Recently, I had the opportunity give two lectures about the Roman Empire. Just two. It was a wonderful challenge. How to summarise something so huge? Talking about the Roman Empire is especially fun because it is so… present… Often people don’t even realise that they’re standing in its shadows.

(Sometimes, people do. Last year there was some thing on Tiktok that my students, knowing that I am not on Tiktok, eagerly told me about. The deal was that girls were meant to ask their male friends how often in an average day they thought about the Roman Empire. The ‘point’ of the exercise was to shock girls by demonstrating how often their boy friends thought about this apparently obscure topic, thereby illustrating the fundamental difference between boys and girls. I won’t dignify that ‘point’ with any further comment, but inevitably, they asked me how often I think about the Roman Empire in an average day. The answer depends what I’m working on, but somewhere between every 1 and 5 minutes. It was also reassuring that so many other people also do notice the pervasiveness of Rome all around them.)

What I decided to do with my lectures was also shaped by the itinerary of a journey I was on with my fellow travellers, and I’m quite pleased with how it all fitted together. It ended up going like this:

a close focus on Pompeii, from an everyday life perspective, and particularly focussing on the idea of buying and selling, markets and wages, money and spending.

a big overview on how the Roman Empire went from city state to one of the largest empires the world had (and, indeed, has) ever seen.

As I designed and gave them, a theme kept coming up: the Roman Empire feels… modern.

Now, as a historian, and specifically as a medievalist, I can and, I think, should (in the right circumstances) critique the concept of modernity. It has a lot of problems. And yet, even for somebody with many years’ familiarity with Roman history, which sometimes blunts that sense of surprise, there it was, again and again: oh wow, they did that too! That looks just like it does now!

So here we go, just a handful that hit me this time round:

