Hello, hello!

Welcome to another week of the past in the present, with or without coffee. (This week has definitely been Coffee Needed for me. A sick cat - now much improved - and a day-trip to London - delightful but draining.) And, in the background of it all, news that deserves its own big announcement in due course.1 It is news of one of those changes that will become a landmark on the timeline of my life. Before. After. Here. There. And that is connected with a question I’ve been wrangling with this week…

You see, I’m trying to finish revisions to my book on the Western Indian Ocean in the first millennium CE (which I’ve also talked about here). It is amazing seeing a project that was a demon under my bed for a decade now reduced to manageable size - just another thing on the ‘to do’ list and an excuse to read some cool stuff. A thing the revisions require, though, is talking and thinking a little more about ‘when’.

So, let me start with a question. If you do drink coffee, do you think of your life before you started drinking coffee versus after you started drinking coffee? No? Shocking! But it begs another question: what markers do you use to keep track of your life?

If somebody says to you, ‘Do you remember when..?’ is the honest answer, ‘No, not really… like, I remember what happened: that was an awesome/terrible/mildly interesting experience, but I don’t remember when it happened at all!’? There are definitely parts of my life that feel like that - I can remember the way things tasted, looked and sounded, and how I felt, but the memory could fit any time in long spans of years.

Mostly, though, I can do better than that. There are landmarks - the school I was at, the job I was doing or where I was living. Those have changed a lot over the years, so if I give myself a moment to think, I can usually pin a memory down by remembering where I was, what I was doing, who else was there. I know for other people it can be children: their life stages make good landmarks. Had they been born yet? Were they walking? Talking? Sulking in their rooms? Wearing baggy jeans that hung down below their underpants? Were they obsessed with a particular video game or movie?

Some people have an uncanny knack for actually remembering dates, which seems to me about as magical as people who just know which way North is. Other people track the story of their lives through music…

What, then, makes a landmark in time? How do personal and shared markers overlap? When they do create collective ideas of time? And how do we put down our own landmarks on other people’s lives?

Periodisation

In history, putting labels on particular spans of time is called periodisation and it is notoriously tricky. You will definitely have heard of lots of periods, whether you’re a keen history buff or just like historical sprinkles on the sundae of your intellectual life: the Bronze Age (or the Iron Age, the Stone Age, the Ice Age and any other Age you might have come across), the Middle Ages, antiquity, modernity…

To choose some British examples, there’s the Victorian era, the Elizabethan era, the Tudor period, the Georgian period. If you’re reading in the US, you might have come across the Federalist era, the Gilded Age or the Roaring Twenties. If you’re from India you may have learned in school about the Harappan or Indus Valley period, the Early Historic or the Mughal and Delhi Sultanate periods and the colonial and post-independence eras. In Europe there is the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. At a global scale, industrialisation and globalisation are processes but they also function as labels for time. I could go on and on, in more detail or across a bigger map.

Some periods put technologies in the spotlight: Stone, Bronze and Iron Age all refer to things people used as tools, which they hadn’t before. The Renaissance and the Enlightenment are shorthands for ways that people thought about the world. Many period labels are to do with who was in charge. There are dynasties (Tudors, Georgians, Mughals), individuals (Queen Victoria), or regimes (the Delhi Sultanate, colonial rulers from outside). Many refer to qualities that later people associate with a period: it was gilded, it was roaring, it was cold!

Period labels overlap, too. Which one you pick often depends on what you’re looking at. Say you’re stuyding British-Indian relations in the 19th century. You might refer to the Victorian period if you’re interested in UK politics of empire. It might be the period of industrialisation if you care about the impact of factory-produced goods on trade between the UK and India. Or you might talk about the colonial or Raj period if you’re uncovering Indian political organisation in response to empire.

If you’re studying big chunks of history there might be all kinds of smaller periods nestling inside your area of interest like matryoshki. And periods can be contentious. One person’s Golden Age might be another person’s Really Pretty Bloody Awful Age and that might just be coincidence but it might not: what if the Golden Age for one group was the major contributing factor to the Pretty Bloody Awful Age for another? Imagine that one group labels a time ‘Golden’ because they won a series of wars that the other group lost…

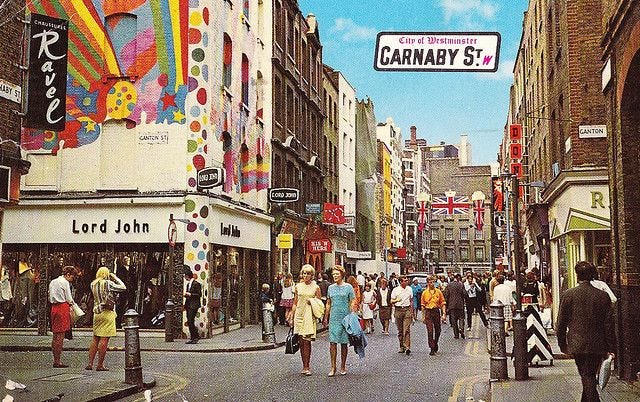

The Swinging Sixties

Let’s take a look at a fairly recent period: the Swinging Sixties. I grew up hearing about the Swinging Sixties - the music, the hippy movement, free love, free drugs, synthetic dyes (suddenly skirts could be both mini and really red!!)...

