Hello and welcome back,

Pull up a chair, grab a coffee. This week is all about liquid!

If you’re a UK reader, you’re probably used to seeing water in the news. Water companies need better infrastructure, people have to stop dropping weird things into their loos, rivers should to be cleaner and people would really like to be able to paddle on clean beaches. And that’s before you get to the British hobby of talking about how much water has fallen from the sky today and how much might tomorrow!

If you’re reading somewhere else, I bet that water - too much of it, too little of it, in the wrong place, or in the wrong conditon - is part of the social conversation, too.

Water is one of the essentials of life and a bringer of death. Throughout history, people have been aware of the dangers of bad water. Millennia before germ theory, poisoning wells was a tactic feared and used in times of war and people knew and feared floods. It isn’t only the Judaeo-Christian tradition that has a legend of a great deluge changing the shape or direction of ancient history.

Cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia, telling tales of the hero Gilgamesh, also speak of a great flood, which may have inspired the narrative of Noah and the arc. In Tamil Nadu, in South India, there is a legend of a great Tamil kingdom stretching out across what is now the Eastern Indian Ocean, that was destroyed when the waters rose.

On the flip side, the comparisons of God, happiness, enlightenment or love to ‘sweet water’ or ‘clear water’ are also found across many cultures. So are projects to direct and store water. That much is just practical, perhaps. If we need water and the plants and animals we rely on for food and power need water, and water can be scarce or not necessarily where we want it, why wouldn’t different socities throughout history and all over the world have tried to keep it where they wanted it and directed it away from where they didn’t?

Fair point.

But when does doing what is needed (in this case, making sure that there is enough water but not too much) reveal more about people’s worldviews and ideas of the past, present and future?

I’ve spoken before here about how much I love drains and sluices and pipes on archaeological sites.

Perhaps some of that fascination goes back to growing up in the West Midlands, a part of England not especially famous for its medieval or ancient heritage (though there are some lovely exceptions). What it does have, though, are masterpieces of the industrial age. We would go for walks along canals, with their complicated locks for raising and lowering boats and huge steel aqueducts. And when I was quite small, I remember being taken here:

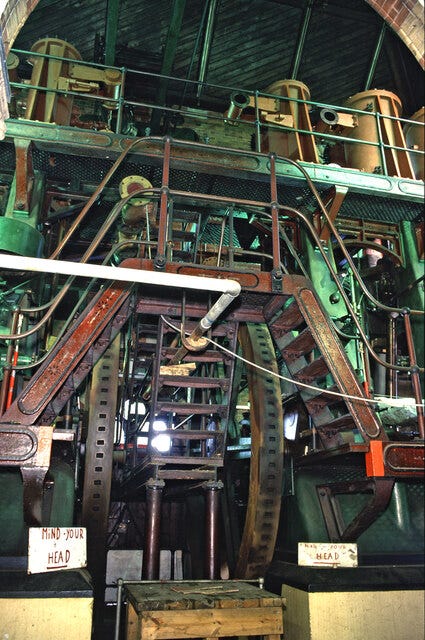

This is Bratch Pumping Station. It was built between 1895 and 1896 as a result of a dispute over water prices between Wolverhampton and the smaller neighbouring town of Bilston. The occasiona for our visit was special: it was a running day for the two mighty vertical steam engines, named Victoria and Alexandra. They were supplied with coal from the nearby Staffordshire and Worcestershire canal and I can remember walking around the huge building, up onto narrow wooden gantries, and looking down on the moving machinery.

The noise was incredible. The power was a little frightening and completely exhilerating. The other thing I remember vividly, though, was the light. This was not the dark of an engine room. The windows are high and large. The face consciously mimics the architecture of Venice and the Gothic cathedrals of western Europe.

Sure, this was Victorian industrial Britain: eclecticism was in, whether you were talking architectutre, interior design, jewellery or anything else that could be elaborated upon. Lots of urban churches look a bit Venetian and Gothic, too. Nevertheless, even if the specific styles changed, religious buildings had generally always been fancy in Britain. Pumping stations, though, had no precedent. They were new, part of the possibilities that industrial technology was bringing to the towns and cities of the country. So I think it is interesting that these places were sanctified by the old: they were made important by looking like things that already were. And it wasn’t just Bratch Pumping Station.

