am not here to say that somebody whose tale has inspired faith and devotion wasn’t real. There is no way to say for sure.

What I can say is that this story was written down several centuries after the events, and that, even if there was a real woman who really did live in the desert, the story of Mary of Egypt is about a lot of other things than Mary of Egypt.

Another thing we can say with quite a bit of confidence is that this story was written by a man, or possibly men, and probably for a mainly male audience. It is a story about men looking at women (or a woman) in order to look harder at what it meant to be men.

There are a few things that give away that male gaze.

For a start, the story is just so… extreme. If this were a story about a man being violent (to choose a characteristic often stereotyped as male) Mary of Egypt would be Rambo in a ‘roid-rage, in a tank… with a bazooka. Mary’s sexual appetites are the stuff of ludicrous fantasy.

On top of that, Mary’s vices are all sexual. She is, we are told, a terrible sinner, but she never shoplifts along the way, nicks her dates’ or money pouches while they’re sleeping or vandalises somebody’s garden. She isn’t a troubled teenager acting out or a woman who just doesn’t give a fig. She’s a sex drive in human form.

Finally, Mary’s life looks like, and therefore, in a piece of carefully crafted literature, we might suspect is meant to look like a weirdly feminised version of the ideal life of a male monk. She starts out compelled by the sins of the world, finds God, retreats into the desert, but ultimately needs the help and companionship of a fellow monk in order to achieve the highest state of holiness.

This last part - her taking communion with Zosimas - was likely a comment on a battle about what it meant to be a good monk, which had just about been won by the seventh century when Mary’s story was written down. The issue was whether it was better to be a starving hermit alone in the desert or living a regular, regulated life in a community with other monks. The communalists (usually called the cenobites) had won the fight and that is also the moral of the story of Mary.

And the story of Mary may also serve one further purpose for a male audience. If a woman, soaked in sin, can achieve this level of holiness, then step up, you slackers! A man should have no difficulty being even holier.

So what can we do as historians with this story about a woman who maybe wasn’t, or who, if she was, is nearly impossible for us to see past the refracted light of many male gazes (Zosimas, the writer and the men he intended to read it)?

One answer about stories of medieval saints’ lives (in general) is that, as they were meant to be believable, we can at least extract everyday details: we may not believe the miracles but we might infer that readers thought that it was pretty ordinary for people to take a ship on their way from Alexandria to Jerusalem.

While that is true of some saints’ lives though, it is a harder argument to make for Mary of Egypt. Okay, we know people sailed from Alexandria, but frankly, we already knew that from a tonne of sources more convincing than a monastic fantasy about a fifth-century 18-30s STD cruise.

Besides, this story wasn’t meant to be ‘set in the everyday’. It was set in the olden days of the people who first read it. Its settings are stereotypes, of the city and its heaving debauchery, and the desert, which swirls emptily around the two protagonists, a place where time and movement and life itself work differently.

Zosima asked her: "How many years have gone by since you began to live in this desert?" She replied: "Forty-seven years have already gone by, I think, since I left the holy city." Zosima asked: "But what food do you find?" The woman said: "I had two and a half loaves when I crossed the Jordan. Soon they dried up and became hard as rock. Eating a little I gradually finished them after a few years."

Another option is to recognise the story for what it is, not what it isn’t. After all, the sources we have are very often not about the things we wish they were!

This isn’t a story about everyday life in the fifth century. It is not a story about women. It isn’t even really a story about Mary of Egypt. But it is a story about monks. It is a peek into a world in which men were monks and women existed as temptation, either away from or, our writer hoped, towards the divine.

It is a story about the goals of men who dedicated their lives to God in the fifth to seventh centuries, and the rewards they might get in return: Mary’s ability to survive on almost no food, the fact that she knew the time of her death a year before it happened, so that she had time to prepare herself, and even her sexless, emaciated appearance were seen as gifts from God to those who could leave behind the illusions of the world.

And it is part of a bigger a story about what it means to be a good man, or a good woman and the fact that those ideas can never really be separated, even, apparently, by men who had chosen to live nearly alone in the wilderness:

After crossing the Jordan, they all scattered far and wide in different directions. And this was the rule of life they had, and which they all observed -- neither to talk to one another, nor to know how each one lived and fasted.

The monastic moral of the story in the seventh century was that, even if Zosimas and his fellow hermits had been heroic and admirable, people actually do better depending on one another, and that even the best can learn from somebody else’s struggles. And those feel like lessons still worth something today, even if they aren’t the ones we might wish for when we first go hunting for Mary the woman.

If you are interested in reading more about the original text of the Life of Mary of Egypt, and about some of the interpretations of the text that I’m summarising here, the best place to go is this collection of ten lives of women saints, translated and discussed in a fantastic introduction by the wonderful Alice-Mary Talbot.