Hello again!

Need some coffee and a little historical pick-me-up?

As usual, it’s bring-your-own coffee but hopefully this little beauty will brighten up your day as much as it did mine when I found it.

Before I explain why it made me so happy, a massive thank you, a heartfelt apology and a hopeful declaration.

A massive thank you: to all of my subscribers, new and old, paid and free. It means the world to me that you are interested in things historical and in finding out some of them from me!

A heartfelt apology: the university teaching year has its own rhythm and September and October are always busy but for reasons I don’t need to bother you with, this year has been absolutely bonkers. I’m sorry for the silence, but I think I have a cunning plan…

A hopeful declaration: at least until January, I am not going to be able to post regularly with anything that needs lots of images or references. That doesn’t mean I’m not thinking about the past, so what I’m going to try is this: each week I’ll just check in and talk to you about what I’ve been thinking about. If you have been, too, let me know in comments or mail me.

Now, back to the world’s oldest map of India…

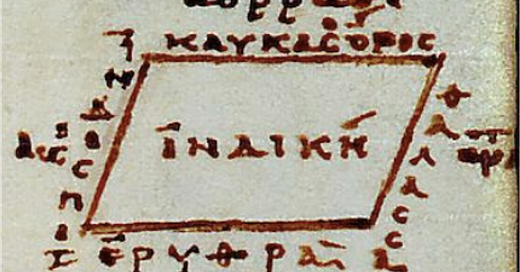

This is a sketch map drawn in the margin of a summary of a world geography written by a Greek-speaking Roman man called Strabo in the first century BCE/CE. The scribe, who was writing out this summary in the ninth century CE, was clearly trying to make sense of what Strabo says about India: that it is shaped like a rhombus with the rivers Indus in the west, the Caucasus mountains to the north and the Erythreian Sea (as the Western Indian Ocean was called in both Greek and Latin) to its south and east.

I love the glimpse it gives of a person thinking, probably more than a thousand years ago, trying to get to grips with how the world fits together. Whether it is the oldest or not, this map of India is immensely special as a document of human curiosity and knowledge building.

There are two reasons, though, why I’m fairly confident of the claim that it is the oldest map of India.

First, not that many maps survive from before the tenth century. I haven’t seen them all, by any means, but I’ve got a pretty good sense of their general range, especially from Europe, North Africa and West Asia. There are some contenders for preserving older ways of representing India, but they exist as copies of older material, drawn after the tenth century. I’m only claiming this as the oldest surviving map.

Second, my claim is intentionally limited. If I said this was the oldest surviving map of South Asia, i.e., the area now substantially covered by the Republic of India, there is a very good chance that I would be wrong.

For example, travellers from East Asia, from at least the fourth century CE onwards, journeyed to South Asia to collect original Buddhist scriptures. As a result, East Asian mapmakers definitely knew of South Asia and its location. Very few maps from before the tenth century survive in East Asia either, but I know them less well than the material from further west, so I would be on thin ice.

Fortunately, fascinating as these maps are, they don’t really matter to my claim. Map makers in East Asia (or, indeed, South Asia) would never have referred to the subcontinent as ‘India’ in the ninth century, or for many centuries after that.

The term originated in Greek, before being taken up in Latin. In Arabic the label ‘al-Hind’ derived from Greek and Latin, but mostly seems to have referred to the region around the River Indus, rather than the whole subcontinent. It was European trade and colonisation, from the fifteenth century onwards, that exported the label ‘India’ to other languages.

