Do you struggle to sleep?

I do. I’ve tried most tricks over the years - lavender on the pillow, hot cocoa before bed, a calming wind-down routine. Counting sheep. These days, though, whenever I count sheep I always imagine the same sheep: these sheep…

They aren’t very lifelike sheep. The artist hasn’t exactly captured them in moments of dynamic motion. That was never the point. These sheep are purposeful, orderly, gleaming and identical. And if we follow them, their destination is not a good night’s sleep but something much more profound.

These sheep are part of a remarkable mosaic programme from the Church of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe in Ravenna, Italy. It is remarkable for quite a few reasons. First of all, that it survives is really quite miraculous. The mosaics of Ravenna are now recognised by UNESCO and draw visitors from all over the world but in the 1500 years and more since they were first put up, buildings across Ravenna were partially stripped to decorate wealthy homes and palaces in other cities, especially Rome and Venice, in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period. Then the city was bombarded during the Second World War.

Sant’ Apollinare in Classe was, arguably, even more vulnerable because it isn’t located in the heart of the city but outside it, where the port of the city had been in Antiquity. These days it is far from the sea because of coastal changes. Walking into the building today, its scale and the vivid decorations underline a sharp contrast between the area of Classe as it is now - quiet and almost rural - and a building clearly designed to host large congregations and important visitors.

Modernist flocks

The sheep in Sant’ Apollinare in Classe are very different from those produced in mosaics in Ravenna a few generations earlier. Take a look at this image of Christ as the Good Shepherd in the so-called Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, made between c. 425 and 450 CE, so around 100 years before Sant’ Appolinare in Classe.

It is, of course, possible that people had lost the ability to produce such lifelike sheep, and once upon a time that was the standard explanation for why later antique art looked the way it does. But there are various reasons for not accepting that argument. Originally it was an argument based on the assumption that, after the classical period of Roman history (roughly the 1st and 2nd centuries CE), things just got progressively worse in every way imagineable. Now we know that the Mediterranean of the 5th and 6th centuries, when the mosaics of Ravenna were made, was still hugely wealthy and culturally sophisticated, with artisans and mosaicists able to move and share ideas and source exotic minerals and specialially made glass tesserae for creating their images. Plus, the mosaicists who decorated Sant’ Appolinare in Classe had those examples of naturalistic sheep in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia literally just down the road to learn from and copy if they had so wanted to. They didn’t.

Well, maybe they just couldn’t get it right? To answer a question with a question: does it look as if they even tried? We do have examples of mosaics from elsewhere in the Roman world that show mosaicists trying their best with limited skills and resources. We can see the sorts of things that went wrong.

As the grinning she-wolf shows, lack of resources is reflected in a limited colour palette. The tesserae aren’t small enough to create complex, subtle shapes and shading. The proportions of the main figure are out of alignment with one another and difficult features, in this case, a dog’s muzzle are… not completely convincing.

By contrast, in the lambs of Sant’ Apollinare, the mosaicists obviously had access to a wide range of colours and materials, including the vivid green that is so distinctive of this design. The tesserae are small enough to create sharp lines, texture and shading and for them not to be immeidately visible to the naked eye, especially from ground level. And finally, from a technical perspective there is evidence of considerable skill, not just in creating figures that are proportionally coherent but also that fit the shape of the space. Upright figure of Saint Appolinaris, for example, and the cross, appear upright when viewed from the ground even though they are actually created on a concave surface. These were not incompetent or amateurish mosaicists.

It seems clear, then, that we need a different explanation than ‘maybe they just couldn’t do any better’. We need to understand why people wanted their church to look the way it does.

Humans have always experimented with abstract, geometric forms alongside naturalism. One isn’t better than the other, even if we might have personal or cultural preferences. Take a look at this incredible work with colour and shape, also from the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, so right next to those naturalistic lambs.

