Hello and happy Friday,

This is going out to you the day after I get back from a week away. In fact, the writing of this post was periodically interrupted by trying to spot mooses (meese?) from out of a train window. I’ve been in Uppsala, in Sweden, a city with a huge amount of medieval to offer, if you’re interested. Which, obviously, I am!

This was my second visit and the two trips ended up being completely different, yet both all about the Middle Ages. Here I’ll be sharing some of my pictures and memories of a visit in 2022 to the archaeological site of Gamla (Old) Uppsala. I walked the site that time with my partner who is a) a great person to do that with because he approaches a historical landscape, even on holiday, as a project to be unpicked, and b) he is much better at remembering to take photos than I am!

Then I’ll say a little bit about why I was in Uppsala this time round but it has given me a whole list of things I want to tell you about, so think of that as more of a taster of things to come.

Gamla Uppsala

We had not intended to visit Uppsala… So might begin a Gothic detective novel. ‘We’ were me, my partner and my parents in the summer of 2022 and we had not intended to visit Uppsala because we were only stopping off for a couple of days in Sweden en route to our final destination - Tallinn in Estonia, where two of us had tickets to see Rammstein and two of us did not. (No prizes for guessing who did and didn’t.)

It was a great trip and memorable for various reasons. There were still Covid restrictions coming and going all over the world but we made it across France and Germany with only a few nerve-wracking train delays. We loved seeing the gradual changes of landscape and culture as we moved north. And by the time we got to Stockholm we were ready to stay in the same place for a couple of days.

That didn’t mean, in the end, that we wanted to spend all of our time in Stockholm though. Partly, it was ridiculously hot that summer and the city just felt like an oven. And partly, Stockholm just wasn’t really… us. We didn’t hate it and I enjoyed it more coming through on this trip so maybe it was mainly the crazy heat! Whatever the reason, though, after a wander around the National Museum and most of a day in the Vasa Museum (which a friend of ours said was the one museum we had to see in Sweden and he was not wrong!), we fancied something a bit different.

‘Wait,’ said my partner, with the eager look of a medievalist just emerging from Covid brain-fog, ‘if we’re in Sweden, we can’t be that far from Uppsala!’ Distance is, of course, relative, so what I understood him to mean was, ‘I wonder how easy it is to get to Uppsala by public transport from Stockholm?’ The answer turned out to be ‘very’, and off we went. But why Uppsala?

My parents could give you one list of reasons. They spent the day exploring and reported back on beautiful parks, a lovely library, varied architecture and a generally relaxed atmosphere. And I can now confirm that (New) Uppsala is, indeed, one of the most achingly pretty places I’ve ever been, at least on a sunny day in May. (While I was there, everybody kept telling me how lucky I was with the weather, with just a shake of the head when winter was mentioned.)

My partner’s list of reasons, though, and mine, for being keen on a commuter train to Uppsala, might be summarised under the headings ‘Vikings!’ and, more indirectly, ‘Prof. Rosamond McKitterick’. As undergraduates, ten years apart, we’d both taken courses with Rosamond on those charismatic, elusive characters of the medieval - the Vikings - and, as a result, had both read quite a lot about Uppsala.

Now, exactly what ‘Viking’ means is one of those debates that gets knottier the closer you get to it, but for present purposes, let’s say it broadly means people from Scandinavia, roughly during the 8th to 11th centuries CE, who left home, temporarily at first, then more often as permanent settlers, to visit the lands to their south: Britain, Ireland, France, the Low Countries, occasionally Portugal. Some of them also headed eastwards, founding the city of Kyiv and working as bodyguards to the Roman/Byzantine emperors in Constantinople.

The Vikings were feared and fearsome

The main thing they seem to have travelled for was moveable wealth: silver, gold, jewels. A popular target for raiding became rich monasteries (though rich manors and churches and basically anything with the word ‘rich’ in front of it would do). Monasteries were especially tempting because they were often in remote, frequently coastal locations, including islands like Lindisfarne. The people in them were not exactly trained or inclined towards self-defence and they were full of fancy stuff. Viking raiders would pillage, burn, slaughter and leave, taking riches and people with them. Once they realised that those funny southerners would pay a handsome ransom for books, they also took to nicking those, instead of just taking the decorative covers.

