Hello,

Welcome back to Coffee with Clio. I hope you’re keeping well.

It’s been a fun week or so, historically speaking. There’s been archaeology in the news! I’m not sure that the findings mean exactly what this article says they do, but it is definitely interesting that in the Iron Age (about 2000 years ago, just before the Romans arrived), women in Britain tended to stay in their own communities, while men moved when they got married.

Plus, who doesn’t love some funky coin hoard reports? In St Andrew’s Church in Eisleben, Germany, workers found four bags of gold coins shoved into the hollow legs of a statue (or a STATUE, if you are an editor for The Sun). It looks like they were hidden around 400 years ago from an invading Swedish army.

Meanwhile, at a nuclear power plant in southern England, builders found 321 silver coins of Edward the Confessor (the king whose death sparked 1066 and all that). Early medieval English coin hoards are quite rare and the coins are in mint condition (a numismatic term that has gone rogue: it literally means ‘in the condition that a coin comes from the mint’). So somebody got some brand new coins then buried them. Then, presumably, something bad happened. At best, somebody suffered a really unfortunate memory lapse but more likely, whoever knew were the hoard was died before they could get it back.

On top of that, the coins were actually found in their purse, which is incredibly exciting! What people keep money in is really interesting and often ignored. Imagine trying to explain the broken sherds of a piggy bank to some future archaeologist:

When children are small, we encourage them to drop coins into a ceramic model of a pig with a hole in its back. The hole is big enough to get the coins in but not big enough to get them back out. Then, when the pig is full, the child can break it to get the money out. This helps children to learn habits of frugality and saving.

Absolutely nothing weird about any of that, right?

And that’s before we even get to how this means that drawings or cartoons of a ceramic pig can be used as symbols for wealth, savings or money.

Still, despite how utterly fascinating this question of how people store money is, for a long time, hoards were seen as valuable for the coins, not the pot or box or bag. Also, these things often rot away. So this new hoard is super cool!

As well as history in the news, I’ve also been having a good time digging around in the fine details of a complex problem.

When did this happen?

It is a pretty crucial question for a historian: when did something happen?

Without knowing that, it’s pretty hard to answer a lot of there questions:

did event X cause event Y to happen? Who knows? What if X happened after Y?

Did fashion A shape fashion B? Maybe, but whether we think that that happened (or how) is probably different if A was in fashion at the same time as B, or if A was in fashion 500 years before.

Is Person 1 talking about the same events in their diary as Person 2 is writing about in their newspaper article, so that we can get two views on the same thing? Well, the odds of that being true are a lot better if we know that Persons 1 and 2 lived at about the same time.

The thing I’m grappling with is: what was the state of relations between the Arabian/Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE? This involves a lot of ‘when did this happen’ questions. For example:

This site was a major port in the Gulf that was involved in Indian Ocean trade, based on finds of coins, ceramics. But when was it a major port involved in Indian Ocean trade? When were those coins and ceramics made and deposited there?

These objects from the Gulf have been found in China or India or Southeast Asia, which suggests trade. But when were they made and when did they move?

These writers talk about Gulf trade with the Indian Ocean but when were they writing and when are they writing about?

I’ve got a couple of posts brewing about these specific questions, which are tangly and tough and so much fun!! But today I want to focus on some fundamentals that, despite being fundamental, are often quite surprising.

It took me a while, for example, when I started teaching, to realise that lots of students starting a history degree think that when is straightforward: you just need to look it up in the right textbook, museum catalogue, encyclopaedia, etc.

So I started asking students, ‘if I tell you that something dates from a specific time, how do you think I know?’

The answers to this have been many and varied but one keeps coming round: there must be some test you can do, right?

There isn’t, but it made me realise that this is something that might not be obvious if your idea of fun is not trawling back through 180 years of articles in obscure journals trying to work out why somebody in 2006 says that such-and-such an event happened in 627 CE, when somebody else in 2003 said that it happened in 625. (This is a made-up example, but I could give you a lot of real ones that are more complicated to explain in a sentence but amount to the same thing.)

