Hello and happy Friday,

I’m writing to you on the road again, this time on my way back from Venice, which is a city that always has something new to offer. This was a wonderful visit and, as always, there was the mandatory ‘hello’ to the Palazzo of San Marco. The facade of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice is covered in treasures from Byzantium, most of them brought back to Venice after the sack of Constantinople in 1204 (which I’ve written about before).

The display was meant to be beautiful but it was also meant to be boastful: Venice had brought low the Roman Empire itself and plundered one of the richest cities in the Mediterranean. But one piece on the cathedral has always struck me as particularly gruesome.

It is a head made of porphyry, a dark reddish-purple rock that the Romans thought was a marble but geologists now agree is not. It was prized for its rich colour and for being very hard and therefore difficult (and therefore expensive and showy-offy) to have things made of. It could also only be mined from Mons Porphyritis, or the Porphyry Mountain, in Egypt. Thus, at least until the 7th century, using it was a reminder that the Roman Empire controlled the massive resources of Egypt. After that, porphyry in the Mediterranean was mostly re-used from earlier monuments, so it became a different kind of showing off: it demonstrated that one had the wealth (or force of arms) to appropriate Roman stuff and the taste and education to recognise the best bits.

The head is not the only thing made of porphyry on the front of San Marco. There are also the tetrarchs, a group statue of four men shaking hands with one another, representing a short-lived effort at formalised collaborative government in the late 3rd- and early 4th-century Roman Empire. The statue was probably made in the 4th century, though it could have been made a bit later. There are also some columns. They all probably came from Constantinople in or shortly after 1204.

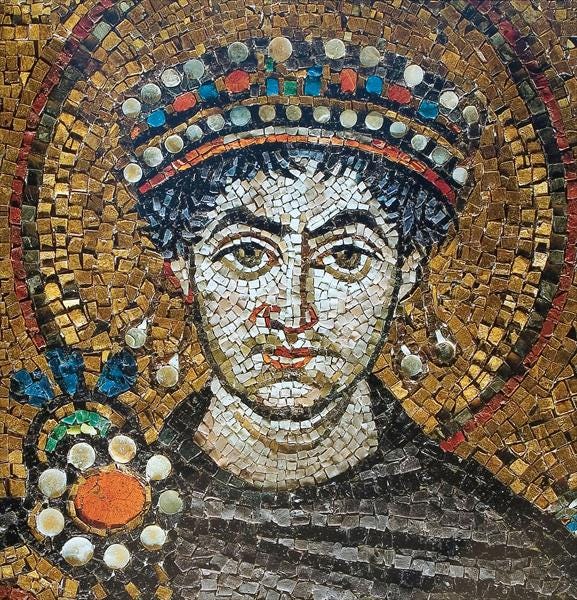

Conventionally, the head is described as a head of Justinian I, who ruled the Roman Empire from 527 to 565 CE. He was an energetic sort of emperor, overseeing legal reforms, tax reforms, religious persecutions (mainly Christian on Christian), and several major wars - with Persia on the Roman’s eastern frontier and with various ‘barbarian’ regimes that had taken over some of the western regions of the empire. His generals managed a short and very effective war in North Africa, a longer and less conclusive one along the coast of modern Spain and a very protracted, largely pointless one in Italy, that took 20 years to sort of win and seems to have caused quite a lot of people in Italy who had cheerfully thought of themselves as ‘Romans’ up to the point to decide they actually preferred the barbarians, thanks.

Justinian’s life was colourful in other ways, too. He seems to have been happily married to a woman for whom he persuaded his uncle (the emperor before him) to change Roman law: up to that point emperors could not marry women of such low social status. They had no children and he never remarried after her death.

Justinian stands out for all of these reasons but also because we have quite a bit written about him by one of the most prolific and interesting of the historians of Late Antiquity (roughly the 3rd to 8th centuries CE). Fortunately, Procopius wrote a lot and had personal access to court and the events he recorded. Unfortunately, he never could seem to decide what he actually thought of Justinian and has left us two opposing accounts: Greatest Emperor EVER (along with his lovely lady wife) or Literal Hell Demon (and his scheming, sexually voracious harridan bride). It isn’t just hard, but actually pretty unsafe to say much about who Justinian really was but that doesn’t much matter to the porphyry head on the parapet of San Marco.

A matter of identification

Is it really Justinian? Honestly, I’d say that is probably a bit of a historical shoulder shrug. It might be Justinian: he was a famous emperor, who loomed large over imperial politics in his day and for generations afterwards and it is totally possible that he or somebody else might have ordered a porphyry statue of him. The figure is definitely an emperor and the style of the imperial crown lets us place it pretty confidently in that 4th- to 6th-centuries, so right on target for Justinian’s 6th-century reign. On top of that, the face is clean-shaven, which Justinian always is in other portraits we have of him. He wasn’t the only emperor who preferred a fuzz-free face in his official presentation, though.

People have also argued that the face looks a bit similar to Justinian in those other portraits we have: a bit chubby cheeked and dour. But the most famous of those portraits comes from a mosaic in Ravenna, where Justinian never went, and might have been made by somebody who had never seen him. And the other portraits come from coins, where the fashion had stopped being for showing people how they actually looked, rather than as idealised ‘imperial’ figures, some time before.

Besides, porphyry itself is part of the problem. As we’ve said, it is very hard, making it very difficult to work. It also isn’t that well-suited to finely carved detail as it isn’t super fine grained. As a result, porphyry carvings, whether they are people or plants or abstract geometry, tend to focus on simple, clean lines. Personally, I like them but that’s a matter of taste not history. Whatever your aesthetic preferences, porphyry carvings are not the best place to look for accurate likenesses.