Even closer to where I grew up was a building that enchanted me as a child. It was already derelict but I would imagine doing it up, the details of my picture growing year by year. Goldthorn Hill Pumping Station was built in 1851 and, as you can see, the style here is more ancient than medieval, with colums on the corners and flat roof like an ancient Greek temple and still those huge windows, flooding the engines that would once have been inside with light.

Perhaps the most famous of these celebrations of the domestication of the power of water is (obviously!) in London. Crossness Pumping Station has become a tourist attraction in recent years and its exuberant architecture is more like an Orthodox church in style than any other utility building I know of. It is now a museum (and wedding venue!) and you can find out more here.

The currents of history

On my first trip to Istanbul, many years later, I saw a very different architectural masterpiece dedicated to water. Beneath the old centre is a tourist attraction that can be all too easy to miss. In fact, until recent centuries is was largely filled with rubble and was always meant to be invisible to people passing by on the streets above it.

Now, it is known as ‘the Basilica Cistern’, though we don’t know if it ever had a fancy name when it was made.

‘Basilica’ and ‘cistern’ are not necessarily everyday vocabulary if you’re not an architectural historian or an archaeologist. To add to the confucion, at least in the UK, cistern in day-to-day usage generally means the part of a toilet that holds water ready to be flushed, so what on Earth is the Basilica Cistern?

Well, the toilet reference here is neither gratuitous nor completely misleading. A cistern is a tank for storing water, hence its application to indoor plumbing. In arid areas all over the world or places with water supply problems for other reasons, though, cisterns were (and are!) often much larger. They are used to catch and store rainwater.

In Venice, for example, the whole city is surrounded by the salty lagoon. Consequently, almost every large building and campo (or square) sits on top of clay-lined storage pits. Often you will see that the paving slabs in courtyards and squares slope slightly towards the four corners of the space, where stone drain covers allow water into the cistern. A wellhead in the middle gave access the water.

In Constantinople in the sixth century, when the Basilica Cistern was built, the same strategy was used. There are fresh water sources that run into the city, including both a river (now pretty much disappeared) and a large aqueduct network but it was an enormous city. Population estimates for this period range from 100,000-250,000 with ease. And that meant a lot of water consumption. In the richest area, right around the imperial palace, the Great Church and the hippodrome (horse-racing arena), consumption would have been at its highest. Think bath houses, ornamental fountains, including to provide drinking water for the tens of thousands of people coming to see the chariot races, plus thousands of servants, courtiers, horses and hunting dogs needing to drink, fancy clothes being laundered, washing up from mega state banquets… Then, as now, the rich consumed more than the poor. In fact, how much a person consumes is one usable measure of wealth and poverty.

The ‘cistern’ part, then, was about creating a space to store rain water for these many uses.

‘Basilica’ is a word for a kind of building in the Roman Empire and for buildings built in that shape since then. Originally, it was a room designed for law and government. Effectively, it was a big audience chamber and its name is related to the Greek word for ‘king’ (basileus). It had a raised stage at the front of the building, where the king (or magistrate or whoever) would sit, often in a curved space with a big window (an apse), so that the person on the stage would be dramatically bathed in light. In front of this stage was a wide open, rectangular space with a large doorway at the other end, so that people could come in, immediately see the most important person up on the stage, then have space to walk towards them, often down a wide aisle, or to sit or stand somewhere to the sides but still be able to see and hear what was happening at the front. Being able to fit in a lot of people like this was handy for all sorts of things like giving legal judgements or making speeches. And to hold the ceiling up in a very large, rectangular room while still letting everybody have a view of the front, basilicas are held up by columns.

Now, if this sounds a bit like a lot of churches you may have been into, especially in western Europe, well spotted! When Christianity became legal in the Roman Empire in the 4th century CE, Christians borrowed this style of building. In fact, in many cases, they appropriated the buildings themselves! The style worked well for church services. A large congregation can gather in the open hall, with a view of the stage (often called a bema when it is in a church). There the priest can deliver sermons and perform the mass at the altar and those big windows flooding in light fit with Christian ideas about Jesus as the light of the world. You can also have processions down the middle aisle, whether it is the choir for a carol service or the bride at a wedding. Not all churches are built in this style, but the majority still are.