In some ways, that confusion is a case of the profession doing its job too well. By the time most people see the results of historical working out on TV, in books (especially school text books) or in museum displays, there is an answer: this document dates from 1475, this building was built in the mid-sixth century, this coin was struck between 1894 and 1901. Great!

But what if we dial back? How do we know any of those things?

Relatively and absolutely

The first thing to think about is what kind of ‘when’ we are looking for (and is possible with the evidence we have). There are, basically, two kinds of ‘when’:

‘When’ relative to something else: it is possible to know that A happened before B, which happened at the same time as C, which happened before D without necessarily being able to put a date on any of these things. If a document says that Huviska ruled after Kanishka, for example, and that Huvishka was succeeded by Vasudeva, then anything we can be sure happened/was made in the reign of Kanishka must be older than something that happened/was made in the reign of Huvishka or Vasudeva. (This is a real example from the Kushan Empire of northwest India, which was powerful between roughly the 2nd century BCE and the 3rd century CE. For a long time, though, nobody knew exactly when specific things happened within that broad timeframe, even if they had a documented date, because the Kushans used a dating system that recorded when things happened counting from the start of the reign of Kanishka and we didn’t know when that was.) This kind of ‘when’ is referred to as ‘relative dating’.

Alternatively, we can think about ‘when’ in the absolute sense: this means being able to fix something in time, but it doesn’t mean that we always have the same level of detail. Saying that something happened at ten past nine on Tuesday 21st January 2025 and saying that something happened between 1980 and 1988 are both absolute, not relative dates, but one is clearly more precise than the other.

Obviously, the most detailed absolute date for everything is what we’re always aiming for but, depending on when and where you’re interested in, it might be necessary to work more with relative versus absolute dating or precise versus broad absolute dating than in other times and places.1

It also depends on what you’re interested in. Specific events happen at precise times, but if you’re interested in processes, the answer might always be less precise. I can tell you that I started my current job as a historian on 1st September 2021 but when did I first become interested in history? Definitely some time before 2021 and after 1985!

In my work, I spend a lot of time asking how people know when…

It says so…

The single commonest, clearest and best indication of when a historical artefact or document dates from is usually on the object or document itself. After all, lots of stuff today has a date on it and so it often was in the past. Legal documents, diary entries, letters, and objects stamped with customs duty seals or hallmarks will often, helpfully, just tell you when they were made.

There can be complexities. The dating system might not be one we use now (see above, for the date of the Kanishka Era). But as long as somebody has worked out how two different dating systems compare, then there will be a chart to consult and you’re sorted.

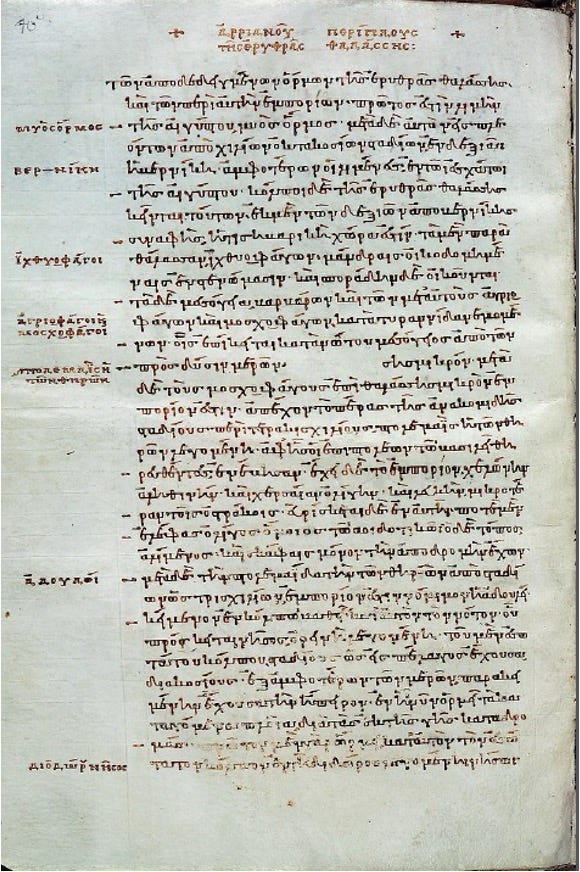

One Byzantine/Late Roman historian, who was writing a chronicle (a year-by-year account of history) in the late 8th and early 9th century, went for a real belt-and-braces approach.