After a while, Viking groups organised themselves into large extorting armies: why rob and pillage if you could get your prospective victims to do the collecting part for you then pay you bags of cash just to go away?

The Vikings were creative and entrepreneurial

They spread art styles, technical knowledge and, indeed, people, across northern Europe. They did business on a huge scale for the time, established new market settlements and, by virtue of their extortion, drove economic reform and coin production in the kingdoms they visited. Eventually, some of them became involved in the politics of the southlands, becoming allies in local political struggles, mercenaries and conquering kings. For those of you in Britain, one of the contenders for the English throne in 1066 was a Viking who had made his name in Constantinople and one of the major reasons there was an English throne rather than lots of different kingdoms was because of alliances formed against Vikings, then, shortly before 1066, the empire building of the Viking and King of England, Cnut, who is these days mainly famous for trying to order the tide not to come in, a thing that he probably didn’t do and which, even if he did, would have been a silly moment in a really rather remarkable life.

In Scandinavia, where many Vikings returned after each looting season, and where the ones who settled down still usually had family ties, they also experimented with things they saw in the south, blending local and foreign practices so that this period transformed writing, religion and government in the far north.

And if you read many books about the Vikings, what you will find is a weird double-take between these two realities. One book will tell you the Vikings are sorely misunderstood - they were just a bunch of great blokes trying to cut some savvy deals, make their fortune then go home and marry their sweetheart. Aw, shucks! Another book will spend pages describing the ‘blood eagle’, a gory method of torture and murder involving a live person and their own ribcage that nobody is sure ever actually happened outside the vivid imagination of terrified monks, but that doesn’t mean those monks didn’t have less elaborate deaths to be terrified of. Brutal, man!

Raiders or traders? Lovers or fighters? Artists or arsonists? Of course, the challenging complexity of people is that we can always be both. And if you are looking for a good book about the Vikings, the one I was recommended just this week by somebody whose judgement I trust (and that I now plan to get myself) is:

Price, Neil, Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings, (Basic Books, 2022)

In this complicated, gripping history, full of men called ‘Bluetooth’ and ‘Bloodaxe’, Uppsala was one of the the places to be.

Places of power

Today, Uppsala has a great museum. There are replica hemlets you can try on, some wonderful finds of pots and brooches and really well thought through video reconstructions, models and descriptions of life in Viking Uppsala, but what you’re mainly there for is the site.

You see, one of the things it is absolutely critical to understand about the history of Sweden (and Norway and Finland and, to an only slightly lesser extent, Denmark) is that it is very, very big and really doesn’t have a lot of people in it. That is still true today: relative to modern population densities, Sweden is pretty sparse. It is, give or take, about the same size as California but with about a quarter of the population, and a full half of that population lives in three cities. As soon as you get out of Stockholm and hit the commuter line to Uppsala, you’re into tiny towns, surrounded by fields, forests and moose (I saw a moose!). Beyond that, if for example your night train from Hamburg to Stockholm is cancelled at the last minute and you take an 18-hour bus journey instead, you’ll pass through miles and miles and miles of woodland and fields, dotted with lone farmsteads. Uppsala is a serious, old university city yet ten minutes from my accommodation I was running along a path looking out for otters that I’d been told live in the river.

Places matter to people anyway, but in very thinly populated landscapes, places can take on a deeper significance, that often ties together culture, politics, economics and religion. Gamla Uppsala was one of those places where people inscribed themselves - their ideas about identity, belonging, community and authority. It is a process that takes generations of polishing, reinscribing, burnishing with memories, traditions and physical landmarks.

Very close to Uppsala had been a burial ground, clearly for rich and powerful figures who were busried in boats and often with animal sacrifies, that dates from centuries before the Viking Age. Did people gathering in Gamla Uppsala in the 8th-11th centuries CE remember their names? Did their stories live on as legends, mixed in with magic and marvel? Or had the people of that distant past become transformed into the landscape features they left behind: rows of burial mounds that attracted their own tales?

We don’t know for sure but we do know that the people of Viking Age Sweden chose this place that had already been chosen before, because specialness attaches to places until it becomes magnetic, or charismatic. Nor do we know precisely what people did when they came to Gamla Uppsala. It would eventually become a political centre, a place for meeting and thrashing out alliances and laws. But it was clearly also a site for doing things that are harder to dig into the details of but that were clearly important.

