Telling a good tale

Ötzi, the limits of knowledge, and the inexorable appeal of a murder mystery

Greetings,

Happy Friday! It is high summer here in Yorkshire and I’m still wearing a cardigan as I type this. Still, as some people like to say (in Norway, I believe), there’s no such thing as cold weather, just improper clothing. And in 1991, walkers in the Alps were shocked to find what would turn out to be proof that people have known this for a very long time.

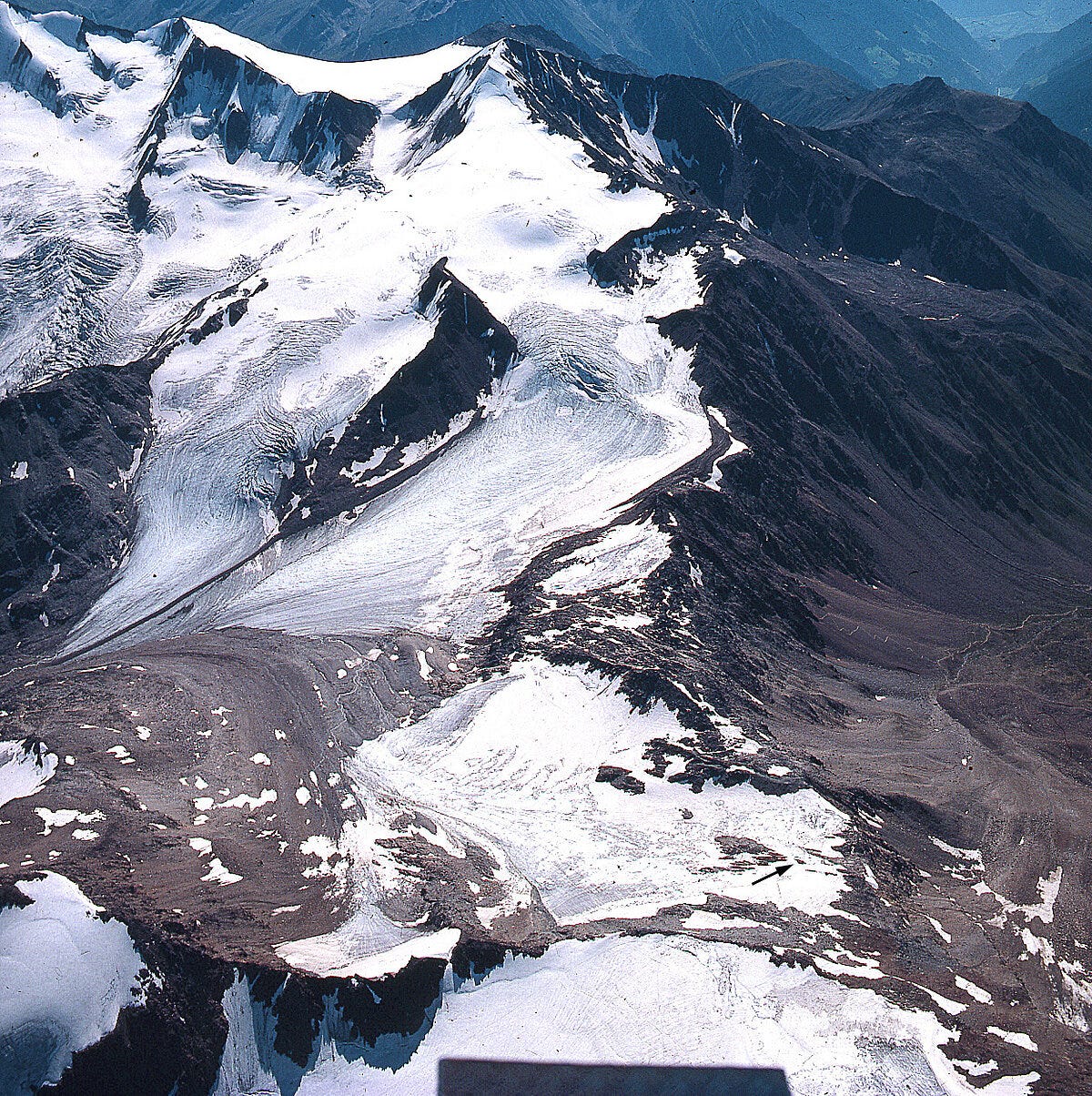

A couple out hiking caught sight of human remains protruding from ice, high up in the mountains between Italy and Austria. At first, nobody knew who it was: it could have been a missing person, recently lost in the hills. Soon the clues started stacking up that whoever it was had been there quite a while. We now know that the man, known as Ötzi because he was found above an Alpine valley now called Ötztal, died around 3230 BCE. He had, in fact, been there for around five and half thousand years.