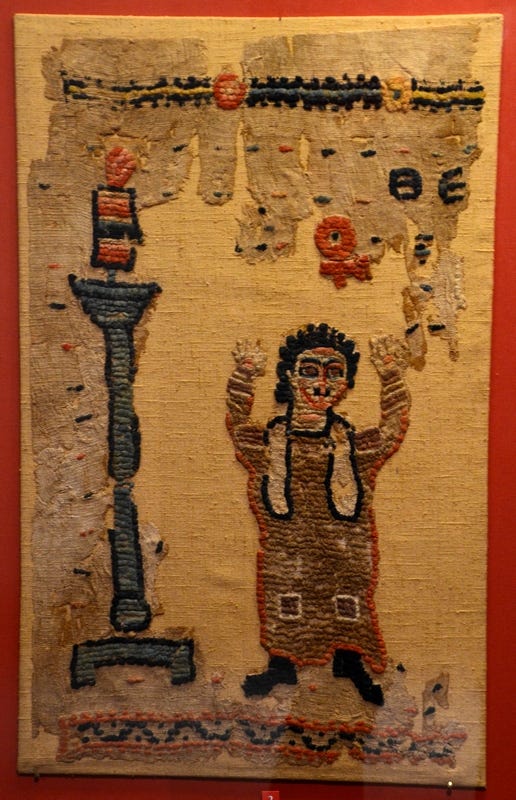

In the period often now known as Late Antiquity, or roughly from the 3rd century CE to the 7th or 8th, when Christianity and Islam were both emerging as world religions, shaping the visual and cultural world of Afro-Eurasia, abstraction in art became extremely popular. It is a shift that seems to have been closely aligned with changing ideas about the world and what lay beyond it.

Christian Art for a Christian Empire

Christianity became, in pretty quick succession, first tolerated, then legal, then effectively, then actually the official religion of the Roman Empire, then ultimately, the overwhelming majority religion of the Mediterranean and its surroundings - a process that lasted from the 4th century to perhaps the mid-6th. By that point, as far as we can see, most arguments were about what sort of Christian you were rather than whether you were Christian or not.

There were some exceptions. Jews continued to practice their faith and became a more clearly defined religious minority within a Christian empire than had been the case centuries earlier, when Judaism had been one among many beliefs under Roman rule. Some people preserved the old ways, the faiths that are now often labelled ‘paganism’. We are told by the 6th-century author Procopius, for example, that it was only in his lifetime that the Platonic academy in Athens was closed down. This had been a major centre of learning dedicated to the works of Plato and other ancient philosophers.

Still, it was more and more true that most people and the public self-presentation of the Roman Empire were Christian. And for a religion that had been, until the 4th century, a persecuted underground sect, this meant a chance to work out a whole new public programme. What should a Christian dress like, act like, where and what should a Christian space look like?

The answers varied from place to place and from topic to topic and they inevitably changed over time. Some decisions the Church (as an organisation) intervened in centrally, as far as it was able: how specific people should be represented came to be quite tightly controlled. The layout of key elements in churches, such as where the altar would be in relation to the congregation, was quite quickly standardised. Others remained more flexible.

In the end, dressing like a Christian didn’t involve changing all that much, except for priests and monks and nuns, whose clothing became more elaborate or distinctive over time. Acting like a Christian could now include wearing jewellery or buying household ornaments with Christian symbols or stories on them. Over time, wearing relics or other objects associated holy sites or figures became commonplace. Specific gestures of prayer developed. In much of the modern Catholic world the practice of crossing onesself, or drawing a cross by moving the right hand between sholders, chest and head is one of many ways of publicly acting Christian.

At such a long distance in time, though, it is the buildings by which Christians publicly proclaimed their faith that survive best. They quickly became a way for individuals, families and congregations to demonstrate their piety and to show off in a world that, like today and everyday, valued competitive consumption. Churches (as well as, eventually, moasteries, shrines, pilgrim hostels, hospitals, schools and orphanages) became part of the landscape of the medieval Christian world.

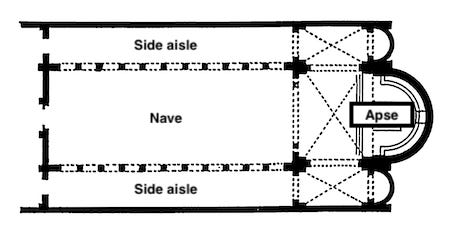

One way of transforming the physical world into a Christian one was to take over pre-existing buildings. It set the pattern for one of the earliest and still most popular forms of church building: the basillica. Initially basilicas were civic buildings, which also shared features with temples. They were open, columned spaces, usually with steps up to the entrance and a porch area, a wide open central aisle and a raised area at the front. (I’ve also talked about basilica churches here.) Even when new Christian churches were built from scratch, many kept this form, while others experimented with a central square shape with wings coming off it or with smaller, simpler open rooms.