I guess as a kid, I thought of it as mainly a US-UK thing. Then I went to Germany and found out that it was a thing there, too. The terms and some of the details were different but people were definitely recalling many of the same changes. Lots of other places, though, were definitely NOT swinging in the ‘60s. It was the Cold War so anywhere behind the Iron Curtain was doing its own thing and other places were doing theirs for other reasons. So ‘where’ clearly matters but it took longer to realise how textured and varied the ‘where’ part really is.

Talking to my parents helped with that. They lived in the swinging sixties. Didn’t they? Turns out, yes and no. Sort of. Depends.

There were mini skirts. I’ve seen pictures and my mom looks fabulous in them! There was music. I grew up to a soundtrack of Hits of the ‘60s compilations and BBC Radio 2, which I remember as more or less a ‘60s hits radio station with intermittent news, quizzes and traffic updates.

But apparently both of my parents got through the Swinging Sixties without so much as a whiff of drugs or hippies, except maybe for that trip my dad went on with his dad to London. (And in case you are wondering, yes I believe my parents! I don’t think their reminiscences are an elaborate smokescreen to conceal wildly misspent youth. It is just that, as my mom put it, Wombourne wasn’t really swinging.)

If the where was complicated, so is the ‘when’. January 1st 1960 to December 31st 1969… If only things were so simple!

Both of my parents sort of tuned into the sixties around the middle of the decade, and that seems to have been the case for lots of other people, even in places that might have looked much closer to the centre of things. Part of the problem is that any period is really a sum of many parts, an amalgam of all the things that gave it uniqueness but that didn’t all happen at once. 1967 was a very good year for music (including Leonard Cohen’s first album, for a start!), yet the ‘60s were, mathematically speaking, nearly over by then. But what did ‘being over’ mean? There was no screeching halt on New Year’s Eve 1969, when, like a scene from an Austin Powers movie, everybody switched abruptly to flares and psychadelic music.

One year blends into another, some people throw themselves headfirst into the Zeitgeist. They reflect it and they make it, by embodying a culture and a moment. Others pick and choose or simply overlook some of what is going on, but all of this should make us ask again: when does any period begin or end, and what makes its particular characteristics… particular?

Another way?

One response to the messy, imperfect and sometimes perverse game of periodisation is for people to say ‘can’t we just do without?’ And there are definitely some period labels that we might be better off getting rid of. The ‘Dark Ages’ is slowly dying out and won’t be missed much by anybody who has studied the Middle Ages (though the ‘Middle’ Ages has its issues! The middle of what, exactly?).

I would like to nominate ‘prehistory’ for the junk heap. Back when almost everything we knew about the past came from written records about political affairs, I guess it made sense to divide the past into ‘when people wrote down those kinds of things (= history)’ and ‘before people wrote down those kinds of things (= prehistory)’. Often it was just used as a term for ‘before people started writing’. These days, though, we know so much more about places and times when people didn’t write much, or anything. And we know that, even when some famous individuals were writing long treatises about politics and battles, the vast majority of people were not included in these accounts: they couldn’t write, couldn’t read and probably had very different priorities and interests.

Arguing that specific labels have outlived their usefulness, though, isn’t the same as getting rid of labels completely. After all, we’ve got to have some way of talking about time if we’re going to write about the past. At the very least, we need to be able to say that X happened before or after Y. Depending on what X and Y are, it might quickly become useful to talk about a whole bunch of things as happening ‘before Y’ or ‘after X’ and eventually, isn’t that just another period label, like ‘pre-war’ or ‘post-war’ in 20th- and early 21st-century Europe? (That is starting to break down as a period marker as younger generations don’t immediately know which war it refers to. The past, as a social memory, is always changing.)

Ah, but what about just using dates, you may say! I certainly did. It can definitely be a solution to some problems. In my book about the Western Indian Ocean in the first millennium CE, the same place and point in time might be labelled 5 or 6 different ways, depending on whether the person writing about it was from a certain region, worked as a historian, an archaeologist or a literary scholar, wrote in one generation or another, and so on. Some of the differences are just perverse. My personal favourite is that, on the northeast coast of the Mediterranean, c. 530 can often be labelled ‘Early Byzantine’. On the southeast coast, it will just as often be labelled ‘Late Byzantine’. Just saying ‘the 6th century’ or ‘in the 530s’ can streamline and untangle these issues.

Ultimately, though, we’re back to the Swinging Sixties: whatever it is I say the 6th century or the 530s were like did not begin or end at some neat, tidy point on a calendar and it wasn’t the same for everybody, everywhere. Unless we are literally just talking about lists of dates, saying when something happened or was is still messay. We’re still looking for a… vibe, some quality or collection of characteristics that splodge messily over the lines but look more concentrated in ‘the 6th century’ or ‘the 530s’ than outside them. The 1960s didn’t end with a bang in 1969 but nevertheless, there still was a difference between mini skirts and rock n’ roll and flares and space rock.