For decades, archaeologists had known that the complex series of mounds and ridges at the site (much of Sweden is also very flat, so high things really stand out) had been used to create ceremonial ways for processions. My partner and I wandered around, thinking about this for the first time in the space: what would you be able to see if you entered the site here? How would your field of view suddenly open up as you stepped out from between these two hills? But more recently, scholars have discovered that the site was bigger and more complex than anybody had imagined. Cut trees had been used to create what look like paths or walkways of wooden posts stretching for miles beyond the site, creating paths through places of memory and meeting.

And, especially in regions where people might spend quite a lot of the year out in their village or homestead, and where the winters are still long and hard, big meetings might be for politics and ritual but they were also places where business was done and things were swapped and, probably, where young people got a chance to meet and dance and chat to somebody who wasn’t their brother or sister and re-think their perspectives on the opposite sex.

As we stomped around on the site site, imagining how it might all have looked in another evening of a long northern summer a thousand years ago, the light fading to the same clear, graphite grey we’d both noticed as we had travelled up Europe, the torches being lit, the sound of drums, shouts, tramping feet, perhaps the quiet then the noise that so often shapes group action, the past became real in different ways than it does with objects or books. They all play their part and we came away with a fresh understanding of those Vikings and their many contradictory identities.

Furry legs

As a bonus, if you’re now considering visiting Gamla Uppsala (which is an easy bus ride from Uppsala station), at the end of the main route through this incredible ceremonial landscape, there is also, a little, delightful historic farm where you can see buildings, tools and breeds of animal from Swedish farm life in the 18th and 19th centuries. Honestly, it was a bit disconcerting, given that we were still partially in a timewarp, but mainly what we took from it is that having short, furry (or feathery) legs is a major evolutionary advantage that far north! It was a truly splendid display of creatures with naturally occurring pantaloons.

The Uppsala we didn’t see

On that trip, we really didn’t see any of (New) Uppsala and now I know what we were missing (or saving for later). This week I’ve been thrilled to get a different perspective on the town. I was able to do so thanks to an invitation from Prof. Ingela Nilsson, a fellow Byzantinist, to come and talk about my research at the University and the main pleasure of this trip was having a chance to talk with colleagues. I also got to spend some time with the Keeper of the Coin Cabinet, Dr Ragnar Hedlund, who showed me some of the highlights of the collection as well as the University Museum.

Uppsala University was founded in 1477, so not my end of the Middle Ages, but one of the oldest universities in Sweden, along with Lund. Then it went through a bad patch with its funding (some things come and go!), before being effectively re-established by Gustav Adolphus, a Swedish emepror who (re)-established quite a lot of things, on account of being very successful militarily and therefore having a lot of wealth to spread about.

Perhaps the thing Uppsala University is most pround of intellectually is that Linnaeus (1707-1778), he who classified EVERYTHING, went there.

For me, one of the most exciting things was seeing an actual coin of the Danish colony in South India. That is going to get its own post one day, but in short summary it was one of the oddest bywaters of 19th-century European imperialism and consisted, much of the time, of a handful of Danish men living in a small fort just outside Pondicherry in Tamil Nadu trying not to hang out too much with the Indians (because that was not how empire was supposed to work in the 19th-century European mind) OR with the nearby French (in Pondicherry) or British (mainly in Madras, now Chrnnai), because they were rivals and enemies! That didn’t leave very much to do except wait for the next ship from Denmark to arrive. One of the longest gaps between ships was 21 years…

The colonists were so excited that they used put the name of the last ship to reach them on their coins instead of a date (as in, effectively, ‘this coin was struck in the period when the Good Ship Peter and Paul had visited last [and we have absolutely no idea how long it is going to be before we get to update these coins…]’). I’m still not completely sure what it was they bought or sold with those coins, either, or if they were just produced for something to do and to facilitate playing cards with one another, which was presumably also something to do.

