Hello and welcome back to Coffee with Clio.

The quality of coffee I’m taking with my history is higher than usual this week. I’m in Venice, giving a series of lectures about medieval history for the John Hall Venice Course.

It’s amazing spending time with keen and interested students and wonderful subject experts. It’s also fantastic to be back in one of my favourite cities in the world.

January is also possibly the best time to be in Venice. The winter light is incredible and the streets are quiet.

Given what I’m up to this week, I figured that I’d write something about Venice (which I have done before and absolutely will again!) or perhaps about the Byzantine Empire (which I have done, here), since I’m lecturing here about how it connects with Venice. But the wonderful thing about travel is Serendipity.

Geneva, City of Refuge

I travelled to Venice via Geneva, as it was a chance to catch up with a friend who is about to move to the other side of the world. One morning we took a stroll. Suddenly, my friend pointed at one of the city’s hidden treasures.

Ooh, a medieval tower! The Molard Tower was once part of the defensive walls around the major harbour of Geneva. It was built in 1591. These days, it is still a centre for public events.

That wasn’t exactly what my friend was pointing at, though. It was this, on the wall of the tower:

My friend was pointing to a relief panel in the wall of the tower, put up in 1920. It celebrates Geneva, ‘city of refuge’, a reputation that it has claimed at least since the Reformation, when Protestant thinkers were escaping from Catholic authorities elsewhere in Europe.

Carved from a pale stone, very different from the other rocks of the tower, it depicts the personification of the city of Geneva, reaching out to welcome a refugee, who is propped up on one elbow.

Do you recognise him, my friend asked.

I confess, I looked for a long time, feeling a little foolish because this was clearly meant to be obvious. I had the feeling you get at a party when you bump into a person you know you’ve met before, but, without some other hint, the connection will not resolve, the memory will not obey. You stand there desperately hoping that they will give you a clue or somebody will come along and greet them by name.

Then I did what being a historian trains you to do: think context!

Could it be William Tell? He’s an icon of Swiss national identity! But we don’t really have his likeness. Usually you can tell it’s Tell from an arrow and an apple somewhere in the picture.

What about Zwingli? I’ve been to Geneva enough times to know the city is very proud of its 16th-century Protestant reformers!

Hell, I thought, maybe if I take a few steps to the left and get the sun out of my eyes, I’ll recognise the first-century Roman emperor Augustus. He had a thin face and has a tendency to turn up all over the place, though he wasn’t exactly a refugee! But there was a Roman presence in what is now Geneva. The city even has at least one other piece of wall art celebrating the Roman connection, so maybe that was it?

It would be a bit of a stretch to call some of those figures refugees, though.