I was excited last month to visit the South Tyrol Archaeological Museum (which is really the Ötzi Museum: the displays about him have expanded so much that the decision was made not to try to fit anything else in there). When Ötzi was discovered I was 6 and TV programmes about him are some of my earliest memories of thinking about deep history. Throughout my childhood it felt like every few years there would be a new documentary along the lines of ‘New Discoveries about the Iceman’. It was a bit like going to meet a celebrity.

I’ve written about my feelings on the display of human remains, so I was pleased that the museum offers the option not to see the man himself, while still seeing all of his gear. Whether you opt to see Ötzi himself or not, it is completely fascinating.

A very short introduction to… Ötzi the Iceman

There are lots of places where you can find out all about Ötzi: how he was found, the many tests that have been performed on him, incuding the food in his stomach (and the parasites), and even the legal-diplomatic wrangling over which side of the Italian-Austrian border he was found on. (He was on the Italian side, but so close to the line that conspiracy theories bubble on that he was really ‘kidnapped’ from Austria.) So I’ll confine myself to an incredibly brief overview.

The man (whose real name we obviously have no idea of) was aged around 45 when he died. He was killed by an arrow shot into his shoulder, probably from around 20m away, which he could not have survived for very long after he was shot. He also had a defensive wound on one of his palms, made at around the time of his death.

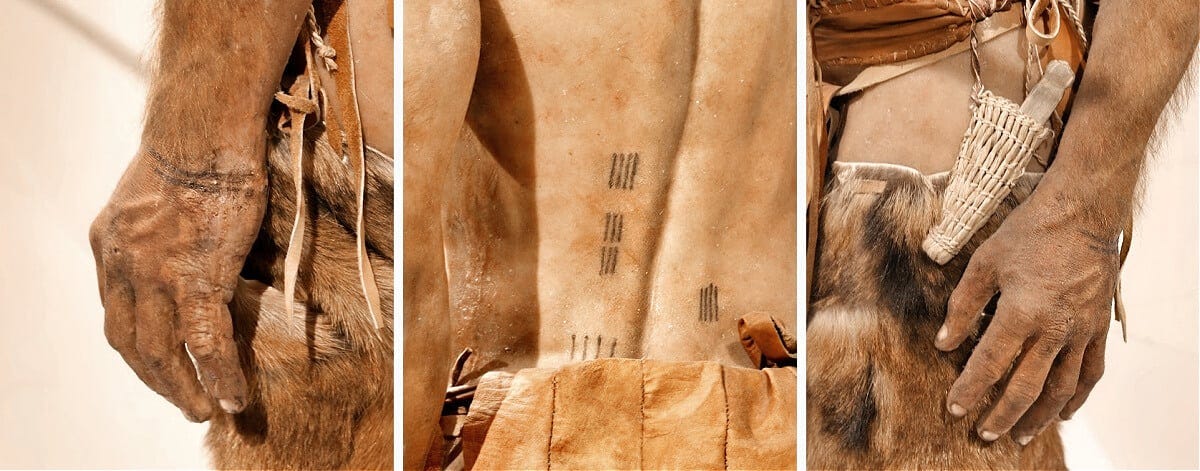

Although he died in early summer, he was dressed for travel in the year-round ice and snow of high altitude. Among his belongings were a longbow, bowstring and arrows, all partially made. He also had a knife, warm clothing, ingenious shoes made from wooden frames stuffed with moss, which would keep feet toasty warm and give grip on slippery surfaces. The moss could also regularly be re-stuffed to keep them dry. He was wearing a bearskin hat and goatskin leggings, sewn to give a striped effect, using light and dark coloured hides, a loin cloth and a long jacket or waistcoat, also made of hide.

Among his possessions were a firelighter. This consisted of a lump of rock containing iron pyrites, which could produce sparks when hit with other stones, as well as a clump of a particular type of moss that works very well as tinder. There was also a birch-bark container holding hot embers wrapped in fresh, wet leaves. These were partially burned through, showing that the container was in use: he would have needed to stop and re-wrap the embers every few hours to stop them incinerating their packaging. Still, carrying embers like this would have made life much easier at high altitudes, where low oxygen levels make lighting a fire from scratch very difficult.

Perhaps his most unusual possession was a bronze axe. The bronze came from the region of modern Tuscany, so much further south than anywhere he had ever lived. This axe actually pushed back the timeline on when people began working bronze in central and northern Italy by around a thousand years. It would probably have been traded further north to where Ötzi and his people lived. It would have been an extremely unusual and striking object in a culture that mostly used stone tools, like the arrowheads and dagger that Ötzi carried.

