Hello,

Welcome and I hope you’re keeping well. I’m currently taking a break from caffeine, so turmeric latte for me with my history this month but that doesn’t make the past any less interesting.

Other people’s books

Recently, on the way back from Venice, a friend lent me a book. He’s also a medievalist and a great scholar so I rate his recommendations. Borrowing his copy was an added delight though because it turns out that my friend is an annotator! And I just love reading books with other people’s notes on them.

Whether you annotate your books or not is one of those ‘there are only two kinds of people in the world’ issues. I don’t but I sometimes wish I did. Reading my friend’s book was brilliant. I could see the bits he had found interesting or controversial. The parts with double underlining and a ‘?!?’ in the margins made me read back over them, wondering what he had seen that I hadn’t or enjoying our shared outrage at a silly statement. One of the most wonderful things about annotations is that they are usually made for the annotator not another reader so mostly it is a case of trying to figure out their train of thought, seeing where you have knowledge or interests in common, never being quite sure if you’re guessing right.

This was the book:

Why Empires Fall by Peter Heather and John Rapley, turned out to be a good read. Peter Heather is an early medievalist who works on the ‘barbarian’ conquests of the western Roman Empire in the 4th to 6th centuries. John Rapley is a historian of modern globalisation. I don’t agree with everything they have to say about the past, the present or the future, and nor did my friend, but I admire the courage of historians who are willing to stick their necks out about how the past might help the present and many of their points are sensible. If you are looking for two serious historians saying thoughtful things about today (well, actually, last year, and right now things change quickly!), Why Empires Fall is engagingly written, pretty short and worth a go.

That isn’t what I want to talk about here though.

How far is too far?

Whatever its politics, this book said something about distance that I found interesting. For the authors it was mainly a way to make comparisons between two very different periods in human history - the 3rd to 6th centuries in the Mediterranean and western Europe and the 18th century onwards at a global scale.

The point was that, if you want to compare the late Roman Empire with the modern globalised world, you have to understand distance as a function of time not space.

The Roman Empire was an immense place. It looks huge on the map, but you have to factor in, too, that everything in antiquity moved about twenty times less fast - at least overland: by foot, in carts, or on horseback - than now. The real measure of distance is how long it takes an actual person to get from A to B, not some arbitrary unit of measurement, so that the different localities of the Roman Empire were twenty times further apart in practice than they appear to the naked eye, and the whole Empire was actually twenty times as vast.1

This idea actually goes back a long way in modern studies of space, maps and geography. It began with another scholar of the Roman world, by the name of Bekker-Nilsson in 1988. In his ground-breaking study,

Bekker-Nielsen, Tønnes, ‘Terra Incognita: The Subjective Geography of the Roman Empire’, in Studies in Ancient History and Numismatics Presented to Rudi Thomsen, ed. by Erik Christiansen, Erik Hallager, and Aksel Damsgard-Madsen (Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 1988), pp. 148–61

he made the observation that, in the few Roman maps that we have and in texts talking about travel (of which we have a lot more), places were often presented as closer to one another if you could get between them more quickly than places that were geographically nearer, as the crow flies. This was because, he argued, the Romans were not crows (editorial licence: there is no actual mention of crows in the chapter). A place that was a couple of hours away along a navigable river or coast might feel as close as somewhere that was a couple of hours away along a good Roman road, or a couple of hours away along a dirt track over a steep hill but the actual distances would be very different.

Water transport was a lot faster than land transport and, perhaps equally importantly, the speed of water transport did not increase if you increased the amount you were moving. A man on a series of fast horses, with a good road, in decent weather - say a postal worker carrying an urgent letter about an upstart claiming to be emperor on the norther border - might be able to move across land as fast as a ship, maybe even a little faster over short distances or if the winds and currents were wrong for the ship. However, for a farmer or merchant with tonnes of goods or an army with supplies - weapons, tents, food, tools and all of the other things armies carry - travel by ox cart was much slower:

