One of the things travellers to places like Italy often comment on is how much history there is… just lying around. I’ve felt it, too, and written about it here: those places where the past piles up and you feel yourself walking in places where people have lived and left a trace of themselves for millennia. What is it though, that creates that feeling and why does it matter?

A while ago, I had a moment of revelation. I was on an archaeological site and somebody asked me how old a particular stone was. I knew exactly what they meant and had asked myself the same question plenty of times before: when was this stone put here or made into this shape? But in that instant I realised how ridiculous the question would seem to a geologist: ‘oh, about 500 million years old!’

And after that, everything seemed to change about how I looked at the world. I still feel that sense of layered time, but there is another voice in my head that whispers, when I think of Rome or Istanbul or Athens or Varanasi that where I am right now, wherever that may be, is really just as old, or maybe even older.

(In case you’re interested, the rock I’m currently sitting on is about 315 million years old. In comparison, Rome is actually a geological baby: the oldest rock beneath the city is a mere 5 million years old and much of the city is built on the remains of volcanic eruptions from only 40,000-70,000 years ago. Istanbul’s geology is complex but seems to come in mainly between the 55 million and 23 million year mark. The acropolis in Athens is perched on rock deposited as river sediment about 100 million years ago and the bedrock of Varanasi dates from a whopping 1.6-0.5 billion years ago, so the world really does look different if you’re a geologist! And of course, look back before all of those processes of rock formation and it is all just stardust…)

Anyway, the upshot of this is that thinking of one place or another as older or younger is pretty ridiculous. But we still do it, all the time. Not every culture sees value in the same things or in the same ways, but the idea that people have been here (wherever here is) for a long time is quite common. It can be enshrined in stories, everyday practices and the remains of things people have done.

Ruins

I was recently in Lucca for the first time and found myself in another city of Italy that lives with its built past in a unique and clearly visible way. Lucca may not be part of your top 5 itinerary for places to visit in Italy: it doesn’t have the biggest (or oldest or best) Roman arena, like Rome (or maybe Verona), or the crookedest belltower (like Pisa) or the most extensive underground dovecotes (like Orvieto). It does, though, have a lovely, relaxed vibe and a great cycling culture, not least because the medieval walls around the city provide a perfect circuit, with stunning views. And in the middle of the city there is another circuit - a much smaller one. Because, once upon a time (specifically, in the 2nd or 1st century BCE), Lucca did have a pretty good Roman arena - not the biggest or the best but still a good one. And it was Lucca’s.

When the Roman economy of the early first millennium contracted, shipping in lions and bears and leopards became a luxury too far. Then the rise of Christianity called into question the ethics of making men fight to the death for entertainment. Some cities, like Constantinople, turned to chariot racing instead, but many didn’t. They were smaller anyway because the shrinking of the Roman economy, as well as wars and instability, reduced the population of cities. Instead, their arenas fell into disrepair or became occasional venues for community gatherings.

And the people of the past, like us, were an unpredictable mix of sentiment and pragmatism. They could put effort and resource into maintaining things that served no practical purpose any longer or that make little sense to us and they could look at a Roman arena, towering over their city, and think, ‘hey, that’s a lot of tonnes of really well-cut, top-quality stone that we don’t need to schlepp in from the quarry and finish ourselves!’ All over the Roman Empire, arenas when the lion-and-Christian shows ended, aqueducts when the water stopped flowing, walls when they turned out no longer to be in the right place or the right size, bath bouses, tombs, temples and roads, were transformed into homes, churches, other walls and other roads.

But there were other choices that could be made. In Lucca, people looked at that arena, towering over their city, and apparently thought, ‘hey, that’s a set of really good walls, already standing, that we don’t need to build or mortar and, wow, just look at the view, the central location, the cute little piazza in the middle now all those lions and leopards have gone!’ People moved in. What had been terraces of seats became apartments. Restaurants and shops opened in the tunnels where gladiators had once marched. On the sand in the middle, people sold their wares.

It is still that way today.

I’ve always been fascinated by how people re-use and live with old buildings and Lucca really brought home to me how one of the things this re-use does is make places distinctive. There is no city centre that looks the same as Lucca or feels or moves the same as Lucca. The medieval walls and then the Roman arena in the centre give Lucca a unique gyroscopic quality, as if everything rotates around and within these two circuits.

The idea that a unique history and one that is visible in the fabric of everyday life makes a place distinctive - makes it itself - can be found in all sorts of places. In ancient Greece, citizens of many islands wrote histories linking their own little patch of rock and earth to bigger myths and legends, explaining how specific outcroppings, coves and buildings were the setting for battles, miraculous events and fabulous transformations.