Most years in the Chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor are dated according to:

Anno Mundi, or Year of the World: this was the number of years since the world had been created (according to Biblical time).

The Year of the Divine Incarnation: this is what we also call Anno Domini (= in the year of the Lord), which means the number of years since the birth of Jesus. A little bit of adjustment is still needed for the fact that Theophanes was not using the Gregorian calendar but this is the date that is easiest to recognise.

The year of the reign of the emperor who was ruling at the time of the event. So, for example, for an event that happened in AD 525, Theophanes would also give the date 6025 Anno Mundi and the 6th year of the emperor Justinian.

In addition, for a lot of entries, Theophanes added:

the year of office of several major church leaders, e.g. the 1st year when John was bishop of Rome.

the names of the two consuls (the highest Roman civic office) of that year. Since these had, traditionally, changed every year and been the most important people in the empire during their year of office, this had, once upon a time, been a really good way of absolutely dating things in Roman history, but by the time Theophanes was writing, people could hold the office for a long time and, in any case, it wasn’t a very important role any more. This was definitely showing off!

the year of the reign of the Persian emperor: this is seriously weird. Theophanes doesn’t do it throughout the chronicle, with each of the Roman Empire’s rivals, but for the period between the 3rd and the 7th century, when the Roman Empire’s main rival was the Sasanian Persian Empire, he sometimes also includes the regnal dates of this arch-rival.

For added excitement, the Roman year did not begin in January but September, so unless we know the month when something happened, we might not be able to map a single year from Theophanes to a single year in whatever modern calendar we’re using. If, for example, Theophnes just says ‘[something] happened in AD 525’, then we would have to say that it happened in 524/25 of the modern Gregorian calendar, as it could have happened any time between September 524 and August 525.

If this is starting to make your brain hurt, it does mine, too. Luckily, there are people who deeply love this stuff and dedicate their whole careers to doing the nitty-gritty working out that means, if you pick up a modern copy of Theophanes, there’s a nice little note at the top of each entry of what the relevant date is in the modern Gregorian calendar.

The joy of cross-referencing

Probably the next best way to date something, if it doesn’t just tell you, is by cross-reference. Even if something doesn’t tell you when it was made, it might mention something else that we do know the date of.

From my own work, coins often tell us the name of the ruler who issued them. They don’t often tell us the date when that ruler was in charge, but if we know that from another source, like a written chronicle or a monument, etc., then we can also pin down when the coin was created.

Then, if a coin is found in, say, the legs of a statue, we can at least guess, using the date of the coins, when they were deposited and, in some cases, maybe when the statue was made, for example, if the coins were placed in the statue when it was made, rather than being added at a later date.

Layers of time

Coins in statue are a good lead-in to another method of dating: finding how things form layers or, in simpler terms, what is underneath what? In archaeology, this is called ‘stratigraphy’ and it is difficult to do and to interpret, especially when a site is complicated.

(Sites can be complicated for all sorts of reasons. Rabbits, for example, can make a site very complicated very quickly, dumping stuff from lower down higher up as they excavate their warrens, or digging holes that let stuff from higher up fall down…)

The principle, though, is simple. If one thing is underneath something else, and you can be fairly sure that it hasn’t been messed around with (e.g. by an archaeologically indifferent rabbit), then the thing underneath must be either older than the thing on top or, at least, the same age as it. The thing underneath cannot be newer than the thing on top of it.

Imagine, for example, excavating a building. You find a floor - a very nice floor, covered in fancy tiles and laid on a really uniform, strong, flat foundation. If somebody had dug through that floor after it was laid, you’d be able to see the marks. There aren’t any. It is in perfect condition. That floor dates to 1066. (Let’s say you got very lucky and some nice person put an inscription on the floor saying, ‘In 1066, for the good of his soul, Bishop Albertus paid for this floor to be laid’). You dig down below that floor and you find another floor with objects lying on it. You can be pretty sure that everything below that tiled floor was there before 1066, then it was sealed in by the new floor.