The fastest ever speed clocked by a racehorse was (apparently - I’m not really into horse racing) by Mr Frisk in the Grand National in 1990, at 35.6 miles per hour (57.2 kilometres per hour for those of you watching in decimal).2 But you can’t ride a horse like that for very long. The Grand National course length is about 4 miles (6.5 km). Over longer distances, a horse can maintain around 10 miles per hour (16 kph) for around 10-15 miles, or at least that is what the Pony Express worked out in the USA in 1860. The Pony Express was a relay mail service that, by using regular changes of fast horses and riding day and night, could get a letter from St Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, California, or 1966 miles, in just 10 days. Many large ancient empires, including the Roman Empire, seem to have had some sort of system like this, with regular way stations, well-fed, fast horses and specially trained riders, but only the most important imperial mail could be sent that way. For even a rich person with access to their own horse, 20-25 miles per day would be a good pace and if they wanted to send anything heavy or over rough terrain, that number starts to drop sharply.

Ox carts, which would have carried most bulk goods, can move around 3-4 mph (5-6ish kph) on a fairly flat road or decent track and can’t really make much headway over rough or hilly terrain at all.

The variables for boats are enormous and depend on things like whether it is powered by oars or sails, is moving with or against winds or currents, its hull shape and a bunch of other things, but for the sake of orders of magnitude, the fastest ever recorded speed by a sail boat was 68 mph (109 kph), apparently by a boat by the appropriate name of Sailrocket, but a more usual speed would be somewhere between 6 and 20 mph (9-32 kph). The big difference if you are a farmer, army supplier or anybody else dealing with a lot of stuff is that, to a certain point (i.e. how big is your boat?) this speed won’t be affected very much by how large or heavy the cargo is whereas every added pound/kilo on an ox cart makes life harder for the oxen and harder to do things like heave the cart over ruts in the road or the occasional hill.

This can lead to the stereotype that land transport was so pointlessly slow, awful and expensive that life could hardly go on anywhere in the ancient or medieval world that wasn’t right on a sea or a river, which is weird when you consider how many roads the Romans built! And in fact, this has been shown to be an exaggeration: land and water transport worked together in the Roman Empire and, probably, most everywhere else, too.3

Still, if we take that two-hour journey time that I started with, you, as a villager in the ancient or medieval world, might reasonably feel that the village that was about a two-hour walk away on a good, flat path (about 8 miles or 12 kilometres), the market town along a hilly road that you took your ox cart two hours to every week (about 5 miles or 8 kilometres) and the city about a two-hour sail along the coast (35 miles or 56 kilometres) were all roughly as far away from you as each other. After all, it would take you about as long to reach them all.

Bekker-Nilsson’s argument made a splash and since then people have looked differently at space, travel and distance in all sorts of places and times, in fact pretty much anywhere before the arrival of planes, trains and automobiles.

In reality, it applies quite well in the modern world, too, though people often don’t because of a general tendency to see the present and the distant past as radically different from each other. But a lot of the conversations going on in the UK now about how it is easier (i.e. quicker) to get by rail or road from Leeds or Manchester, both in the north of England, to London in the south, than it is to get between Leeds and Manchester, are tapping into the same phenomenon. Most people know that Leeds and Manchester are geographically closer together than either are to London but in practice, because it is easier to get to London, London is often where it seems easier (and here, we also mean cheaper) to do business, to be part of professional associations, to go to the theatre, etc.

This modern parallel is worth making because it acts as a counterbalance to a very predictable but very peculiar way in which debates about space, distance and time in the ancient world developed after Bekker-Nilsson. Because what happened next was that some people began suggesting that folks in ancient and medieval times weren’t capable of understanding that absolute distance and the time it took to travel a distance were different. They could only imagine the world in terms of how quickly you could get to things.

This is now a loop I’ve learned to recognise but it has taken me nearly twenty years to see it for what it is, every single time: nonsense.

It is definitely true that there were differences in how people understood the world in the past. (And there are differences today in how people understand the world!) Fewer people were educated in the past and the limits on our collective knowledge were greater, especially in areas like science and technology. People in the Middle Ages did not think about things being made of atoms or know how electricity or germs worked, but these are differences in knowledge not intelligence or imagination. We actually know very little about what most people thought, or how, but there is no scientific reason to think that people were cognitively less capable than we are. When we have evidence for people thinking hard and creatively, boy were they good at it, sometimes. Sometimes they were mediocre at it. Sometimes they just said random stuff that could be pretty silly. So… a lot like now. They often chose to think about different things than us but that, again, is about knowledge, fashion and choice. (I sometimes wonder what people in the future will think we were absurd or idiotic for thinking about, or if they might be more charitable.)