Because of the amazing state of preservation of his body, scientists have been able to do all kinds of tests on Ötzi. We know, for example, that he spent most of his life living further east on the southern side of the Alps than where he died, but he had moved westwards a handful of years before his death. He also had arthritis in various joints, including his lower back, hips and wrists. Tattoos, mostly in the form of parallel lines, arranged either horizontally or vertically, cluster on these parts of his body. They may have been partially therapeutic, perhaps using a similar logic to acupuncture or Reiki, that pressure or punctures in specific parts of the body can relieve pain or reduce inflamation.

Taking part

One of the most fun pieces of display in the South Tyrol Archaelogical Museum is incredibly simple. Alongside all the scientific test results and sophisticated re4constructions, there is a table with paper and pencils, a black pinboard and an invitation to submit your own best guess at what happened to Ötzi. Based on the handwriting, adults and children alike have given it their best shot. The answers ranged from the simple (and unnlikely) to the laconically philosophical. My favourites included:

He must have been carrying something valuable that people wanted. (Simple, but unnlikely because Ötzi was found with several valuable and portable objects. In fact, it is hard to imagine anything more valuable in the world that Ötzi inhabited than his bronze axehead, yet it wasn’t taken.)

People are just like that, aren’t they? (Philosophical, but I was left wondering what the world had done to the writer. It probably wasn’t a flint arrow to the shoulderblade from 20 metres away...)

From the look of the board, the museum gets enough material to switch out the display quite often. My handwriting isn’t a kindness to others, so I didn’t pitch my theory there and then, but that doesn’t mean I could ignore the challenge, so here goes…

A story that fits

He was a mature man, probably among the older people in his world but, apart from some arthritis, he was still apparently pretty fit: he was up in the mountains, dressed to make the high Alpine crossing and carrying a yew bow taller than he was. There are lots of different theories about exactly how the bow might have been intended to be finished but most of them agree that it would have had a draw weight of at least 50lb (or 22kg).

He was well dressed and not just in terms of the practicalities of mountain travel. His striped leggings and bearskin cap look like carefully made, stylish choices. The cap, especially, might have been meant to signal (or imply) that he had killed a bear himself, one of the fiercest predators in those mountains, then and now. The bronze axe also seems like something unusual.

Specially chosen materials in his kit, such as his fire-lighter and well-made shoes, as well as the embers, carried from his last campsite, all show that he was well prepared for a long mountain journey, yet his bow and arrows were not finished.

There are lots of theories. One of the most popular is that he was ‘a man on the run’, being pursued, perhaps for theft, but does this really fit? One way of thinking about this is to work our way through the facts we have as a set of choices or events that we can see our man making. To me, they don’t feel like a Neolithic ‘police chase’.

It seems clear that he was planning to travel over the mountain pass: it wasn’t a last-minute decision. He didn’t run away into the mountains on a whim (or because he suddenly realised somebody was after him). Almost everything he was carrying was designed for being up in the high passes, but would not have been necessary in early summer in the lowlands and, if you were running for your life, would you bother picking up a half-finished bow and arrows?

He was probably a man of status, perhaps a respected elder or group leader. We don’t know anything about how his people organised themselves - his role might have been elected, selected or hereditary, advisory or authoritarian. But parallels from other, modern societies with similar numbers of people, who hunt and gather food show that it isn’t unusual for older individuals to be valued for their knowledge and wisdom. Archaeologists who know this period much better than I do are confident that the axe would have been a highly unusual object, perhaps emphasising that he was an important person.

The body was found alone but we have no good reason to think that he died that way. It was a remarkable series of coincidences that preserved this body. He fell into a small hollow where the snow and ice rarely melted, he was not found by animals, etc., etc. If other people were with him, first they may not have died but, even if they had, they probably would not have lain there to be found for more than five thousand years.

High up in the mountains, our man was shot in the back from around 20 metres away with a flint-headed arrow. He would then have had a few minutes to move around before he lost so much blood that he lost consciousness. It looks as if he ran off the ‘path’ (or the simplest route across where he was travelling) before falling on his face in the natural dip, which, as we’ve seen, protected his body and clothing. Presumably, it also hid him from whoever had shot him. But he had already been wounded on the hand, probably from putting his hand up to defend hismelf from a knife blow. It is possible that somebody had a go at stabbing him, botched it, then shot him. In fact, I vividly remember a reconstruction of exactly that in one of those TV shows I saw when I was younger, but it is just as possible that he was wounded by multiple assailants.

As far as we can tell, nothing was taken from his body, including some very portable and unusual objects. Nor was his body mutilated or interfered with. If he had been travelling alone, a thief on the run being hunted down, it surely would have been pretty easy for the person following him to track him to where he fell, or just take a good look around for him. Then we might expect them to have taken whatever they could from the body or, if he had done something really awful, to have taken the body or some proof of death (like his head!) away.