As you can see, this method on its own only gives us relative dates: layer 1 is newer than layer 2. But if we can find absolute dates for any of the layers (for example, because of that very handy inscription), then we can start to pin things down in real time.

And you can go further.

If you find similar looking stuff (let’s call it Type X Stuff) at, say, a hundred sites, and it is always in the layer beneath some other stuff (let’s call it Type Z Stuff) that looks the same from one site to another, too, then you can start to establish periods: Type X Period and Type Z Period.

Based on the stratigraphy, Type X Period must have come immediately before Type Z Period. Then, when you find a new site, you can look at the stuff and, hopefully, it will look like stuff you have already seen, so that you can say, this is a Type X Period site.

When you hear somebody on TV saying ‘archaeologists have discovered a new [Viking/Maya/Neanderthal/Iron Age/Roman] site’, what they usually mean is: we have dug up a whole bunch of Type Viking/Maya/etc. Stuff from this site.

I’m glossing over a million and one difficulties here, but this is roughly the principle behind archaeology.

Changing fashions

Historians do something similar with style. It is a lot more limited and often not as reliable, but the idea is the same: fashions change and if you can figure out roughly what style came before or after another, you can start to put things in order.

This works best with things that have to be done over and over again in every generation. The study of handwriting is a great example. It has its own name: palaeography, or the study of old writing.

People have to be taught to write, and most people will teach the next generation to write the same way that they themselves write. But, things still change. They can change slowly, because each generation doesn’t write exactly the way they were taught, or they can change more quickly.

In ninth-century Constantinople, there was quite a rapid change in handwriting because more people started writing more than they had in the previous few centuries, but the supply of parchment for writing on was about the same. As a result. people looked for a way of writing more quickly (so they could write more), and smaller (so they could use less parchment).

Even when documents have no direct date on them and no information to cross-reference, palaeographers can often date a manuscript to a few decades.

The same works for other kinds of stuff: tablewares, clothing, hairstyles (usually in statues or paintings), jewellery. This is called stylistic dating, because it is establishing a date based on changes in the style of things.

Imagine turning on the TV. There is a show on, set in your home country. How long does it take you to figure out when the action is meant to be taking place? Do you need somebody to tell you? Or can you get quite a long way by looking at what people are wearing, the music in the background, what the cars look like (if there are cars!), the way people are speaking, even the way people are behaving or moving?

What you’re doing is relative stylistic dating in action.

Scientific tests

I said at the start that there aren’t scientific tests to tell us when things happened/were made. And that is true in the sense that there isn’t ‘some test’ we can do on [whatever we’re interested in] that will tell us ‘this happened/was made on 14th July 1652 (Gregorian calendar)’.

But there are scientific tests than can help.

Just for some examples, carbon 14 (often just C-14 dating) can be used to determine when something organic (plants or animals) died. Dendrochronology can be used to pinpoint when a piece of wood was still part of a living tree. Thermoluminescence dating can reveal how long certain kinds of stone have been out of sunlight.

The challenges of scientific dating are:

Each one can only be used on specific kinds of material. Metals? No chance! Unless a metal object has a date on it, refers to something that can be dated, is excavated from a stratigraphic context, or can be stylistically dated, there is zero chance of pinpointing when it was made.

Lots of scientific techniques are destructive, so you need to cut or drill a sample from an object or grind the whole thing to powder. The fancier or more famous the object, the less chance anybody is going to let you do that.

Scientific tests can also require expensive equipment or access to labs, which means if you can’t afford the kit or you can’t move the object to where the lab is (for example, because it is a national treasure, is stuck into a wall or weighs several tonnes) then you’re out of luck!

Not everything is suitable for scientific dating even if it’s made of the right material. Dendrochronology relies on ‘rings’ in tree trunks. Thicker rings form in good years and thinner rings in hard years. Across wide regions of the world, we now have master patterns: if your wood sample has a year-by-year pattern of ‘good-good-hard-less hard-really hard-okay-good-really good-good’, then you can look at the master pattern and see that this specific (made up) sequence corresponds to, say, 1540-1549. But… you need a big enough piece of wood to identify a sequence of rings, and the wood needs to have been cut across the grain or you can’t see the rings at all, so just having a piece of wood doesn’t mean you can date it this way.

