Hello dear reader,

I’m writing to you this week on my way back from the Amalfi Coast. There have been Roman statues galore, the streets of Pompeii and the cobbles of Sorrento. And a blue that I can never quite keep in my memory: every time I return, it takes my breath away again.

I was here last year and wrote about many of the wonderful things Campania has to offer. But there is more to see every time I come back and this time I finally came face to face with a very special lady. Today’s title credit goes to Leonard Cohen and a line from what must be one of the most beautiful songs in the world about not pursuing a relationship (‘On the Level’) but it also seems particularly appropriate, as I hope you’ll agree, for a story of spices and incense on an ancient breeze and our changing ideas of what ought to be secret!

The ‘Lakshmi’ of Pompeii?

Here she is and isn’t she beautiful?

I was on the lookout for her from the moment I entered the National Museum of Archaeology in Naples, but never expected to find her where I did. Let’s start at the beginning though: who is she and what is she doing in Naples?

This wonderful little figure (she is quite tiny, at only about 9 1/2 inches or 24.5 cm high) was found some time between 1930 and 1938 during excavations of Pompeii and has been dubbed ‘the Lakshmi of Pompeii’ after the Hindu goddess of wealth, abundance and luck. She is not, however, Lakshmi. That label was attached to the figure by specialists in Western classical archaeology, who correctly recognised that she was South Asian in style but who did not necesarily realise that the religious and mythological imagery of South Asia is as complex and specific as that of the classical world.

For example, if you see an image of Minerva, the Roman goddess of (among other things) wisdom, justice and victory, she will almost always be wearing a helmet or other headgear with military connotations and carrying a spear. ‘Attributes’ or things that figures carry, wear or display physically, have been used since the beginning of art to help people to identify a figure. These attributes would usually allude to stories about a figure so that you would recognise the elements from the story and immediately think, ‘Oh, that must be…’.

The classical hero, Herakles/Hercules, according to myth had to perform twelve arduous labours. He is often pictures carrying or wearing a lion skin, reminding people who knew the stories of the fierce lion he had killed as one of his near-impossible tasks. He is also often shown carrying a club, which is another reference to his feats of heroism.

In the case if Minerva, the attributes are more general, but since there weren’t that many women in stories wearing military gear (and the Amazons of classical myth had their own specific ways of being depicted), that was enough.

Attributes are just as fudamental in South Asian art, even if that has not always been as well understood in Western knowledge systems. Lakshmi, for example, is usually depicted either sitting or standing on a lotus throne (i.e. a large throne shaped like a water lily), holding a lotus and wearing fine clothes.

Compare this with our figure and the differences become clear. She is easier to see in this black-and-white image, outside of her case:

The lovely lady of Pompeii has no very clear identifying attributes, which has made identifying her difficult but the fact that she is nude on her lower half as well as her chest suggests that she was associated with ideas of fertility. Her size and the smaller atendants surrounding her indicate that she is a divine figure of some sort, and schoalrs now think that she most likely represents a tree spirit associated with life and fertility, a yakshi.

An alternative hypothesis is that she is Lakshmi, but that how she was being depicted was influenced by classical Roman images of Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty and good fortune. Venus usually is shown nude - that is one of her attributes - and there was clearly sharing of images and ideas between the Roman Empire and South Asia in the first century CE. I’ll talk more about that in a moment, but it is why the figurine was in Pompeii in the first place. Personally, I find the yakshi theory more convincing, partly because I think scholars are still too quick to attribute things in Asia and Africa to the influence of the west but mainly because there is no trace of a lotus flower in the Pompeii figurine’s depiction. This is usually the most instantly recognisable attribute of Lakshmi (though other deities might also sit or stand on a lotus throne). Plus, if you were making an image of Lakshmi that was already diverting from the usual design, for example by being naked, I would expect an artist to be even more careful about giving the viewer some other clue (like a lotus) about who they were looking at.

Where did she come from?

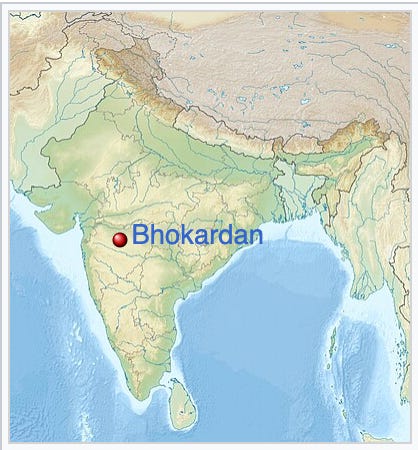

Our figure, then, is probably a yakshi or tree spirit, carved definitely in South Asia and possibly in or near Bhokardan, a city in modern Maharashtra in India. It is an ancient city and in the first century CE would have been ruled mostly by the Satavahana Empire. This was a large, powerful state and one that we know was in regular trading contact with the Roman Empire.