Based on all of this, I don’t think our man was travelling alone. Instead, it makes more sense to me that he was with a group and was probably attacked by another group. In the chaos of people running, fighting and shooting arrows, he could have been wounded in his hand then felt the shot in his back and run off into the rocks.

It also seems to me that Ötzi’s side didn’t win, or at least didn’t win outright, because if they had they might have gone back to look for him. The other side may not have known or cared much about him personally if this was a group-on-group skirmish. Or they may also have suffered losses in the fight and both sides retreated, leaving behind their dead, with only one still lying where he fell thousands of years later.

So where does this leave us? How about a leader of a people who, after many years living further to the east of the Italian side of the Alps, had to move west. Maybe they were driven out by population pressures or a fight over something else. They spent a couple of years below the mountains where Ötzi was found. Perhaps they thought they were safe again or perhaps it was a stressful time, always under threat from others encroaching on their hunting grounds or hurting and harrassing grouop members when they found them out foraging. That might be why Ötzi was such a valued leader, with his axe and his bow and his cap that perhaps proclaimed him to be a killer of bears.

Eventually, the pressure was too much. Did something happen? An attack or a threat? Or did they just get tired of living with a constant threat? Whatever the reason, they packed for the long, cold trek across the mountains, hoping to find somewhere safe and peaceful on the other side. They left in early summer, even though, a few weeks later, the crossing would have been easier. Maybe that is why the bow and arrows weren’t finished. Ötzi could have been making them ready for a summer crossing but then they had to leave sooner, but still with time to pack properly, and with plans to need a bow and arrows on the other side.

Did they gather moss for their mountain shoes full of hope about good country they had heard of on the far side of the high peaks? Or did they set off into the unknown, simply hoping that wherever they were going would be better than here, that they could just get far enough from people who threatened them?

Whatever the case, they didn’t move fast enough. Ambush seems likely. The group had had time to make a camp and light fires, from which Ötzi took his embers. He was expecting to be able to stop every few hours to wrap them in fresh green leaves. They may have been escaping but they weren’t running flat out. Then, the first arrow flew, shouts rang out. Ötzi was wounded, then shot. He ran and fell and there he stayed.

Tall tales

That is my best account of the facts as we have. Anything further and we’re drifting into the spaces between history and fiction and myth, speculation starting to create the outlines of possible stories.

Did Ötzi’s group, the ones who still could, run off higher into the mountains? Their attackers, some of them injured, might have decided that it was enough for them to have seen rivals off their territory, time to limp home and tell a triumphant story.

As they climbed higher still and the air got colder and thinner, perhaps Ötzi’s group members who had survived found each other. Did they whisper at first, still full of fear, about who knew what? Did anybody see what happened to my brother, my daughter, my son? Did everyone in the group carry embers or was that something assigned only to a leader like Ötzi? What worries did they share when they realised that he wasn’t coming back?

Perhaps they never made it out of the mountains. Groups may not have been very big: maybe 30-50 individuals. With some of their strongest members gone, it may have been the end. But perhaps they did. Maybe the survivors stumbled down from the Alps, into what are now the meadows and valleys of Austria. Embers were touched to fresh wood, a new home and a fresh hearth.

Now, perhaps, the stories began: the mighty elder, still strong despite his years, slayer of bears, warrior of the shining axe, who had led them from their original homeland and then again on their great escape over the wall of rock. Did you hear that he protected my mother with his upraised hand? How he hung behind, swinging his axe, giving the rest of us a head start. somebody said they saw him turn, beginning to head up the hill to join us, when he stumbled, an arrow in his back. Another said they saw him, when he realised he was badly hurt, running off the path, shouting to lure the enemy away. That was the last anybody knew. He became a memory, his body and his belongings part of everything they had left behind.

We are way beyond the limits of knowledge now, but by the time people started writing down stories, many, many centuries later, stories like this were already myths and legends: of great warriors and leaders, fallen in battles fought at the dawn of time, who carried fierce and rare weapons, often from far away, and wore trophies of their feats of arms.

I’m not suggesting that the ancient Greek Herakles (Hercules in Latin), with his lion skin over his arm and his huge club, used to help him destroy the Nemean lion, is some distant memory of Ötzi. But I do think that stories like the tale of Herakles probably came from events far back in group memories, as well as from pure imagination.

Maybe Ötzi’s end was nothing like the way I imagine it (especially once I get beyond reasoning directly from the evidence). But, after all, we keep the man in a fridge and pore over his parasites and delve into his blood and bones. We’ve speculated on television that he was a thief, a traitor or a lonely reject wandering in the mountains. Whatever really happened, he seems to be that rarest of rare discoveries: a person whose story remains to us purely by chance but who was, nevertheless, probably unusual in his own world. So, with all the information we can currently get, what’s wrong with telling him a good story?