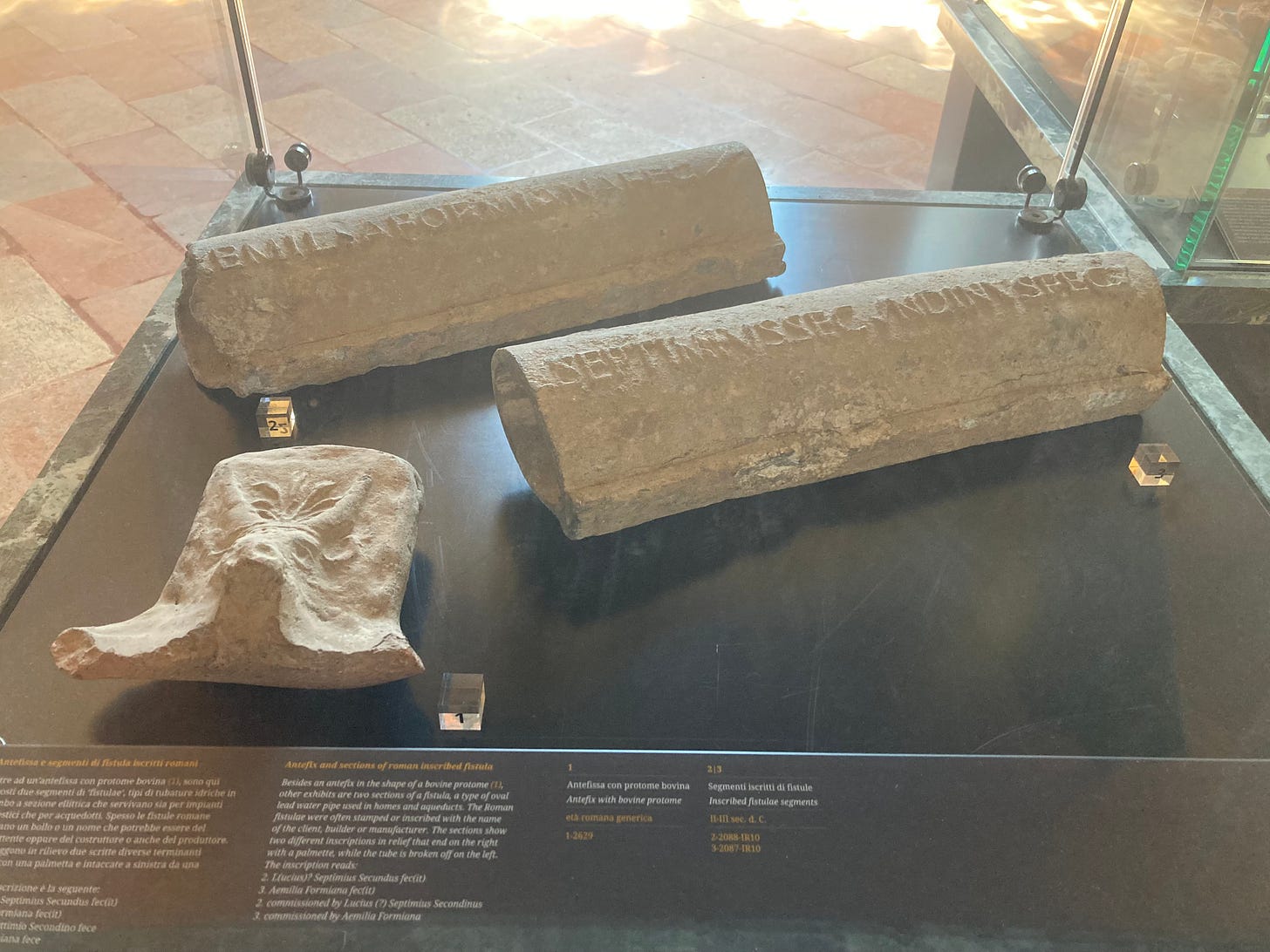

Piped water direct to multiple rooms in a house (and even branded lead pipes: you could not just get your water piped in but you could choose whose pipes you thought were best. Tradesmen could probably tell you they only use Ulpicius’s pipes because they just last longer than those others you get…)

Wallpaper: yes, it was painted on, but still… It is used as a backdrop, replicated (more or less) in one house and then the next. It isn’t art. It is something else. It is decoration.

Fashion: from hairstyles that make you cringe, and probably did the kids of the ladies who had it to geometric floors when the neighbours all had hunting scenes and animals, the Roman Empire, or at least the rich in the Roman Empire, could and did chase the latest look.

I could go on. Other people have, at various lengths and in various media, perhaps most famously in the ‘What have the Romans ever done for us’ sketch by Monty Python, which is, of course, only funny because the watching audience is either expected to know that the Romans did all of these things or to think ‘oh, wow, the Romans did that?!’

The Roman Empire was, of course, also very different from the present. Not only did it rely on mass slavery, the brutal conquest and suppression of colonised regions, the celebration of extreme bloodsport and a sharply divided class system, but it celebrated all of these things as good and righteous.

Still, it feels familiar.

One reason is because many of the shapers of ‘the modern world’ actively used the Roman Empire as their example. From architects to artists to writers and politicians, change makers from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment to the Industrial Revolution held up the Roman Empire as an example of an advanced civilisation, to be imitated and surpassed. As a result, the modern world literally looks a lot like the Roman world (see the Corn Exchange above, and try that spinning in a circle thing. The odds are less good in the US, better in Italy, but honestly decently good almost anywhere in the world thanks to subsequent European colonisation).

Another reason for familiarity is because of structural similarities between aspects of modern life and aspects of life in the Roman Empire. (In both cases, these are generalisations about what societies think of as being ‘normal’ or project as ‘normal’ rather than descriptions of what life was life for everybody.)

More people lived in cities in the first two centuries CE in the Roman Empire than would live in cities in the same areas of the Mediterranean, large parts of Europe, North Africa and West Asia until around 1900.

More people used money in more areas of everyday life than they would for more than a thousand years. (Traces of atmospheric pollution from Roman silver mining as a result of producing coinage would not be matched again until the Industrial Revolution either.)

Physical mobility, if not social mobility, was easier (sometimes even, unavoidable), more extensive and infrastructurally simpler than it would be for millennia.

And as I was writing those lectures, something important came into view, not about how the Roman Empire was like us, or even how we are a lot like the Roman Empire, but about what we often mean when we say ‘modern’.

What it means to be modern has been debated plenty, and discussed in various and insightful ways, and I’m drawing on a lot of those threads here. However, a few things that are often at the forefront of definitions of ‘modern’ have never quite rung true for me.

In particular, it is often said that the essence of being ‘modern’ is connected with industrialisation - with mass-produced goods, globalised trade routes, factories, capitalism… It is often said to be linked to long-distance and fast-paced communication - the telephone, the aeroplane, now the internet. Some people have connected modernity with advances in medical technology (especially antibiotics) which mean that people can congregate in large numbers in greater safety than they ever could before.

Yet the Roman Empire had none of these things.