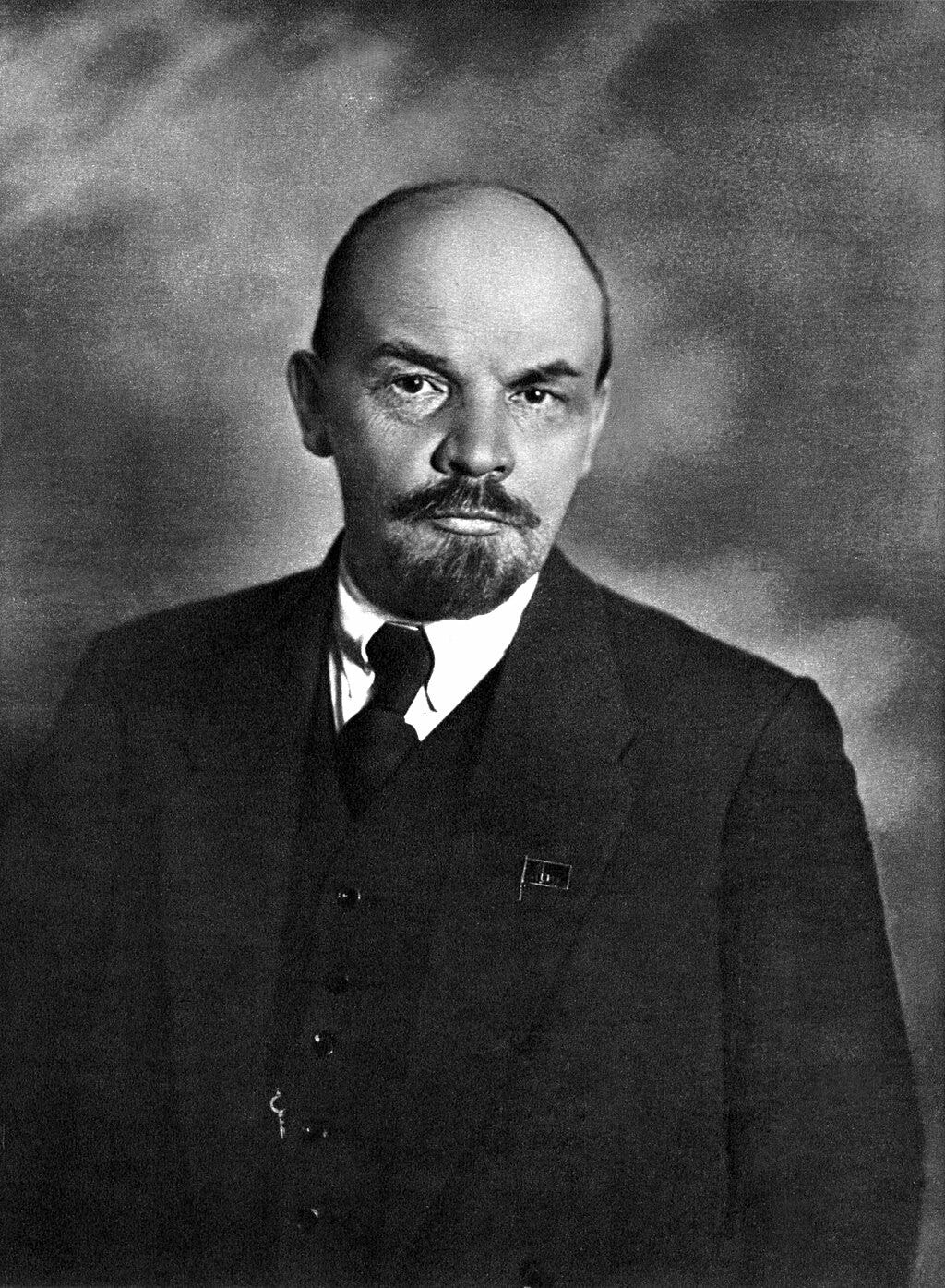

As soon as my friend said ‘it’s Lenin!’ the pieces all fell to earth: a face I knew from a thousand textbooks, posters, statues and photographs.

I’m not quite a child of the Cold War. I don’t really remember the fall of the Berlin Wall, but I did study Russian for seven years and did quite a bit of Soviet history at school. I’ve visited Russia a few times, and various countries that were part of the Soviet Union.

Lenin’s is a very familiar face.

I just didn’t expect to see it here, in the wall of a late medieval tower in downtown Geneva.

At the start of the twentieth century, though, you might have expected to see Lenin’s face in downtown Geneva. He was a refugee in the city in 1895, 1900, 1903-1905, 1908 and intermittently between 1912 and 1914. And he wasn’t alone. Swiss universities were popular among female medical students from Russia. Together with political activists fleeing the Tsarist authorities, there was a community of more than 2000 Russians in Geneva.1

Having said all of that, there is no definitive proof that the relief is of Lenin. There is no inscription or artist’s notebook. It just really, really looks like Lenin. In fact, it was easy enough to find out that there is no proof that the sculptor intended to depict Lenin because other people have gone looking for that proof before me.

This, in turn, raises a question: if it looks like Lenin, and Lenin was a refugee in Geneva, why would we need more evidence that it is Lenin?

Lenin has always been an ambivalent, complex figure. Individuals usually are.

That severe jaw and shaven head are so deeply recognisable but he has not struck everybody who has looked at the relief as a particularly suitable icon for the refugee. From his refuge, he contributed to a revolution that changed the world. And, like all dictators, he was ultimately responsible for causing quite a few other people to need refuge.

By contrast, groups or categories of people, such as ‘refugee’ are often imagined in very simple terms. Categories easily become stereotypes, and stereotypes of refugees can often focus on ideas of innocence, powerlessness and passivity.

Of course, historically, that doesn’t make any sense. Just as anybody can become a refugee, so too, anybody can be a refugee. There’s no requirement to be nice or innocent or powerless. Still, for some people, Lenin hasn’t seemed to fit the stereotype well enough, leading to scepticism about who the figure in the relief really is.