Rituals

It isn’t just ruins or other distinctive features that make places, though. I’ve said that Lucca moves differently to other cities but this can be concentrated, made into a collective act, through processions and festivals. I was recently in another place where the recurring layers of practice create space, identity and community. It is somewhere that fascinates me every time I go and that has shaped my thinking about how we choose to belong to and create communities across time.

Siena might look, if you just passed through it, like many another northern Italian city. It has a fancy duomo, narrow streets overhung with high brick buildings, some medieval walls and gates and plenty of people happy to tell you how amazing it is and which parts of global history and art were made there or began there. (Siena’s claims to fame in this respect include, but are definitely not limited to, a decent case for being one of the places where international banking as we now know it got going, some wonderful Renaissance stone floors and a superbly preserved cathedral library, stuffed with very early examples of written sheet music.)

Look a little closer, though, and you might notice some stranger things. In one part of the city, over doors, around windows, in the metal grilles of a gate, you’ll see snails. Somewhere else, it’s an elephant on a tower or sneaky little porcupines peaking out of sign boards. Peer down a street and you might see rows and rows of tables, laid out for a party - a really, really big party. In some places you may see a church with a very low step at its door or even a wide ramp.

In the Middle Ages lots of cities all over Europe had guilds, parish associations, block groups - all manner of clubs and affiliations that gave people professional advantage, charity, support and a sense of identity. Siena was no exception. Then the city faced a series of setbacks. The Black Death in 1348 took out more than half the population. A century or so later, Siena began to fall behind in competition with its major rival, Florence. Eventually, in the 16th century, Florence conquered the city, which had fallen in population from perhaps 50,000 in its heyday, to only 10,000.

The associations located in the 17 sections of the city, known as contrade in Siena (which, as far as I can tell, are more or less the same as what are called sestieri in most other Italian cities, but no Italian city is quite like any other), became the most important organising associations in people’s lives. You could still be a member of guilds, parishes, socities and clubs, sure. But everyone in the city was a member of a contrado and, for most people, that was the group that absorbed most of their time, attention and money. Contrade provided support for members in need, communal dining rights if people paid an annual subscription, celebrations for births, marriages and deaths and… entertainment.

The first recorded horse race in the main piazza of Siena dates from the 16th century. These days, they are a phenomenon. They are known as the ‘Palio’, from the pallium, or long, decorated cloth that the winning contrado gets as a prize. That’s right: all you get is a piece of cloth! The races (there are usually two a year) take about 70 seconds to run. But they are much bigger than a 70 seconds for a piece of painted cloth.

Ten horses race each time. Contrade draw lots and compete to be one of the ten teams running. The distribution of horses is also by lot and the race is won by the horse, not its jockey, so horses crossing the line without their rider can still bring home the victory. Conniving and conspiracy are all part of the game, which lasts all year. Contrade form alliances and foster old rivalries. There are blessings, street parties, hiring ceremonies for jockeys, flag parades and Renaissance costume processions. The unique colours and symbols of the contrade (usually an animal) fill the streets.

There are about a hundred posts I could write just about the Palio of Siena, which these days is a major media sensation. People with windows looking out into the piazza can rent their apartments for thousands of Euros a day. What stood out to me on this trip, though, was the making of place and community: the Palio isn’t an event. It is a calendar - an annual cycle of rituals and routines, deeply embedded in space, from the communal kitchens in each contrado to the meals that effectively shut off whole streets or the leading of horses into the contrado church before a race. (The overlap between religion and the contrade is definitely quite a few of those hundreds of posts: the horses are blessed at the altar, as are the jockeys, who are nevertheless ‘outsiders’, each contrado has its own equine-accessible church but this is not the same as the parish church...).

The Palio is a massive commitment of time and energy, spanning generations. For a kid in Siena, being chosen as a flag bearer for your contrado is cool. If you have a friend the same age from Florence or Rome or Naples, they probably don’t get it. Men and women spend days of their lives cooking and putting out tables. Famous Sienese who leave often come back for the races and donate their professional skills and networks to the contrado. A year in the life of Siena only makes sense in the context of the contrade and even if there are people who don’t much care (and I’m sure there are!), it will still shape when and where they can move around their city and when other people in their social circle will be available. Place is made by material but also by action.

Revenants

Lucca and Siena were both wodnerful places to be and travel almost always puts me in a good mood, anyway. There is something not just about seeing new places and meeting new people but about the fact of being on the move that brings me joy. As a result, when I’m reflecting on the ways that people make places, I’m usually seeing the world through slightly rose-tinted spectacles. (I also wear light-reactive glasses so, as well as looking a bit like the Terminator the moment the weather gets good, I literally am seeing the world through tinted specs!) That can make it easy to look on the bright side of the past, too. It can all seem like romantic ruins and exciting events.