What the dating technique is telling you might not be what you want to know! If you want to know when a building made of wood was put up, you might do some dendrochronology. Let’s say that gives you a date of 1570 for the outermost ring visible on the wood. What is that telling you? The test says that the part of the timber that you have chosen came from a tree that was growing in 1570. That might give you a rough idea of when the building was made, but only if you have some reason to believe that the building was made with freshly cut timber, not wood reused from another building or left to age for several years to dry out AND that the piece you have chosen came from pretty close to the outside of the tree when it was cut down. To turn a tree into building timber, people usually strip off the bark, but they might take off a lot more than that, and you might be looking at a plank from close to the centre of a tree that had actually kept growing for decades before it was cut down. Oh, AND you have to take into account the possibility that the wood you’ve chosen might be a repair to the original building.

So scientific tests have their uses, but they are not a silver bullet. (In fact, if we had a silver bullet, it would be almost impossible to date, except to ‘after the invention of guns’).

When things lie

All of the techniques above are why, by the time history gets out into the world, we can usually say with some confidence ‘this happened/was made then’.

But the complications are enormous.

What about things that have been re-used or recycled? What about when old-fashioned things come back into vogue?

Some documents straight up lie: there’s no point forging a will if you put a date on it that is after the person died!

Lots of documents make mistakes. I keep a daily journal, except that sometimes I don’t for a few days. When that happens, I go back to complete it (because I’m that sort of person): I don’t know about you, but sometimes, trying to remember what I was doing on Tuesday when I sit down to fill in my journal on Thursday can be a struggle. Did I talk to mom and dad yesterday or the day before? I write it down in Tuesday’s entry then remember an hour later that I actually spoke to them on Wednesday. Do I go back and correct my journal, or do I figure that I’m only writing for me and anyway, what matters is that I called my parents, right?

Now imagine being Theophanes the Confessor, trying to write your chronicle entries on the last couple of hundred years of events. He tried his best - we know he looked for as many other people’s history writing as he could, that he searched for documents and, for the more recent past, asked people who were involved, but those ‘did I call my parents on Tuesday or Wednesday?’ errors still add up. Some were his and some probably came from the people whose work he used.

Spartacus and the Roman wristwatch

As common as these sorts of mistakes, and much more common than outright lies, are anachronisms, or ‘things without time’, meaning things that have been put into a time when they don’t fit.

In the 1989 US Civil War movie, ‘Glory’, a child raises his hand to wave some soldiers off to war, and on his wrist? A digital watch. Hopefully, nobody has ever watched that scene and thought, ‘Oh, wow! I never realised they had digital watches in the Civil War’.

Anachronisms are usually more subtle though. Take police. Detective/crime fiction is hugely popular. Historical crime fiction has its own pretty big niche, and lots of historical dramas have a crime/mystery elements. And sometimes, when I’m reading/watching these sorts of stories, somebody will say something that is obviously an effort to ‘translate’ the phrase ‘we should go to the police’.

But if your book/show/film is set in the Middle Ages, who are you going to call? (Hint: you’re more like to find somebody whose job description is Ghostbuster than Police Officer.) Let’s try:

‘We should go to the sheriff!’ The sheriff’s job involved a lot of things, including to make sure that people didn’t cheat at the market, round up trouble makers, report to the local lord about bandits, insurrection, or major outbreaks of sickness… It was not his job to go out and investigate things because somebody thought that somebody else might have broken a law (unless, maybe, it was one of the laws about cheating at the market or forging coins).

‘We should go to the abbot!’ Okay, if your problem was about the spiritual or physical health of one of his monks or one of the monastery’s mills had burned down. It was not the abbot’s problem if, for example, young women around the New Forest were mysteriously going missing (unless they were running away with his monks).

‘We should go to the king!’ Actually, not the worst idea, but still - and tell him what? He’s in the middle of planning to invade Wales (this story is set in England) or go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem or marry the King of Sweden’s second cousin and you and your crime-detecting sidekick would like him to know that somewhere in the New Forest, somebody is up to no good, maybe. Good luck!