Perhaps more reasonably, some people have suggested that if you were looking for a representative of any group for a public statue, you might try to find the nicest person in that group that you could, or at least a good balance of nice and famous. So, yes, Lenin was a refugee, but if your point is about how important it is to help refugees, rather than, say, about Marxist politics, is Lenin the poster child you would choose?

This argument makes more sense to me, and honestly, Lenin probably isn’t the person I would choose as the figurehead of… well, very much really, except maybe Leninism. But it isn’t my sculpture.

Since there is no official proof that the sculpture is Lenin, I can’t speculate as to why he might have been chosen, but plenty of other cities have plaques or memorials recording that he stayed there. Maybe it was just that, this time, famous won over nice.

I’m pretty convinced that that face really is Lenin, with or without written proof!

Project #Not Quite

As I boarded an early morning bus two days later to head to Venice, I was still thinking about the face on the wall. I wonder, I thought, if there are any statues or carvings of Lenin in Venice?

Venice is somewhere I go quite often so I’m always interested in finding new treasures to hunt, to get me off the beaten path and into new parts of the city. Italy had a strong connection with the global communist movement in the twentieth century, so it seemed very possible that there might be some Campo di Lenin somewhere or a bust on a bridge.

This quest took me down a couple of rabbit holes. I now know more than I ever expected to about Soviet art exhibitions, for example, but, as far as I can tell, there is no Venetian Lenin to find.

Instead, I found something even stranger…

…a ghost in the machine, a history of a future that never came to be, a statement of intent that has become its own memorial to a time gone by.

2017 was the hundredth anniversary of the 1917 communist revolution in Russia, which brought Lenin to power over what had been the Russian Empire and would come to be known as the Soviet Union (or, in full, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or USSR).

2017 was also a Biennale year in Venice.

The Venice Biennale has been held more or less every two years since 1895. It is a grand art exhibition, which includes gallery displays but also bigger installations and art trails all over the city. In art circles, it is a very big deal and attracts some very big ideas.