So, having set aside the nonsense, people in the ancient and medieval world were completely capable of understanding absolute distance. We know this because sometimes they spent a lot of time working it out. They also knew that how long it took to get somewhere, and indeed, what reasons there might be to do that, changed how close somewhere felt in all sorts of ways.

This could also be a matter of cognitive/emotional distance rather than either absolute distance or journey time: in other words, people in the Middle Ages were fully capable of thinking about how far away things were in terms of miles, or stades, or li or whatever mathematical units they preferred. They were also fully capable of thinking about how far away things were in terms of low long it took to get there. And they were capable of thinking about how far away things felt or seemed.

There is a selection of texts that I absolutely love for seeing people doing all of these things. They were pieces of writing about how to move through real space but written for people who were never meant to. They were designed to help people imagine places they would never go, in order to help them feel close to a place.

These texts began to be written in the 4th century and continued through the Middle Ages. They were produced in western Europe and were all about a space that was taking shape in their imagination: what came to be called ‘the Holy Land’.

This was the collection of places where the events of the Bible were believed to have taken place. At its centre was Jerusalem, but it also included places like Bethlehem and Nazareth (the birthplace of Jesus and the place his family lived and he grew up, respectively). It could stretch as far as Egypt, where various events of the Old Testament took place, but mainly it referred to the area around the River Jordan. Places in it could be linked to the Bible but also to famous saints and stories linked to the events of the Bible by more local, informal traditions.

The earliest of these pieces of writing that survives is by a woman who lived and travelled in the 4th century CE. She is usually known as Egeria (pronounced, at least if you’re planning to drop her into conversation in English, e-JEH-ria), or Etheria, and may have come from the area that is now modern Spain. She wrote about a journey that she made in the early 380s CE and the account is written after her travels to a group of women. She calls them her ‘sisters’, and there is some disagreement about whether this means biological siblings (generally not thought most likely), fellow nuns (possible and for a long time assumed, but actually this would be pretty early in the history of Mediterranean monasticism and anyway, she doesn’t say much else that sounds that nun-like) or just a community of friends and acquaintances who were also Christian, since early Christians often addressed each other as ‘brother’ or ‘sister’. This latter seems to me the most convincing explanation. Clearly, though, as the text was later copied at least a couple of times, other people, centuries later, also found her account interesting.

Her itinerary was long and detailed and I won’t go through it all here. You can read the full text in translation here. But what I would like to do is to pick out examples of Egeria thinking about distance in different ways.

We don’t have the beginning of the text, so we leap right in when Egeria is on the approach to Mount Sinai.

Now on reaching that spot, the holy guides who were with us told us, saying, “The custom is that prayer should be made by those who arrive here, when from this place the mount of God is first seen.” And this we did. The whole distance from that place to the mount of God was about four miles across the aforesaid great valley. For that valley is indeed very great, lying under the slope of the mount of God, and measuring, as far as we could judge by our sight, or as they told us, about sixteen miles in length, but they called its breadth four miles. (Chapter 1)

The travellers reach a small monastery near the foot of what, Egeria goes on to explain, turns out not to be just one mountain but a whole cluster of mountains that are, nevertheless, all referred to as the mount of God. From there,

early on the Lord’s day, together with the priest and the monks who dwelt there, we began the ascent of the mountains one by one. These mountains are ascended with infinite toil, for you cannot go up gently by a spiral track, as we say snail-shell wise, but you climb straight up the whole way, as if up a wall, and you must come down each mountain until you reach the very foot of the middle one, which is specially called Sinai. By this way, then, at the bidding of Chris our God, and helped by the prayers of the holy men who accompanied us, we arrived at the fourth hour, at the summit of Sinai, the holy mountain of God, where the law was given, that is at the place where the Glory of the Lord descended on the day when the mountain smoked.