So the head might be Justinian. It might not be. Being such a famous emperor it is completely possible that somebody had a porphyry statue made of him or that his was the name people reached for when they began writing about the engimatic head on the balcony.

Off with his head!

Justinian’s isn’t the only name the head goes by though. The other is connected purely with Venice. It had nothing to do with Byzantium or Constantinople but everything to do with how the Most Serene Republic (as Venice called itself, La Serenissima in Italian), chose to display this particular bit of loot. I said I always find it a bit gruesome. Why? Because it is unmistakably, unsubtly intended to look like a decapitated head on display.

Maybe the original statue was already broken long before 1204. Maybe it got broken as somebody tried to collect some moveable loot to bring back to Venice. There is a headless porphyry statue of a late Roman emperor in Ravenna, which might be the rest of it.

We’ll never know for sure but, at some point, somebody in the middle of Venice had a head and they looked at the parapet over the cathedral of the city and thought, ‘You know how this would look great..?’

So there it sits, like some fresh trophy deposited on the wall, a colour that the Romans themselves thought of as like blood, staring out into the lagoon, announcing to new arrivals in the Republic of St Mark that this is what happens to the incautious. (For what it is worth, that kind of signalling isn’t unusual historically: displaying the bodies of enemies or criminals at the borders of a state or in its political centre is a long-standing method of political communication.)1

But which unfortunate gave their name as an alternative and why? The head has often been known as La Carmagnola, referring to a man by the name of Francesco Bussone, born some time around 1382 to a peasant family near Turin, in northwest Italy. The 1300-1400s were good times and bad times for that part of Italy. It was the age of the condottieri, or soldiers of fortune - a mix of foreign and Italian-born chancers, some noble sons looking for adventure, some, like Francesco, poor men chasing opportunity. All of them were keen to exploit the constant warfare between city states in northern Italy.

Condottieri would pull together war bands and rent themselves out to cities that had money, often from the international textile trade, but not enough territory to raise armies from their own population. The condottieri themselves were famous for being unscrupulous, often brigands as much as soldiers, and frequently willing to change employers for better wages or rewards, including noble titles. Francesco himself came to be known as the Count of Carmagnola and rose from a child soldier to leader of his own war band.

For a long time he fought for Milan, including against Venice, but in 1427 he rented his sword to the other side. And that might have been fine: nobody thought they were buying undying loyalty from a condittiero. But it seems that Venice did think it was buying an honest effort to win the war. For the condottieri, though, war was their business. Even more than at, it was their lifestyle. And their rules of war reflected that. They were not hugely invested in killing each other. In fact, many married into each other’s families, switched into each other’s war bands and competed with one another to be fashionably dressed and to hire the best architects and artists to show off their wealth. They helped to create a nouveau riche that was critical to the Renaissance: all of these dangerous men with money to burn, and perhaps in some cases, an acute concern for their immortal souls, were exactly the sort of patrons that ambitious, mobile artists needed. Some sponsored poets and painters to praise the Lord. Others paid sculptors and jewellers for more worldly ends.

Such a man was Francesco Bussone but it seems that, with Vencie, he miscalculated. Why was he not winning more battles? Why did he seem to win one then lose one, instead of pressing forward an advantage and destroying the enemy? Why were prisoners routinely ransomed back to carry on fighting? Apparently Venice offered Francesco money and titles. They kept raising their reward to get him to end the war quickly. Presumably it wasn’t that simple, because these things never are. But even if the bigger, quicker win that Venice wanted had been possible, perhaps Francesco also didn’t push for it because, deep down, he was part of a world that didn’t need or want to imagine the war ever being over.

By 1432, the Council of Ten that ruled Venice had had enough. They invited him to the city to discuss the war and whatever he said wasn’t good enough because Francesco never made it back out of Venice. He was beheaded and his head, we must assume, was displayed as a warning to others who might try to cheat La Serenissima. And from that time the porphyry head has been nicknamed La Carmagnola.

Soldiers of fortune

The irony is that Justinian and Francesco probably would have understood each other quite well (if they’d had an interpreter to help out). Justinian was the nephew of an emperor, but was an adult when his uncle took the throne and before that, uncle and nephew had apparently been quite simple soldiers. They saw an opportunity and rose to the highest level of wealth and power their world could offer and, if Procopius is any indication, were both admired and disliked for bringing tastes and behaviours with them that were not ‘proper’ among the Roman aristocracy. Francesco Bussone lived in a very different world but saw the same possibility to climb the ladders of government and violence, and earned the same admiration and distaste. And perhaps the real head of the Duke of Carmagnola once sat for a while beside the stone head that might be Justinian, looking out into the lagoon with the same dark warning that Fortune is a fickle mistress.

It is certainly clear from the nickname that the people of Venice got the message loud and clear!

It has also been suggested that the head is looking directly towards Constantinople. I’m not convinced. For my money, placing things in space is much more often about how that space works at human scale. There are some specific exceptions, such as the commitment to pray facing Mecca for all Muslims. The challenge of that is reflected in the large array of tools, guides and methods of identifying the direction of Mecca that developed within the Muslim world in the Middle Ages, as well as the slightly irregular alignment of some of the earliest known mosques. In this case, though, I doubt very much whether anybody in medieval Venice cared much which exact direction Constantinople was in but having that head staring down new arrivals as they stepped off the boat in front of the Doge’s Palace? That I’ll buy.