Sant’ Appolinare in Classe is a basilica church and the mosaic art works perfectly with the shape of the building, drawing your eye down that huge, high central aisle to the mosaics in the apse. As most churches, including this one, were built with the apse facing towards the east, the morning sun would have flooded in through the large windows. The geens are vivid as springtime and the sheep gleam bright white.

By the time this church was decorated, Ravenna had already been a hotspot for magnificent mosaic decorations for over a century. The mosaicists not just knew this but were working closely with designs from other buildings in the city. After all, my wouldn’t they? Each of the major buildings that survive today has its own distinctive dominant colour, giving each one a unique atmosphere and visual impact but uniting them at the same time into something that feels like a programme. They also trace the developing fashion in Christian art from a focus on naturalism, which came straight out of earlier fashions in Roman art to abstraction and more rigid forms.

Perfect figures

Sant’ Appolinare in Classe feels angular, clean, precise. Its whole programme has a geometric rhythm that is almost hypnotic. Inside the dome, sheep looking upwards, process towards a central point, while above them, the saint of the church and the stylised trees all reach up to the cross. Above the dome, another set of sheep process upwards again, this time pointing towards an image of Christ in human form. The whole design doesn’t just pull the eye upwards. It also hints at an endlessness, an infinity of sheep, which might spring into movement and continue their identical procession up through the intercession of the saint and Christ, forever into heaven.

The number we can actually see, though, even if we imagine innumerable sheep, is not accidental. In the dome procession there are twelve and then there are twelve above the dome (plus another three joining the saint right in the middle of the harmonious and orderly field). Numerology, or seeing significance in specific numbers, was a big part of early Christianity. Some of it is pretty obvious and still has an important or everyday place in Christian cultures today:

3 is the Trinity, God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit;

12 evokes the apostles who followed Jesus… This weekend I’ll be making a simnel cake - a traditional British Easter recipe - which features 12 marzipan balls on top, usually said to signify the 11 apostles (not including Judas!) around the edge of the cake and a 12th marzipan ball in the middle representing Jesus.

But Late Antique Christian numerology could get a lot more complicated.

12 could also evoke the 12 tribes of Israel and the 12 sons of Jacob, underscoring the link between Christianity and Judaism.

7 could stand for the 7 days in which God created the world. It could also stand for the Trinity (3) + the 4 Gospels or their writers, the Evangelists, Matthew, Mark Luke and John. Or it could stand for Heaven (i.e. the Trinity = 3) + Earth (represented by the 4 seasons and the 4 cardinal directions). Because there are so many symbolically excellent combinations of 3 and 4 plus significances of the number 7 in its own right, 7 has always had a special place in Christian art.

6 was considered the number of humankind, because God created humans on the 6th day and people work for 6 days a week before resting on the 7th, but it is also a combination of 3 + 3.

40 represented trial and suffering for faith: the Israelites wandered in the desert for 40 years after the flight from Egypt, Jesus fasted in the desert for 40 days before his crucifixion.

I could go on. These numerologies still matter in different ways and to different degrees to Christians all over the world today, but in Late Antique art there is often a real sense of excitement at working these things out in the first generations of public Christianity, of seeing and showing a world with Christian belief and stories threaded through every simple detail. How much any of this mattered in people’s everyday lives almost certainly varied day-to-day and from person to person, but for the makers of church mosaics, it can seem like stepping into a Technicolor whirlpool that draws you deeper and deeper.

The 2 sets of 12 sheep become the Apostles following Christ and the tribes of Israel walking towards heaven and also hint at the infinity of souls early Christians imagined joining the faith: the division of each set of 12 sheep into two processions of 6 (the number for humankind) is both symmetrical AND underlines the fact that the sheep can represent ordinary people working (the 6 days of labour each week, followed by the Sabbath) to live Christian lives. The 3 sheep in the meadow can represent the Trinity, but the two to one side can also signify the Apostles, who were sent out 2-by-2 to preach to the word, while the one on its own can stand for the unity of God and, together with the saint, they create 4, the number of Earth showing the divine acting in the world.