‘We should got to the magistrate!’ Probably the best option going? At least one case from 9th-century al-Andalus (the parts of modern Spain and Portugal that were under Muslim rule for parts of the Middle Ages) does involve a magistrate pro-actively investigating a murder by analysing evidence and calling witnesses, but he may have been a bit unusual. Mostly, the magistrate would expect to find out about your issue when you had a case to bring.

There is no good answer because the idea of one person whose job is to do all of the things that a modern police officer does (and not do a bunch of other things that we don’t ask police officers to do) is pretty recent. Lots of parts of modern policing were done by somebody, but not necessarily the same somebody.2

The anachronism here is not that people are imagining modern police wandering around in the Middle Ages. The anachronism is that people are imagining that certain parts of the world of the Middle Ages must have been basically like now, but wearing different costumes.

This might be because somebody wants something to have been the same: there must have been somebody doing the job of police officer, or my best-selling historical detective novel won’t work!

It might also be because it can simple and almost subconscious to fill in the blanks from what we know. This tendency gets worse the more abstract, huge and everywhere the things we’re filling in the blanks with are.

In the nineteenth century, it was everywhere and taken as a general truth that people identified as the citizens of nations and that that was one of the most important ways of organising things like politics, warfare and trade. As a result, even scholars who knew an eye-wateringly incredible amount about their period of study still imagined people centuries earlier as citizens of nations.

They wrote about kings ‘leading their nation’ or suggested that this group of people would have had a reason to fight this group of people because of their ‘national identity’. We now know that the process of people imagining their world this way was long and slow and didn’t happen in the same way or at the same time everywhere. (Trying to understand 1066 and all that in these terms, for example, gets pretty confusing.)

People in the past did this invisible ‘filling in the blanks', too. And so, we come back to where I began, trying to figure out the ‘when’ of Gulf-Indian Ocean trade in the 3rd-6th centuries.

We have lots of documents, written by people in the 9th-12th centuries. They are writing about centuries earlier, and they say things like ‘and so the ruler in [let’s say, the 4th century] seized control of the great port of [place]’.

The place in question was definitely a great port in the 9th-12th century. But was it in the 3rd-6th centuries? When he says ‘the great port of [place]’, does our author really mean ‘the place that was a great port in the 4th century’? Or does he just mean ‘the place (which is now a great port)’?

For the author, and for some modern scholars, the idea of bustling, long-distance trade is so abstract and huge and everywhere (every historian writing today is a child of globalisation) that it just makes sense when talking about a large settlement near the sea to think of it as a port and to assume that, if it was involved in trade at some point, then it must have been involved in trade at all points.

But what do the coins and the pots and the buildings say? When was it a port?

That is my work for the next few weeks and, eventually, a post for here, but in the meantime, when you’re next doing relative stylistic dating yourself, ask yourself: what exactly do I think looks ‘a bit old-fashioned’ about that person’s outfit or dining room suite or taste in music, and how old-fashioned do I think it is? And how do you know?

This is not quite as simple as ‘things get more precise as we get closer to the present’. That is a factor: we just document more in the modern world than people did in the past and the documents are more likely to survive, at least for now. But what you’re looking at still makes a bigger difference. Not everything is documented even today. For some things, like criminal activity, documentation might be a hindrance. For other things, it may simply be that nobody has thought to document something. During the Covid 19 pandemic, for example, there were some fascinating (and grim) case studies about how different countries record deaths: what details do you take, how do you get people to report them (centrally or locally?), does it include everybody? There are bits of ancient or medieval history for which we can reconstruct what specific people were doing, hour by hour, day by day, with forensic precision, and whole areas right now where there is no reliable record of when a person was born.

Actually, as real police officers point out today, this is often true of modern detective fiction, too, where the lines between police work, pathology, crime scene forensics and the prosecution team can get a bit blurred, but that’s somebody else’s blog to write!

Thanks for the insightful post. Now I'm going to bed, hoping my dreams will be safe from... *shivers* archaeologically indifferent rabbits