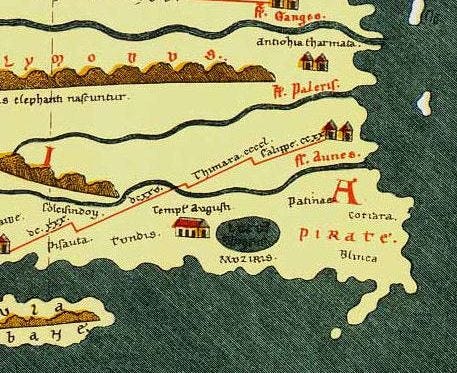

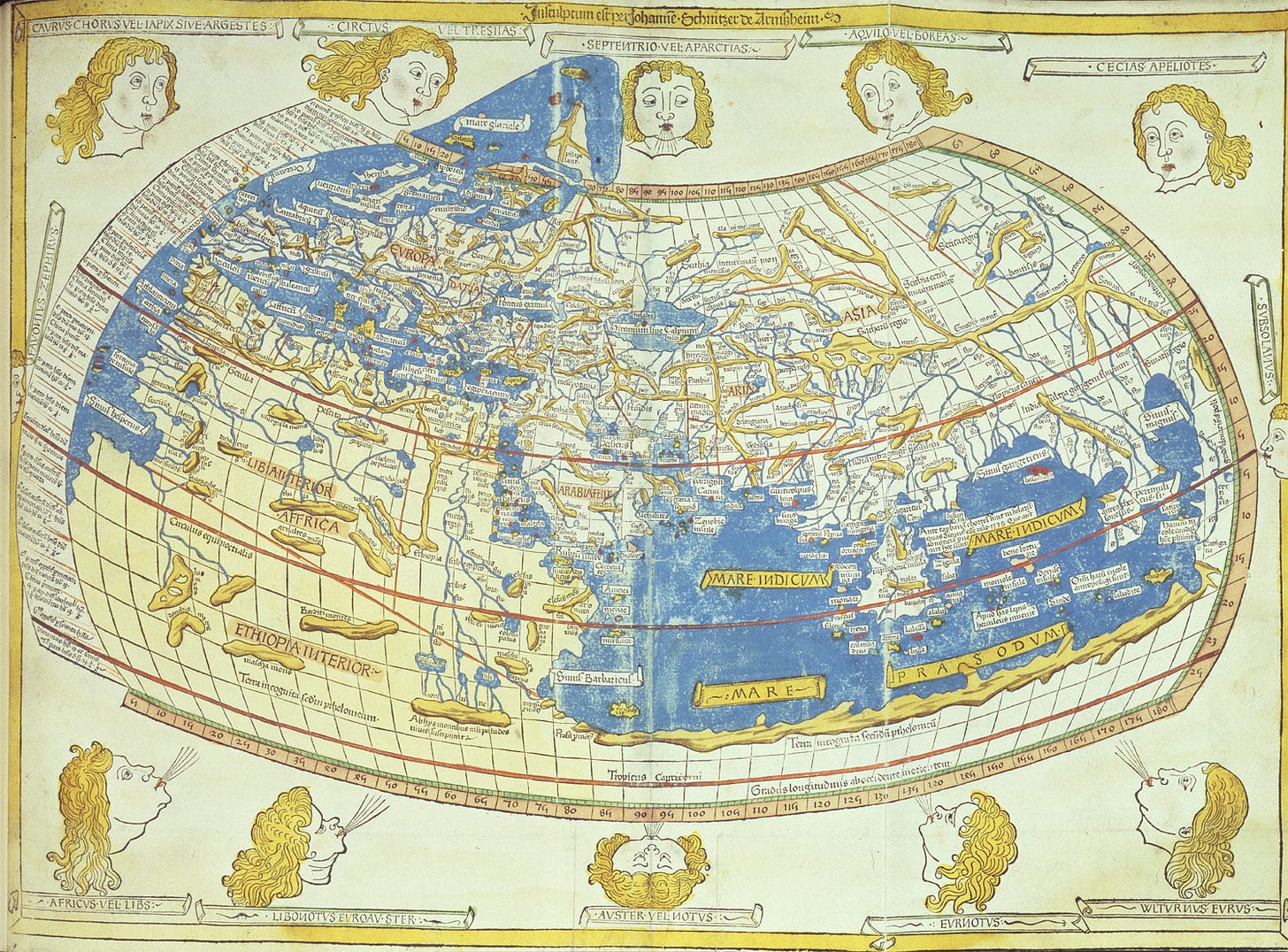

‘India’ in the Greek and Latin imagination was a term for a region to the east, beyond high mountains and the sea. It was both fantastical and real. Its limits were unclear, especially to the south and east. Did it join up to the bottom of Africa and form a single continent, enclosing the Erythraean Sea or was it separate from Africa? How did it relate to the lands even further East?

On one hand, products such as pepper and gemstones came to the Mediterranean from ‘India’, proving its reality. On the other hand, it was a place of uncertainty and speculation, as foreign and distant from Strabo in Amasya or our scribe in Constantinople as the first or the ninth century are from us.

How did the world of the Mediterranean fit together with the world of the Western Indian Ocean? How was it possible to know about places far away and the people who lived in them? What did people mean when they talked about ‘India’ and how did that match up to South Asia itself?

In a sketch map in the margins of a manuscript, we can see two people a thousand years apart, asking these questions. It still gives me a shivery feeling to think that Strabo and the scribe would understand, if I could explain to them, that a thousand years later still, I’m asking those same questions, too.