Bhokardan has been suggested as a possible place of production because 1) it is a very ancient city and 2) some figurines with a very similar style and design have been found there. Another possibility is that she was made further north in what is now Pakistan or Afghanistan. It is really impossible to know because the Satavahanas also traded with these northern areas, so she could have been made in and traded from the Satavahana Empire or brought there by trade then shipped westwards. We have no way to tell how common figures like this were or how widely they were made. It is most likely though that she at least departed for the Roman Empire from somewhere in the Satavahana Empire.

The house she was found inside in Pompeii is believed to have belonged to a rich merchant and certainly pepper, other spices and incense from the Indian Ocean region would have been available to buy in the markets of Pompeii before its destruction. It was a prosperous, well-connected Roman city and goods from what the Romans called India were all the rage in the 1st century CE. That isn’t the only part of the story of our figure that is interesting though.

The Secret Museum

I wasn’t expecting to see her where I did, in the first place because I hadn’t done my homework. It isn’t hidden knowledge, but I knew she was there somewhere in the museum in Naples so I was happy to keep a look out and only resort to checking on my phone if I didn’t come across her. In the second place, I had underestimated the influence of much more recent cultural forces.

At the back of the National Archaeological Museum in Naples is something that has come to be known as ‘the Secret Museum’. What, you may wonder, could that be?

The answer has varied over time: it referred originally to a collection, rather than a specific space in the museum and for over a century, since the mid 19th century, it was an awkward compromise between the public morals of the day, in Europe generally and in Catholic southern Italy specifically, and more universal human fascinations.

When excavators in Pompeii began to uncover erotic and, indeed, explicit images, as well as statues and models of genitalia and various sex acts, there was some uncertainty about what to do with them. There was a general belief at the time that such sights could corrupt the morals of people then living in a society much more buttoned down about such things. But they were ancient - Roman no less. They could hardly be destroyed and there was a case to be made that they might be valuable for understanding the Roman Empire better (which is something Europe has been obsessed with since… the Romans..?).

As a result, the secret museum emerged. Sometimes authorities would decide it must be closed and so nobody would be allowed to see the items. Sometimes it might be available… for a fee… to men… of mature mind and upstanding morals (i.e. wealthy, educated and middle aged). Believe it or not, this continued until the 1960s and the collection was not made fully available to the public until 2000. The Secret Museum (Gabinetto Segreto) now occupies its own rooms at the rear of the museum. It is a testament to many intersecting things.

First is the history of Europe’s modern and conflicted attitudes towards sex and nudity and how recently they began to change. It now seems a little silly, albeit delightful, to have a ‘Secret Museum’ at the back of a perfectly public museum, where tour guides try to elicit a bit of a titter or a gasp from museum goers who have almost certainly all seen ‘worse’. Yet public morality has not gone away as a topic of debate and likely never will. Societies are built on shared ideas of what is and isn’t okay and the fact that other societies’ rules and norms can look silly from outside is only because we tend to take our own for granted.

The second thing the Secret Museum reveals is that complex sociology of what is acceptable and what is not: what is erotic, or indeed, explicit or ‘dirty’ and what is ‘art’? A nude Venus could happily sit in the main galleries of the museum, and museums all over Europe, without anybody worrying much about her corrupting the morals of the young, female, poor or uneducated. A statue of a fawn (a mythological half human, half deer/goat figure from ancient mythology) penetrating a female goat, which looks at him with something ambivalently placed between horror and excitement? Perhaps not. It seems likely that that statue wasn’t designed in Roman times either to sit innocuously in somebody’s entrance hall!

Finally, there is that question I’ve already alluded to of what other people’s norms look like from outside and that is probably why I was surprised to find the yakshi of Pompeii in the Secret Museum. Sure, she has bare breasts. Yes, her labia are visible. But having looked at a lot of South Asian art, especially from the early first millennium CE, I didn’t see those things as erotic. It didn’t really occur to me that somebody would. But somebody did.

I don’t think, if she were excavated now, the yakshi of Pompeii would wind up in the Secret Museum. We have different attitudes to nudity, sex, art and history. We also know more about other cultures and their historical view of these things. But would I move her, if I could?

It is a difficult question. Given that our own attitudes to sex have not moved completely beyond the titters and giggles, it does seem a shame that, after all of these centuries, she’s tucked into a corner of a cabinet surrounded by pictures that the Romans probably also meant as a bit of a challenge to the polite everyday, but where she is is also part of its own story and, as a historian, I would rather keep the stories than forget them!