So, here we have distance as time - around four hours of pretty hard walking, since the hours were counted from dawn in usual Roman convention. The party did not get back down the mountain until the tenth hour and took a different route on their descent so as to see more of the holy sites. And throughout it all, Egeria lists the many things they saw, all in terms of the stories of the Bible. Around Sinai, these are Old Testament stories, so we have the place where the golden calf was built and the people danced in front of it (apparently, she says, the rock on which it stood is still visible), the campsites of the Israelites while they wandered in the desert, the place called ‘Burning’, because once part of the camp of the Israelites caught on fire but when Moses prayed the fire stopped. If these stories aren’t all (or at all!) familiar to you, you are not alone. Some of them are the big stories of the Christian tradition, like the idolatry to the golden calf, but others, like the fire in the campsite, are pretty minor events in terms of how the Old Testament stories are generally told.

What comes across throughout the text of Egeria is that other, emotional or cognitive closeness or distance. From the top of Sinai she says they could see

Egypt and Palestine, and the Red Sea and the Parthenian Sea, which leads to Alexandria and the boundless territories of the Saracens…

Evidently, the ‘boundless' territories of the Saracens, which in the 4th century would have referred to groups of desert dwellers outside formal Roman control are outside her mental imagination. Other places, though, she asks the guides to show her or talks about with only fleeting references to the texts, knowing that her readers will know what she means. In each place, she says, she insists that they read the relevant part of the Bible. And this is where some of the purpose of the text becomes visible. She moves quite quickly through the biblical references but often dwells on seemingly minor details - the rounded edge of the rock on which the golden calf stood, the little fruit trees that the monks tend around the foot of the mountain. And then she says,

Now it would be too much to write of all of these things one by one, for so great a number could not be remembered, but when your affection shall read the holy Books of Moses, it will more quickly recognise the things that were done in that place.

This is a slightly awkward formulation that was common at the time and might be rendered ‘when you read the holy books with proper affection you will be able to fill in the gaps from what I have told you about and imagine the things I didn’t have time to tell you about because they were happening nearby.

A lot of work has been done on this text and others like it, written in later centuries. At first they were imagined as tour guides or even instruction manuals but that idea was eventually rejected. They just aren’t detailed enough about the things you would actually need to know to make this kind of journey yourself at the time: how much, exactly, should a camel ride back from Sinai towards Jerusalem cost? What foods are and aren’t good to eat if you’re coming from Spain, or wherever else the author was? What language do any of the people you’re going to meet speak and will you need to hire an interpreter? The list of things these texts don’t tell you about actually travelling is pretty long!

Instead, the common view now is that they were all about that audience back home. In fact, some of these texts (though probably not Egeria) are not even thought to have been real accounts of real journeys. Instead, some of them appear to be made up - a fictional ‘pilgrim’ has a story put together around them, cobbling together details from Egeria and other writers like her. A dead giveaway is when two places appear in a text that claims to be of the same journey but we know that descriptions of two different sites date from different times because of how they are described. What is left in or left out can also be a clue: sure you might leave stuff out, as Egeria does, but sometimes texts miss out things that surely nobody who was actually there would skip. Instead, the choice of which places get into the story seems to be connected with debates in the place where the supposed pilgrim came from, for example about what made a good Christian king or how best to interpret the bible.

Whether these journeys were all real, though, can also be separated from how they worked in the minds of their readers. As we’ve learned more about how people in the Middle Ages in Europe read, including the different functions of group reading, reading aloud, private reading, meditation on reading, reading as prayer, etc., it seems more and more likely that these texts were imagined as journeys of the mind. they were different way of reading the familiar texts of the Bible, adding new layers of richness and life to the stories. That is why they so often contain details about the sounds, sights, textures and physicality of the landscape. The idea of going on pilgrimage to the Levant for Christians, today as in the Middle Ages, is to get closer to God by being in the spaces where God acted directly in the world, through the events of the Old Testament and the incarnation of Jesus. The idea of reading one of these texts, in a time in which most people could never have made such a journey, was to become familiar with those places in another way, to make them feel close and so to feel closer to God.