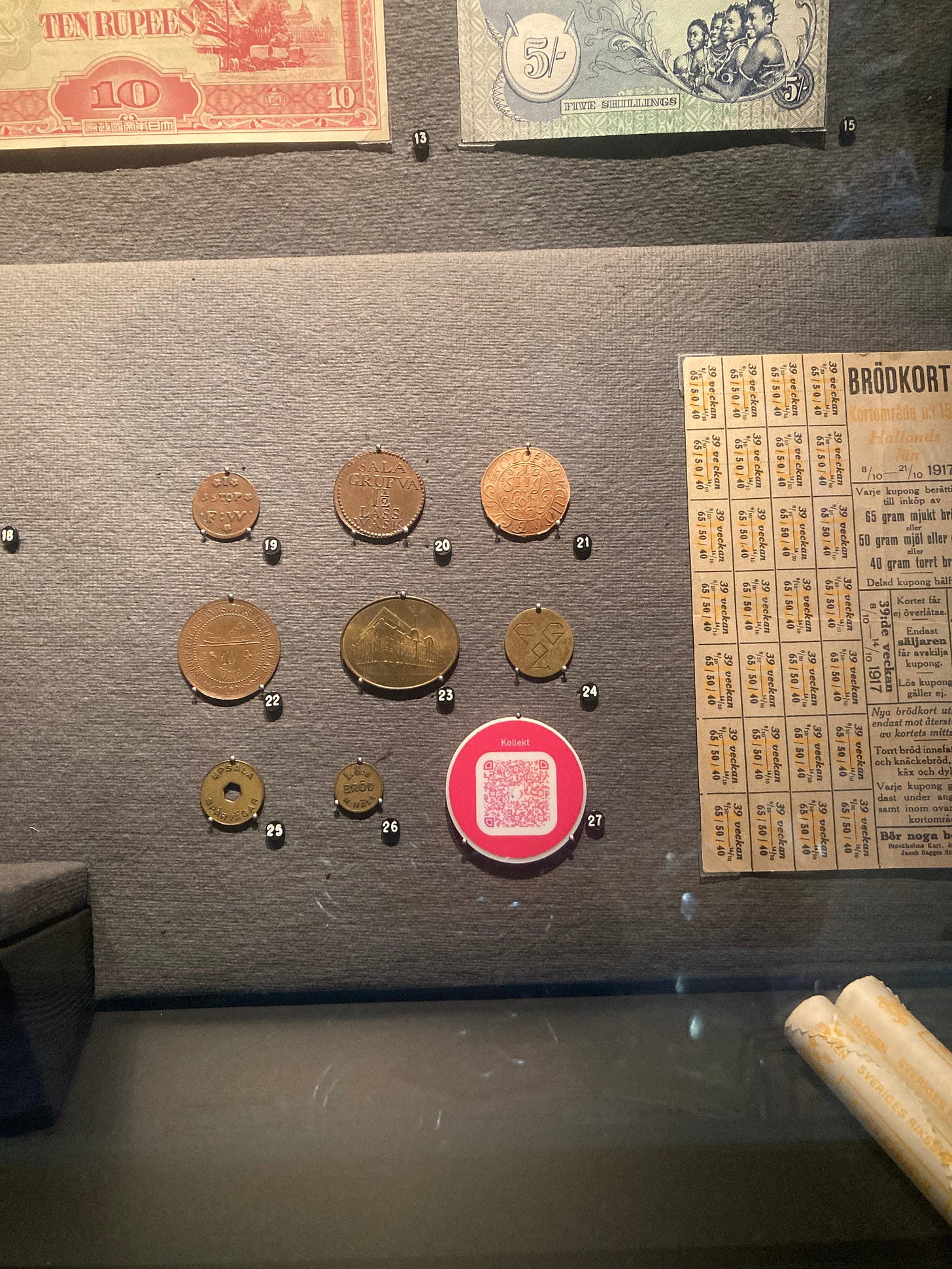

The Coin Cabinet also has a wonderful museum space with a gallery displaying aspects of the collection, including that round pink and white thing in the picture below, which is… a collection token from a local church. Hardly anybody carries cash in Sweden these days, so these tokens get passed around in the collection basket, like the traditional donation ritual in reverse: congregants take one of these out of the collection basket and they can then use the QR code to make an electronic donation.

Still to come, when I’m feeling nostalgic for Uppsala or numismatics or both: a story of blood money and rebellion; the amazing Augsburg Cabinet; an anatomy hall but for now I sign this off at the end of a journey many a Viking might just have recognised: from Swedish sunshine to the rolling hills of West Yorkshire. If you’ve ever looked at a map, those place names ending in things like -by (Wehterby), -l(e)y (Keighley) and -thorpe (Grimethorpe) are all th3e traces of Vikings past.