One thing most of us learned in school, if we studied history, was that sources come in two main flavours:

primary sources

secondary sources

But what makes primary sources primary and secondary sources secondary? I’ve been teaching undergraduate history for long enough to know that answering this can be a bit of a problem.

Common answers include:

Primary sources were made at the time, whereas secondary sources are made later.

Primary sources are by people who were there, whereas secondary sources are not.

Words like ‘original’, ‘eye-witness’, ‘contemporary’ and ‘older’ come up, while secondary sources are usually defined as against primary sources: they are usually whatever primary sources are not.

Let’s get specific

Things get sticky with real examples. Some seem pretty straightforward: a photo of something is usually a primary source. A diary by somebody… probably primary, too. A book about [your favourite historical topic] at [your friendly neighbourhood bookshop] is probably secondary. So is an academic article. These are all quite general statements, though.

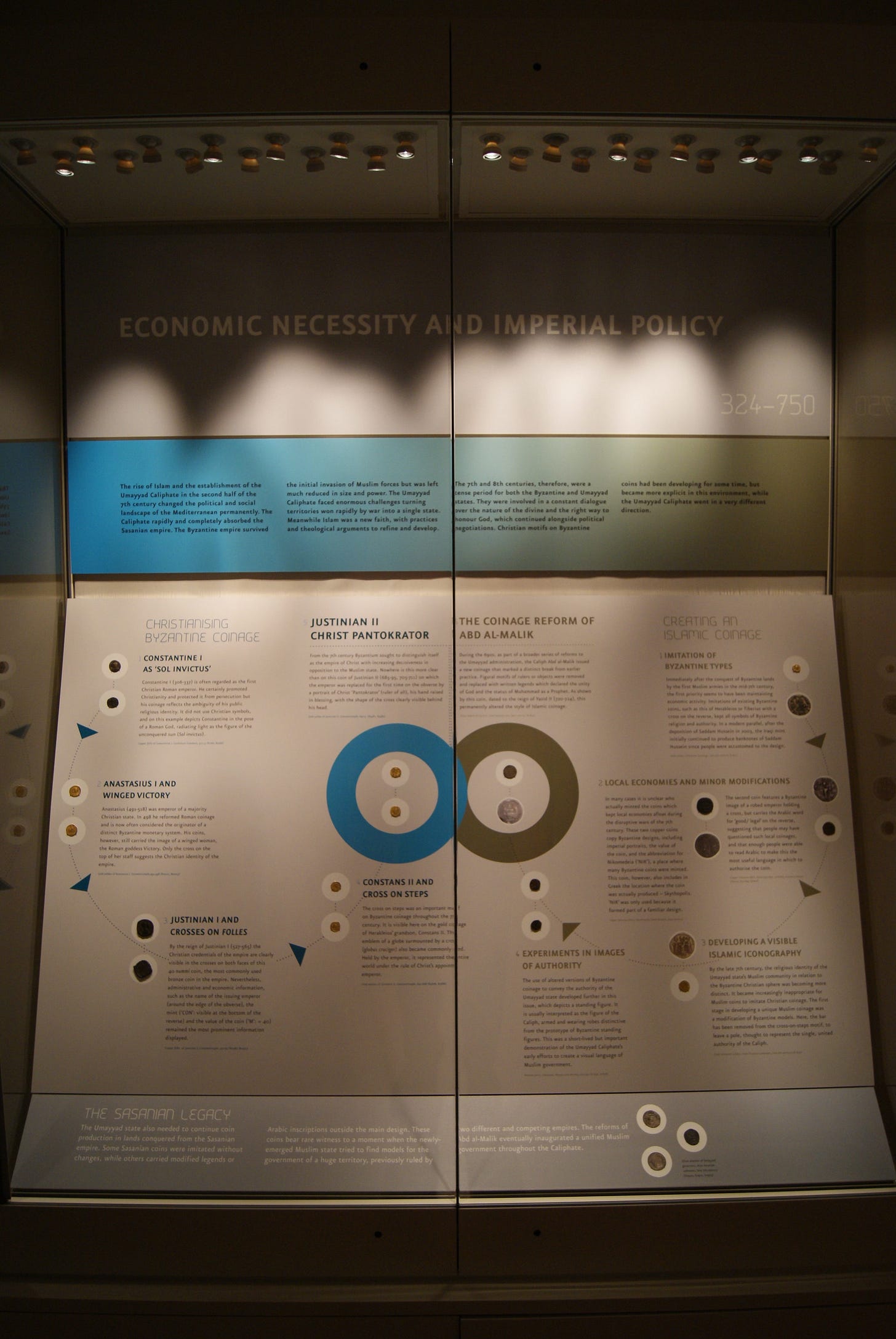

This is photograph is a picture of an exhibition that I co-curated at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham, back in 2013.

This book is the cover of R. E. M. (usually known as Mortimer) Wheeler’s popular 1952 book Rome Beyond Imperial Frontiers. Already a celebrity archaeologist (perhaps the first celebrity archaeologist: check out this 1956 clip from the popular TV show ‘Animal, Vegetable, Mineral?’), this book brought together Wheeler’s archaeological work on Roman sites from Britain to South Asia, as well as lots of published material about the Roman Empire.

So, are these primary or secondary sources?