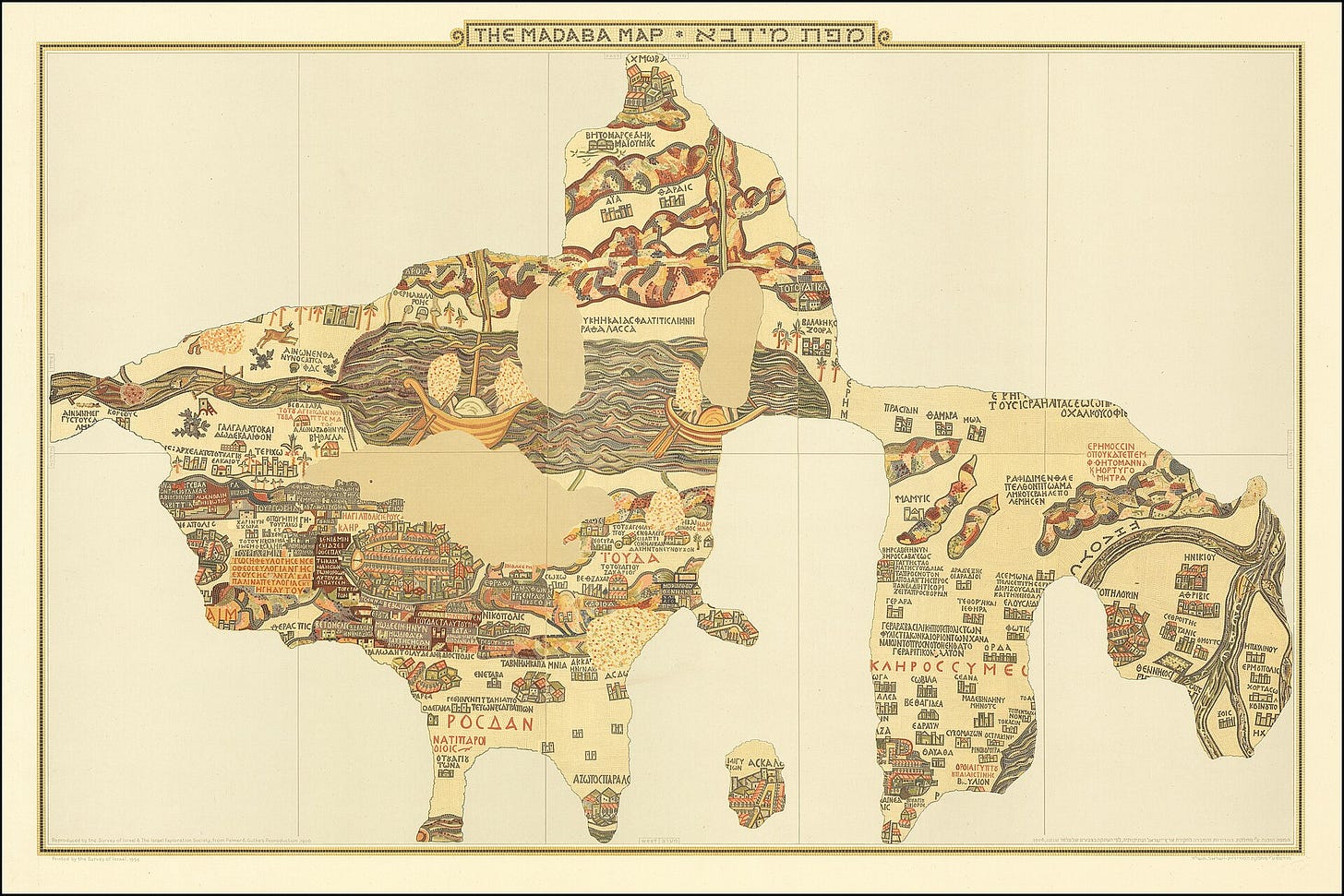

In a place called Madaba, in modern Jordan, there is a huge mosaic map made in the 6th century, so some time after Egeria, but in quite a similar East Mediterranean - the Romans were still in charge, Christianity was by now the majority and dominant religion, which was getting to be the case when Egeria travelled. There would have been more churches but a similar amount of imperial infrastructure for travel, like roads and harbours. The mosaic is amazing and there is nothing like it anywhere else:

It isn’t intact but here is what the remaining sections look like altogether:

This reconstruction is very helpful for seeing the thing as a whole but the most interesting thing about it when you are actually in Madaba is that… you can’t. Perhaps, if you were a 6th-century woman and up in the first-floor gallery that was often where women attended church services, you may have been able to see it all laid out below you, but even then, probably not. There would have been people on it, at least in later centuries, we know there was furniture on it. And it would have been easier to see the whole layout but impossible from up there to read the labels on all of the places or see the details in the scenes. This was a map that was meant to be seen from the ground, but from the ground you would never be able to see it all.