History, though, is the repository of the bad as well as the good. It is the past of all that we have been. Memories of grief and trauma are one of the most powerful ways we place ourselves in the past. That is some of the overlapping charisma of ruins and rituals: they aren’t just collections of stones or orders of service. Old buildings can ask us to imagine the lives lived in them. Rituals have power because they are done over and over and, when they span generations, they offer us a chance to picture a moment in other lives - a moment when we know they would have been doing, hearing, seeing, smelling the same things as us, from the scent of a traditional family recipe to the roar of the crowd at a Palio race.

But there are also the moments we remember because we they were extraordinary. We are glad we don’t share them with the people of the past or, if we do, we do so safely. These are the other places of memory: graveyards and memorials, that have their own special relationship to ideas of place.

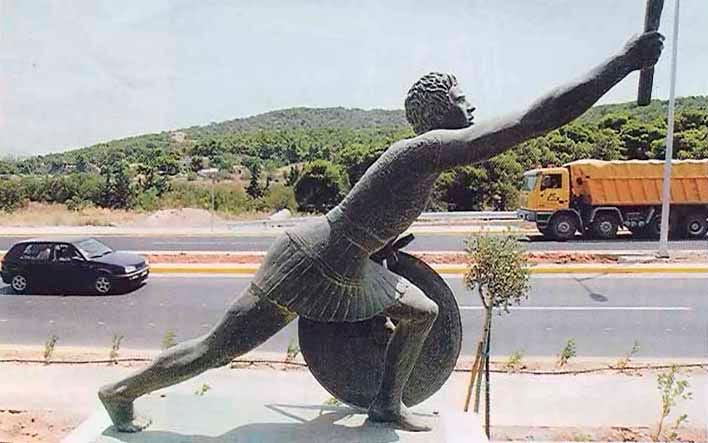

The earliest recorded war memorial was erected on the site of the battle of Marathon and it is a fascinating case study of land, ritual and memory, of writing ourselves across time into the ground on which we tread.

The year was 490 BCE and the city states of the Aegean had been at intermittent war with Persia, to the east, for some time. News came of a large Persian army approaching Athens, one of the two most powerful of the Greek city states. The other was Sparta. Herodotus, who wrote what is often called the first history about these wars, states that a runner, Pheidippides, or Philippides (the name varies in different sources), was immediately sent to Sparta to ask for help. The journey of around 246km (153 miles) took him two days but the Spartans were in the middle of a major resligious festival. They could not send troops for 10 days. Pheidippides brought the message back that the Athenians, along with allies from the much smaller city state of Plataea, would have to try to make their stand at Marathon.

The story of the battle is long, involved and told perfectly well in many places (including by Herodotus), but involved the Athenians and Plataeans playing for time for as long as they could, knowing that every day brought Spartan help closer. In the end, though, the Greeks were victorious. Pheidippides leapt into action again, running the 40km (25 miles) from Marathon to Athens to cry out to the assembly, ‘Chairete! Nikon!’ (Hey! We won!) before dropping dead.

If you visit the plain of Marathon today, two earthen mounds still stand out against the flat land. One contains the ashes of the fallen Athenian soldiers, as Athens preferred cremation at that time. The other contains the bodies of the Plataeans who fell in the battle, since the Plataeans favoured burial of their dead. There was once also a victory column on the site.

The mounds (often called tumuli) have become landmarks down the millennia. The remains in them were treated differently, owing to the rituals of the two communities, but they look almost identical. The memory of them has been preserved by generations who have repeated the story (helped, in this case, by the fact that Herodotus and others wrote it down, but oral cultures, too, use features of the land as focal points for keeping stories alive).

Pheidippides and his feats of athleticism have created a very different memorial of space. His final, fatal run has become the basis for the length of the modern marathon. Every time a limber runner pins on their number and lines up in London, Boston or Chennai or anywhere else in the world, they are marking in space, wherever that space is, the journey of a man 2600 years ago. The scenery may be different but read any runners’ website, with advice about how to cope with the 18-mile downer or keep something back for the final stretch and there is a thread of memory, connecting every body that has run that gruelling distance.

In 2004, the summer before I began my undergraduate studies, I remember watching the Athens Olympics. Team GB was fielding arguably Britain’s greatest ever long-distance runner, Paula Radcliffe, who was widely tipped to, finally, take a coveted Olympic gold. The organisers had leant into the historic moment with a route that led from Marathon back to Athens. The day was scorching, heat haze shimmering on our family TV screen, rising up from the asphalt as Radcliffe climbed one of many hills, pouring with sweat, starting to shake. She bowed out at 23 miles.

It wasn’t her day. It wasn’t her race. And back then I wasn’t a historian (or a runner), but that moment stuck with me. It brought home the story of Pheidippides, which I’d heard before as something glib and throwaway: have you heard the one about the guy in ancient Greece who ran from Marathon and dropped dead..? He became a person, pouring with sweat, starting to shake, marked in time and space.