In the meadow are 8 trees, 4 on each side, representing the Earth (see above) but also birth and resurrection: Christ appeared 8 times to believers after his resurrection, God saved 8 people from the flood in Noah’s ark and in Jewish tradition, newborn babies are circumcised on the 8th day after birth. Even though Christians had, by this point, rejected circumcision as a requirement, they were still happy to use the symbolism and codes that had developed in Jewish belief, which also has a strong tradition of numerology.

Above the apse, the 4 Evangelists, represented by their symbols - a man, an ox, a lion and an eagle - come 2-by-2 to Christ, forming the number 5, which is both the Trinity (3) + the spreading of the good word (2)…

At this point, you might be wondering, can’t this be played with pretty much any number? After all, there can’t be too many (if any!) that aren’t some combination of 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 or 12 (and yes, there are also symbolic associations with 9 and 10, as well as them being combinations of 3s, 5s, etc.). I’m not going to work out if there are any or how many because it doesn’t matter: since the number 1 also represents the unity of the divine Trinity and of all people in God, it is true that every number can be seen as some combination of different sacred symbols and values. And that is the idea!

A mosaic like the apse decoration of Sant’ Appolinare in Classe was meant to get you thinking because each act of thought was a moment spent contemplating the really big ideas encoded in these simple number systems: see a 3, think of the Trinity. See a 12, think of the Apostles. See a 7, think of the Trinity and the Gospels and Creation and the Sabbath… The whole thing is one big mnemonic for Christian stories and ideas and that is perhaps one reason for the move away from naturalism and towards abstract forms.

These mosaicists didn’t want unique sheep, each one doing its own thing, with its own particular look or leg colour or ear arrangement, like that relaxed flock around Christ in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia. They wanted sheep that could, each and all, stand simultaneously for oneness, three-ness, for humans, for Apostles, for Israelites, for the peaceful, calm meadows of heaven, for the abundance of the kingdom to come, for the virtues of meekness and gentleness, for the pure white of light and virtue, for the sheep that would be judged and sent to the right hand of God versus the goats who would be sent to the left...

There is no way to know what exactly or how much any person involved in decorating this church, or who ever worshipped or went into it believed. There is no way to know this about any other person. But we have plenty of texts talking about colour, shape, number and picture synbolism in Christianity in this period and plenty more talking about how to connect the stories of Judaism with Christianity. We have everyday objects and graffiti showing ordinary people incorporating shapes and symbolic number arrangements into their lives in public and private ways. There are magical texts and traditions that have survived to the present, for example around food and festivals, that call on these ideas, in Jewish and Christian practice.

At the very least, even if we assume that it was simply an intellectual game with no faith behind it, it gives us an insight into why people may have chosen specific designs, shapes and arrangements. To my mind, though, it seems like a lot of effort to go to if people didn’t find meaning in the things they saw and created. It also seems like a bigger risk as a historian to assume that whole cultures were consciously lying to each other and to whoever they thought might come after them, than to start from the assumption that people were trying their best to represent ideas and realities that mattered to them, as they understood them: a public world coming to terms with the spread and rise of Christianity as the official religion of one of the most powerful empires in the world.

A couple of hundred years later, another religion would emerge in the Mediterranean region. Islam originated in the 7th-century Arabian peninsula, where people had had contact with Judaism and Christianity for centuries. It went through a similar process to Christianity centuries earlier: working out what a public Islam would look like. As Chrisitanity had borrowed the style of public buildings that already existed, so did Islam, modifying the design of churches, especially the ones with a central open space and a domes roof, to work as mosques. It also developed the abstract forms of some Christian art, removing animal and human figures to create paradise gardens of floral shapes and geometric motifs that served the same purpose - a reminder of spiritual truth on Earth.

The problem with the sheep of Sant’ Appolinare in Classe is that they don’t actually help me get to sleep. They keep me spinning in endless loops of 3s and 6s and 12s, and winding along mental trails to other churches and mosques and mosaics, but I shouldn’t complain. They are doing exactly what they were meant to: making me think.