What gives the Basilica Cistern its name is the impression created by those rows and rows of columns, a bit like walking into a basilica-style church. The columns were recycled from older buildings but have clearly been installed with care for their appearance.

Like the Victorian pumping stations I started with, this was a building designed around access to water but also to be beautiful. In 2014 I was also invited to speak about the Basilica Cistern on a podcast for a wonderful project by Roma Agrawal on amazing buildings. If you want to know more, I really recommend the book that went with the series:

Agrawal, Roma, BUILT: The Hidden Stories behind Our Structures. (BLOOMSBURY, 2019)

Still, I don’t think at that point I had fully joined up Bratch Pumping Station and the Basilica Cistern as a coherent idea in my mind. That took another step.

Divine symmetry

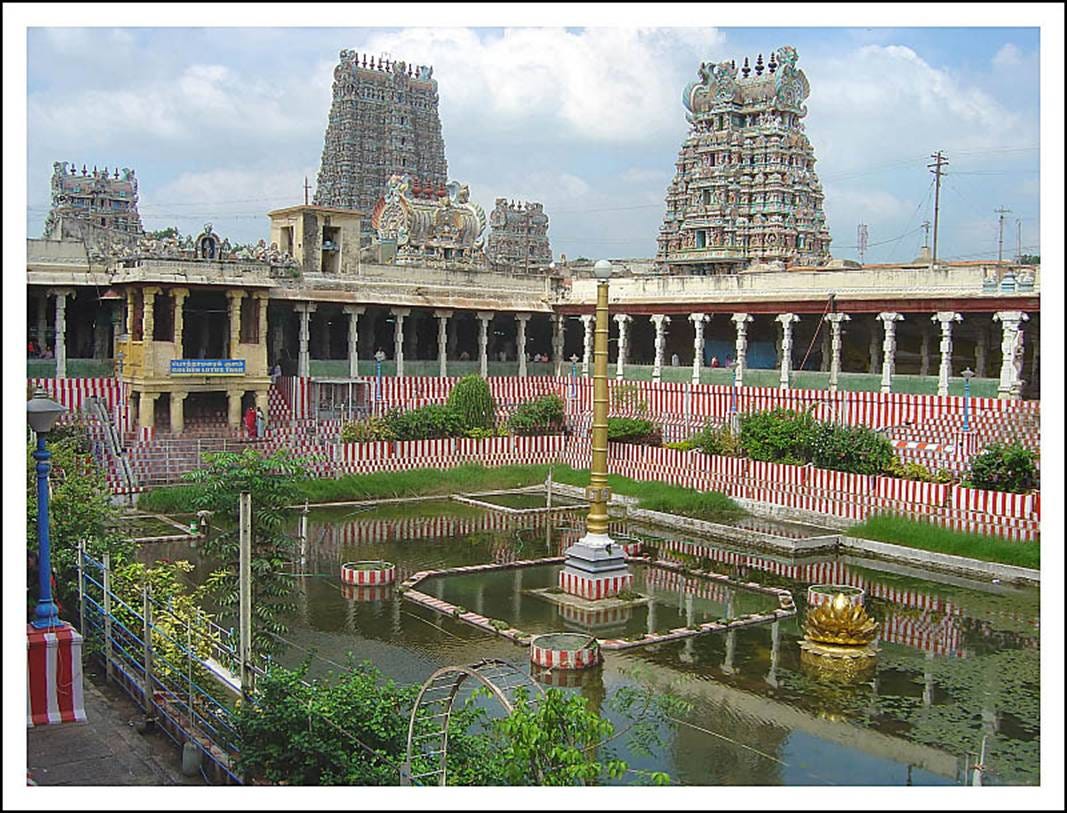

Or, perhaps, many steps, arranged in perfect symmetry. The first time I remember consciously seeing a step well in South India was at the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai. It is really the towers of the Meenakshi temple, built in the 11th-12th centuries, that steal the show but the tank in the heart of the temple is carefully designed with aesthetics and functionality in mind and it is part of a tradition across South Asia which has reached some striking levels of elaboration.