I’m not hiding a secret answer…

I’m usually pretty sure when I ask students these sneaky, specific questions, what the answer is. If you chucked a bunch of these kinds of examples at me in comments, I’m fairly confident I’d know what I thought the answer was and why. (Though by the end of this I hope you’ll see why this wouldn’t make a good quiz show). But this is experience - sort of historian’s muscle memory. It isn’t the same as a clear answer.

In fact, if you read the many - and many pretty good - guides to studying history, you’ll find something like the things that students say: that primary sources were made at the time, that they are ‘original’, that they are by people who were present.

One problem is that the books also tend to talk generally. Another is that most (not all!) of these works are by people who study quite recent history. Modern history isn’t necessarily simpler but it doesn’t always throw up the same range of possibilities as earlier history.

Let’s take that idea that primary sources were made at the time something happened. A historian who works on the 19th century might find it pretty straightforward that sources made in the 19th century are primary while things written about the 19th century in the 20th or 21st century, especially by historians, are secondary.

As a medievalist, though, things get way messier very quickly. Take a source like Geoffrey of Monmouth, who wrote about the history of Britain in the 12th century. He pieced things together from earlier documents (many of them now lost), popular stories and whatever else he could get his hands on. He wrote about things that had happened centuries before. Primary or secondary?

…I do have a suggestion

There isn’t some ‘secret’ answer, but obviously, I think I’ve got something to add, or this would be a pretty pointless piece of writing, so let’s start with two things:

’Is this source primary or secondary?’ isn’t actually a very good question.

History is a kind of literature. It has a muse (who may or may not like coffee). It aims to be persuasive. It helps (though isn’t mandatory) if it is written enjoyably.

If we start out with history being the process of trying to understand the past then convince other people about how it happened, by presenting evidence in a compelling way, then a few things follow.

Most importantly, gathering primary and secondary sources about something always starts with the ‘something’. Even if you find a big treasure trove of random stuff (like the Cairo geniza), by the time a historian starts writing about what these random sources mean, how they fit together and what they can tell us, they’re already using the pieces as evidence for a wider ‘something’: how the stuff got there, or the world that they illuminate.

‘What is this a primary or secondary source for’, is a much better question.

Sure, some things will pretty much always end up on the ‘this is a primary source for [whatever]’ side of the line, but lots of things won’t.

Back to specifics

Thinking about those two examples: is my photograph of an exhibition a primary source for how museum exhibitions have changed over time? Hell, yes! Coins are notoriously hard to display, and people have tried all kinds of methods. Putting them on large, pre-printed story boards was something a friend and I came up with, which made the most of developments in digital design and printing. It was new and (we think) pretty awesome at showing off and making sense of some incredible material.

Is that photograph a primary source for economic policy or religious propaganda in Late Antiquity? Not in this universe. In some post-apocalyptic future, in which that photograph might be the last record of the existence of the coins, maybe. (And the apocalypse might just be the passage of time: working with some sources for the first millennium is a little bit like trying to understand Late Antique economic policy by using a photo of an exhibition of coins from the time…). But, in this world, my friend and I made a bunch of choices about what to include and how to explain and present it, and since the exhibition is now over, this photograph is what remains of that secondary account of a historical period and set of changes.

What about Mortimer Wheeler and Beyond Imperial Frontiers? Pretty obviously a secondary source for Roman history, right? Right (says historian’s muscle memory).

But 1952 was a long time ago. Wheeler was digging Roman sites in the final decades of the British Empire. He’d become famous as an archaeologist in England, digging at least one site relating to the Roman conquest of Britain, and that was why he was invited by the British government to set up an archaeological service in South Asia, during the height of World War II.

There are lots of histories that have been written and might yet be written about how the past was used in building and dismantling empires and about how the Roman Empire shaped modern empires in which Beyond Imperial Frontiers is a golden primary source.

So, one answer to the question is that everything can be either a primary or a secondary source, depending on what is being asked, but that is only halfway useful.

The echoes of the explosion

Eventually, it was my partner (also a historian and often my other brain) who gave me the best answer I’ve got, which I’m running with here.

The clue, he suggested, is really in the name: primary sources are our first sources - the things we cannot go further back than.

In my mind, there is an explosion, frozen in the moment I try to see it. Nuggets fly outwards from The Thing I want to find out about: artefacts and landscapes changed by The Thing, art and music trying to make sense of it, writing about it by people who were there and people who heard about it. Some of those first traces, exploding out from The Thing get lost over time, but copies of them, or other people reflecting on them or describing them survive. These may be centuries later, but they become the closest we can get to The Thing along that particular trajectory from it. They are still primary.

In order to figure out what The Thing was, how it happened and what it meant, the only option is to gather up as many of those primary traces as possible and try to tell the best story we can.

First among unequals

The explosion exhibits one further thing about primary sources: determining whether something is primary or secondary has no bearing on how useful, reliable or insightful something is.

Geoffrey of Monmouth is a source of last resort for lots of medieval history: if nothing else survives about something, we can’t ignore what he says, but when other material does survive, it is very clear that he was pretty mixed up and liked a dramatic tale. And this isn’t just a medievalist problem.

Eye witness accounts for events today are invaluable and notoriously difficult to work with. Imagine trying to figure out what is going on right now in one of the many conflicts around the world: do you go to a blog by one individual fighting on a front line, or an overview by a news agency working with hundreds or thousands of those accounts, as well as military and government sources, satellite photography, etc. etc.?

Like most things about history, it isn’t really about the past at all…