Information moved no faster than a galloping horse or a ship under sail. There were some industrialised processes, even factories and definitely some capitalism, but these were marginal parts of the economy and of society. Without antibiotics, the mortality rate for urban dwellers in the Roman Empire was staggering, even by the standards we tend to attribute in a blanket way to ‘the bad old days’. (Urban life expectancy may have averaged only around 20. By contrast, it was probably 32-40 through most of the Middle Ages and in most other pre-antibiotic societies with ‘normal’ levels of disease, injury etc.)

Why, then, does Rome feel so familiar? What does it mean to say it feels modern?

Here goes my best suggestion:

The crucial things that a lot of us - enough that it can stand for a general social familiarity - recognise about the Roman Empire are the various causes and symptoms of a society with high levels of anonymity.

Bear with me: this is not some accusation of dystopia. There are bad and also very good things about anonymity (at least, from my subjective, modern perspective). There were also lots of things about the Roman Empire that were pretty dystopian, but that isn’t what I’m reaching for here.

The Roman Empire had various causes of anonymity that make it seem modern:

High concentrations of population, in big cities with major levels of inward migration. Lots of people, not necessarily in absolute terms, but enough to shape the dominant narratives of society, were not embedded in inter-generational, physically fixed communities. Many people may not have known their neighbours, or they may have formed new, temporary communities, in city blocks or inns along the thousands of kilometres of Roman roads.

High levels of population mobility, again, not necessarily at an absolute level, but it was not the largely stable, country-living peasants who made up the majority of the Roman population who shaped its presentation of itself. The people whose lives have defined how we see the Roman Empire, often but not always because they could write, moved a lot - soldiers, slaves, diplomats, traders, gladiators, travelling tutors, pilgrims, touring athletes and actors.

Scale - this is harder to summarise, but is something to do with how large the Roman Empire was and how successfully it promoted a common culture in that space. People from the Euphrates to the Humber, from the Sahara to the Danube, used the same coinage. If they were educated, they could write in the same elite language, Latin. They could enjoy baths and theatre and many of the same foods, which could be shipped around using army roads and publicly subsidised shipping, so that you could ask your relatives to send pepper to northern England to make the food more palatable. As a result, people even if they did not move around much themselves, could be and were connected to networks which put them in touch with people very far away from them. They might trade across huge distances or build relationships through letter-writing with friends even thousands of miles apart.

This, in turn, gave rise to som symptoms of anonymity, which also seem familiar:

The space to be, and record being, different. In a comparatively anonymous society, there is more space for people to live unusual lives and record them the way they choose. We may not ourselves live unusual lives, but we often see having that option as being ‘modern’. As a result, there is a weird, comfortable déjà vu about reading the tombstone of a couple who met through the army, came from Europe and Africa, each had jobs and then chose to be commemorated sitting together, with a note about a child they lost in infancy and their professional success. It isn’t necessarily that people did not live lives like this in later (or earlier) centuries, but in the first and second centuries CE in the Roman Empire, a higher proportion of people could, and they could record those lives because it was normal for people to write letters, compose their own memorials or put up inscriptions celebrating their achievements. These things tend to happen less commonly in less anonymous societies, because everybody knows everybody else anyway. Even if people were just as different, we may not see it as clearly.

The availability of similarity: in other periods and places, where there is a lower level of anonymity, where we see people investing time and money in things that were special, those things are often unique. People might treasure something hand-carved, or home-made, or, for the very rich, produced by others but only for them. In the Roman Empire, scale and anonymity made the mass expression of personal taste possible. Variations, but also extensive similarities in ‘wallpaper’ painting, jewellery, hairstyles, floor tiling are all familiar to us because we can recognise the ability to invest our time, money and energy into crafting a unique life for ourselves out of elements that are very widely available.

Communities of interest: with the bonds of family, place and stability not being as central as in other times and periods, it was possible in the Roman Empire of the first two centuries CE for people to connect because of shared interests, and indeed, for some people to earn their living out of those interests. I have absolutely no doubt that throughout the world, and across time, the ability to tell a dirty joke really well has always been valued, but it was the Roman Empire that gave us Martial, a poet who made his living out of writing books of filthy rhymes and snide poems about the absurdities of being rich or old or vain, and about how important it was for him for people to buy his books. There were enough people able to connect over an interest in how the world was shaped to give rise to networks of geographers, who compared notes and snarked about one another’s mathematical abilities. Artists could live and move by recommendation, from one patron to another.

Perhaps the most powerful allure of the Roman Empire’s strange familiarity is the sense that, if we could just find the right door, we could slip into it for a day and we would be… okay. It would be weird, surprising, exciting. We would probably not want to stay more than a day, but we could blend in. We could be anonymously there and that feels a bit like home.