It is also a representation of the Holy Land, like Egeria’s travel guide and the most widely accepted theory for how it was meant to be used was as another tool for mental contemplation and feeling closer to the events of the Bible and therefore to God. Whether people were led around it, perhaps during specific holidays and festivals, or took themselves on a mini-pilgrimage from place to place on it, it seems to have served some of the same purpose as Egeria’s text: it gave texture, imagery and physical space to stories.

The scenes depicted in it are accurate enough that a traveller could use them to imagine places they had seen or perhaps ones they hadn’t. (The people of Madaba lived in the Holy Land and quite close to Jerusalem, so for them visiting the holy places was not necessarily a once-in-a-lifetime affair but they still couldn’t do it every day.)

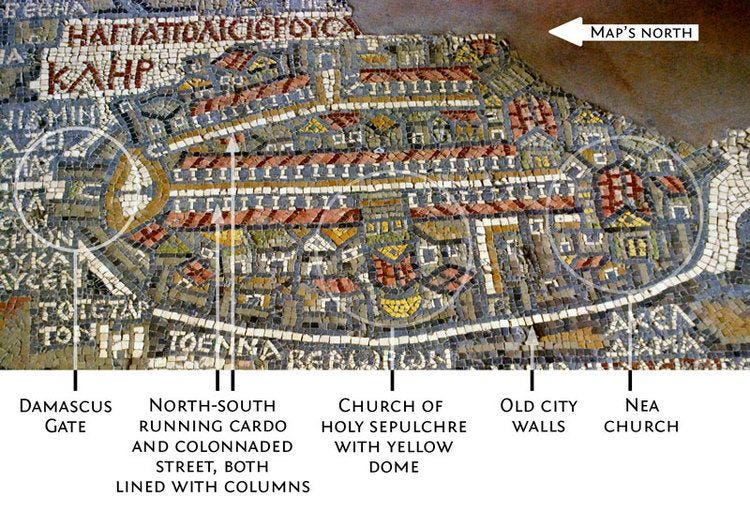

If you aren’t immediately familiar with 6th-century Jerusalem (though surely that cannot be!), here’s a handy annotated copy:

I started reading Why Empires Fall on a train from my friend’s town to Milan, on my way home. Since 2019 I haven’t flown in Europe and learning the art (and sometimes the messy finger painting) of what is often termed ‘slow travel’ on trendy travel blogs has made me think in different ways with texts like Egeria’s and the Madaba Map, to appreciate those different ways of understanding space and time and feeling as a common thread I share with the people I read.

When I first went to Italy by train and bus, in 2017, it seemed a long way to go, a long time to take and massive amount of (very rewarding) hassle. I’ve done it quite a few times now. I’ve also been further and to places with much less good rail networks. (I will take every opportunity to say this because it often gets a bad rep internationally: the Italian rail system is FANTASTIC!) In a couple of weeks I’m off to Amalfi, in southern Italy. It should take just under 36 hours, door to door and I’m looking forward to it, in a relaxed sort of way. I’ve got the pictures in my mind that Egeria paints, of how the landscapes look, and of the main cities I’ll go through. I may be modern but I honestly don’t know how far Amalfi is from me as the crow flies. (Like the Romans, I am not a crow.) But I do know how long it takes to get there. And, because know what to expect, it doesn’t feel all that far. Because real distance has never been simple.

Why Empires Fall, p. 17.

If you are not reading this from Britain (and possibly even if you are!), ‘For those of you watching in…’ is an in-joke reference to a famous ‘oops’ moment in the history of modern television. Back in the days when colour televisions were taking over the UK but had not yet conquered the market, a prominent snooker commentator, Ted Lowe, was describing the layout of the table before a player took a shot. He suddenly remembered that many of his viewers might still be using older technology and helpfully added, ‘For those of you watching in black and white, the pink is next to the green’.

Laurence, Ray, ‘Land Transport in Roman Italy: Costs, Practice and the Economy’, in Trade, Traders and the Ancient City, ed. by Helen Parkins and Christopher Smith (Routledge, 1998), pp. 129–48