Full fourscore

As I wrestled with all of this, it was the ideas I’ve been chewing on here that all came together: parents and children, the changing of generations, handy units, like centuries and decades, and a quote from the Bible (Psalm 90:10) that has found its way into all kinds of popular culture. It gives the usual lifespan of a person as ‘threescore and 10’, years, which is 70, or perhaps, if the person is strong, a full fourscore (80). Average life expectancy, at least in some places, is slightly higher than that now, but not enough to radically change the mass-scale calculations that come out of it, especially if we focus on that ‘full fourscore’.

Looking at time from this point of view, I realised that centuries are not just arbitrary units of 100 years, which is one of the arguments often used against replacing labelled periods with them. If we treat them as splodgy, just as we do with decades like the Swinging Sixties, they are also just a little over that fourscore lifespan. As a result, a century is also about how long it takes for three successive generations to be born, for each to grow up and decide that everything their parents did is out-dated and misguided, to have a go at doing things their own way, then to decide that making the world the way you thought you wanted it to be is much harder than it looks and to become the generation dismissed by the next one along as misguided and out of date.

While many people are fortunate to know their great- and, more rarely, great-, great-grandparents, the stereotype of family relations across many cultures is of a family consisting of the parental, grand-parental and youngest generation. The concept of ‘living memory’ refers to this overlaying of human lifespans: I grew up with the stories of my parents and of my grandparents. Their worlds, going back perhaps 100 years, are real to me through their words and memories and my connection with them. Further back, perhaps 130 years, I might be able to rely on secondhand stories from my parents or grandparents but we are rapidly approaching the line beyond which there is no direct thread. We’re in the realm of record-keeping: the only way to learn or keep track of those more distant times is through making and using strategies of memory, whether those are archives or oral hsitories.

This does not mean that, between a child and their grandparent, the world stays the same: far from it. Technological developments mean that, today, we often think that the world is moving more quickly than it ever has. In some ways that is true, but somebody plucked out of their day-to-day life in, say, 530 and deposited in the same place in c. 830 would hardly have looked around, shrugged and thought, ‘meh, close enough’! But that link, that ‘living memory’ of somewhere around a century, would probably have cut down the suprise factor. The world of one’s grandparents might have been deeply different but it would also be full of fragments of ‘that’s what grandma/great uncle/elderly member of my community’ used to talk about. A century or more later and those anchor points are gone.

At least, this is my hypothesis, and over the course of writing my book, I am more confident of it. Writing history century by century runs the risk of telling a story of the recent past in which the Swinging Sixties gave way abruptly to the utterly different Spacey Seventies and Yuppy Eighties. It imposes cuts on time across processes that were fluid, diverse and almost imperceptible, but the ‘almost’ matters. I think that we do notice time passing, in our own lives and those around us, in ways that are both highly personal and connected to those ‘vibes’ that are about the choices of all of the people around us. And that is where centuries can be helpful if we treat them as what they were always meant to be, like the ready reckoner in the Psalm of threescore and ten. They are a shorthand for time that feels domestic and familiar versus history, that is knowable, but at arms length.

In the end, though, labelling the past is never absolute and is usually a conversation. You are free to disagree with me about what the ‘60s, the ‘70s or the ‘80s were really all about. Historians disagree, endlessly, about what the deal was with the 530s or the 6th century. We fight over labels and put forward our own solutions. Going century by century isn’t a way around this. It is just the choice I think works best for what I’m triyng to do in my book.

The uncertainty of periodisation can be frustrating. I was once asked quite crossly by somebody wanting to test my bona fides as a historian when the Renaissance began. I said that it depended on which Renaissance they meant and what aspects of culture or society we were talking about, or where exactly in the world. They rejected this with open contempt. ‘There are international conferences to decide these things!’ I just didn’t want to admit that I didn’t know. We both left, I think, feeling quite confused by the other.

But when we stop arguing over what we call parts of the past, or even how we chunk it up into those parts, we have really given up on the possibilities of history itself. Because arguments about what a certain time was ‘really’ or ‘essentially’ like, what the dominant colour and flavour of its splodgy essence was, are really ways of triangulating who, where and what we think was important, about where we point our lens and what we think makes changes in the world. And how we look back on all of that should change all the time. We learn more about how things are interconnected. We realise that phenomena that seemed unimportant are actually critical. We find that people who talked loudly about their own power and significance might not have made that much difference after all. And so what we call the past shapes how we imagine our present.

I do not mean the Papal conclave but I could. As I put the finishing touches on this post, white smoke has emerged from the Cistine chapel and Cardinal Robert Prevost has been announced as Pope Leo XIV and, by many a medieval chronicler’s reckoning, a new era has begun.

I remember vividly a rich discussion in one of your Birkbeck Medieval World undergraduate classes on ‘when did the medieval period end’. There was, of course, no agreement and dates suggested by students ranged in centuries. These days, as an Early Modernist, I am getting better at being politely vague before moving the conversation on - usually to the subject of cheese.