Step wells are a response to local conditions and climate. In particular, the open style can catch huge amounts of water during the monsoon. Covered cisterns with drain covers couldn’t capture that volume of water quickly enough. With open tanks, though, there is a lot of loss to evaporation. As a result, the water level fluctuates dramatically over the course of the year, from one monsoon to the next, hence the steps. They mean that people can access the water at whatever level it is at.

Step wells are also often designed to take advantage of a major benefit of evaporation: localised cooling. With seating areas and platforms, people could use them as social spaces. They are also used for bathing and swimming.

Like the examples of water management we’ve already seen, their physical form also has a strongly spiritual dimension. Take the Ran-ki-Vav stepwell, from Gujarat:

It was built in the 11th century by Udayamati, the wife of a Chalukya emperor. The Chalukyas ruled a huge empire from the Deccan region of central India that doesn’t get as much press as it deserves. If you want to know more, though, I’m currently reading a vivid and beautifully written popular history about them:

Kanisetti, Anirudh, Lords of the Deccan: Southern India from the Chalukyas to the Cholas (Juggernaut Books, 2022)

What stands out so strikingly about this step well is the elaborate carving, very much in the style of temples at the time. As they rose into the air, so the carvings here sink into the ground, creating steps, walls, walkways and platforms. If you are interested in seeing more step wells of India, check them out here.

The water of life

Maybe the blending of spiritual architecture and the architecture of water shouldn’t be a shock. Without it there can be no life. Perhaps more surprising to me has become the different ways that people have done this across time and space.

For the Victorian engineers of industrial Britain the relationship between human, God, the world and technology was a very real question. Most people whose exuberant buildings still stand were religious in an environment of competing Christian denominations: what it meant to be a good Christian was a live issue. The incredible pace of technological change was seen by many as a reflection of God’s favour but people also saw and wondered at the suffering and poverty it brought. Bilston, which received its water from Bratch Pumping Station, was richer during the industrial revolution than at any other time in its history but its people worked hard in dirty, unsafe industries. Maybe that is why buildings associated with water in particular are so often a bit religious-looking: could there be a clearer ssymbol of just, godly scientific progress than bringing clean water to the people whose bent backs were pushing the world forward, as they saw it, with their blood and sweat?

The Basilica Cistern, by contrast, was built in a time and a place when the role of God in human life was nearly universally accepted and yet we don’t actually know if the Basilica Cistern looked all that much like a church to the people who built it. It is more square than rectangular. It has no wide entrance and no stage and curved apse. It has rows and rows of columns to hold up the street and its buildings above, instead of the traditional three aisles formed by two rows. The simialrity to a basilica was in the eyes of modern archaeologists when they excavated it. Still, it was clearly designed to be a beautiful space and we do know that cisterns weren’t just accessed by a bucket lowered from above: a couple of centuries after the Basilica Cistern was built, an emperor’s infant son drowned in one while playing. Tragic and surprising as this must have been, it clearly shows that cisterns were not just invisible underground spaces.

The critical factor here might be the way that, for the Byzantines, the world below was an imperfect mirror of heaven above. The imperial court was viewed as a reflection of the court in Heaven, for example, with the emperor and Jesus in analogous roles. Whether the Basilica Cistern was directly modelled on a church or not, it represented the duty of a Christian emperor to provide facilities like water and it expressed a belief that the beauty and physical order of the built world reflected a striving after the perfection of God’s creation of the world.

In the case of the step wells, each of them, like each of the pumping stations or cisterns, has its own unique story but they also fit a different pattern again of seeing the relationship between water, spirirt and human creation.

Bodies of water were (and are) often associated in South Asia with the habitation of divine beings. The concept of ritual or spiritual purity is also critical to many South Asian religions and spiritual practices so who got to use public water resources, when, with whom, etc. was often about expressing in the physical world the organisation of the universe dictated in spiritual terms. The use of styles that make wells look like temples is less about the world as a mirror image of a perfect heaven and more an expression of the world as a set of unique links between the spiritual and physical. Each well is specific to its own place and community. They create possibilities for life but also provided people with ways to express community dynamics through space in repeated, day-to-day ways.

Every time I travel, I try to understand more about how people all over the world have managed water because it doesn’t just tell us how people have managed to live in dry environments or crowded cities or salty lagoons. It also hints at ways that we have tried to make sense of ourselves in a world that is always a combination of what our bodies need, our senses tell us and our hearts and minds believe.