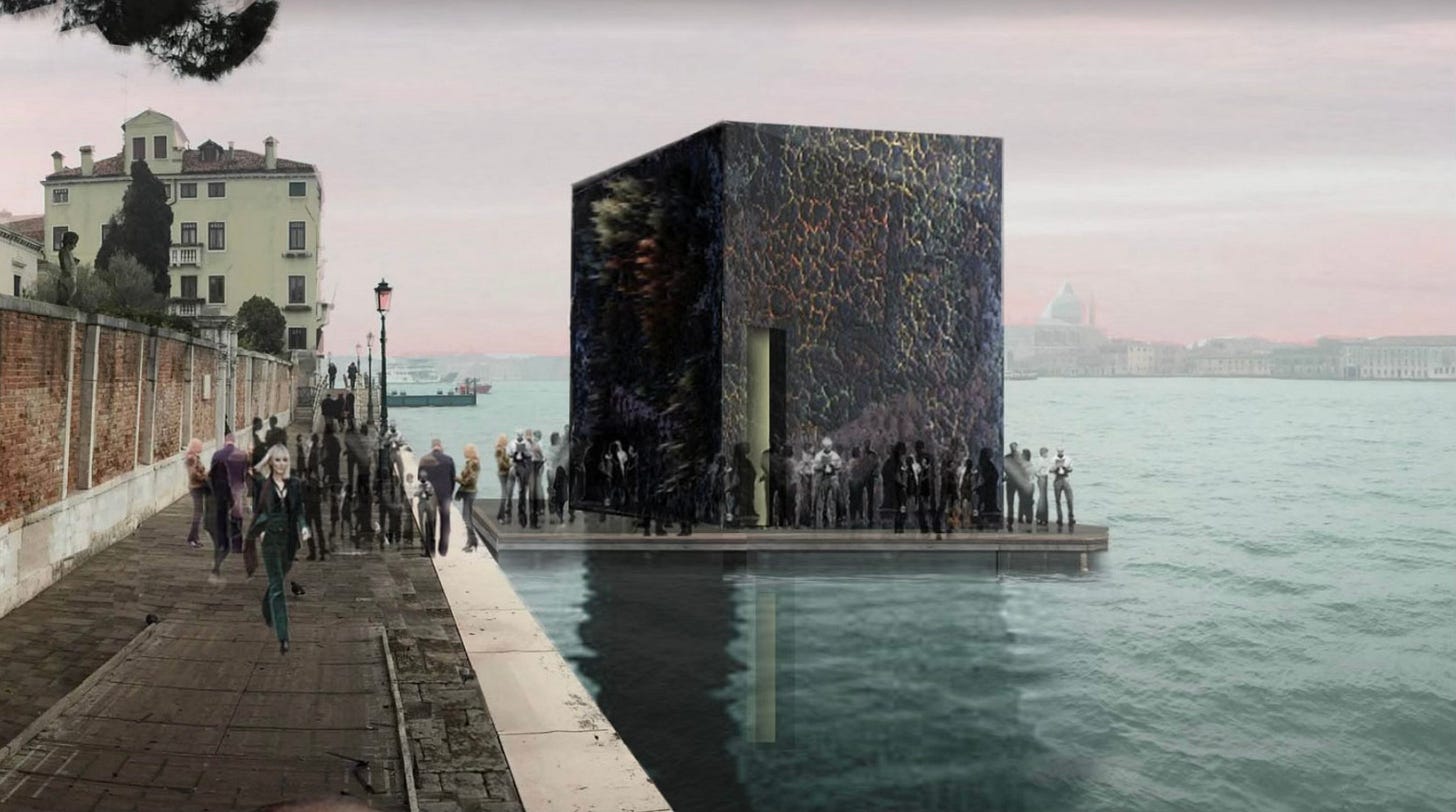

Object #1 was a very big idea.

From May 2017 Object #1 would float along next to the Fondamenta della Zattere, a pretty modern, trendy part of central Venice, insofar as the old city has ‘modern’ bits.

Visitors would step onto a floating pontoon, at the same level as the land, and could walk around a large black cube. This cube is a reference to a painting made in 1915 by Kazimir Malevich, called ‘Black Square’. It is considered to be one of the most significant works of the Suprematist movement. This movement was closely related to expressing the ideas of a new world order in art: in short, if the political and social world was to be remade by a socialist revolution, what would the art of the new world be?

‘Black Square’ became literally iconic in early Soviet culture. It was suggested that Soviet citizens should all have a black cube in the corner of their house where Russians had traditionally put icons of Christ, the Virgin or Christian saints, as a secular shrine and a place for contemplating new, revolutionary truths.

Inside the cube at Zattere, which visitors to Venice could enter through a tall, narrow door, they would find a 60-seat amphitheatre, with room to sit and contemplate. Centre stage would be a recreation of the sarcophagus of Lenin, by the iconic early Soviet modernist architect, Konstantin Melnikov.

Inside the sarcophagus, but visible from only one angle, would be a detailed digital reconstruction of the embalmed body of Lenin, which is still on display in Moscow today. From all but one angle, though, the body would not be visible but would instead appear to be a black void. This is the origin of the name of the project. When Lenin died, ‘Project #1’ was the code name given to his body as the Soviet authorities figured out what to do with this first secular saint of the communist revolution. Now, apparently, less than 23% of Lenin’s body remains after a century of conservation, so what is the ‘content’ of the body in the tomb?

A body that becomes a black void, like the black square, was designed to provoke viewers, a hundred years after the Russian Revolution, to wonder about the futures it imagined, the role of an individual, the transience of matter and the persistence of ideas…

Except that, in the end, it didn’t.

At some point between March 2017 when several articles (for example, here) were written about Project #1 and May 2017, when it was supposed to go on display, the project ‘encountered difficulties’ and was withdrawn from the Biennale, but with plans to be shown in the future. That future did not come to be either.

Now the project is described on the website of the architectural firm, Skane Catling de la Peña, which, along with GRAD (Gallery for Russian Arts and Design) and Factum Arte, a company specialising in digitising art and heritage, was meant to put the display on.2 It is described as a project that was once imagined but is not currently expected to materialise.

So, hello, Lenin.

A face on a wall that might not be Lenin and a digital image that was always meant to be Lenin but, in the end, wasn’t.

A black cube that Malevich wanted to transform how people thought about the past and the future and a sarcophagus to show off a body that is now more lost than not.

A journey with ghosts: a revolution that shook the world and echoes in art and with my younger self who never expected to be exactly here, but then, probably neither did Lenin!

There is quite a helpful blogpost here which goes into far more detail about Lenin’s time in Geneva, which is especially useful if you fancy a Leninist tour of the city.

In the world of small worlds, I’ve worked with the work of Factum Arte before, as they were involved with a project to digitise the Hereford mappa mundi, one of the most remarkable medieval maps in the world. On top of this, it turns out that one of the company’s founders is also an alumnus of the John Hall Venice Course.