Mirror, Mirror on the wall...

...who is the fairest (agrarian tax-raising imperial superstate) of them all?

Hello,

Welcome (back), grab a beverage of your choice and let me take you back in time. The first centuries BCE and CE were an ‘Age of Empires’…

Don’t worry too much for now about how it got that way. That might be a future coffee or ten: it is certainly a hatful of amazing stories! Instead, just picture Afro-Eurasia and a chain of massive states strung across it, most of them covering the area of several modern nations, all of them containing people of many different communities, religions, languages and cultures.

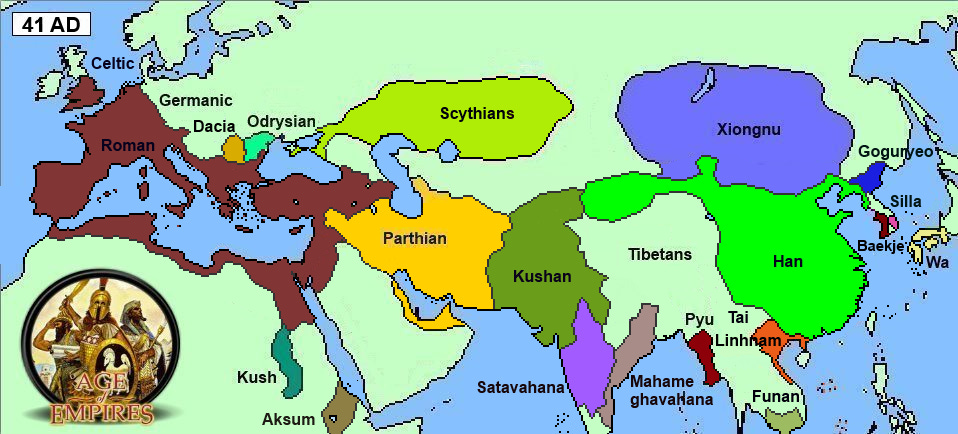

Each of them commanded one or more major river systems, which provided (thanks to the taxed labour of millions of peasant farmers, who didn’t have much say in the matter) surplus food to support armies and cities and imperial courts. In East Asia the Han Empire controlled the Huang, Yellow and Yangtze rivers. In Central Asia and northern South Asia, the Kushan Empire controlled the Amu Darya and Oxus rivers and parts of the Indus River system. In central South Asia, the Satavahanas (whose purple bit on the map above probably, at least sometimes, extended right to the east coast of the peninsular) commanded the Krishna and Godavari rivers and, sometimes, large parts of the Indus and Ganges systems. In West Asia, the Parthian Empire dominated the Tigris and Euphrates. And the Roman Empire controlled the whole coast of the Mediterranean, which meant they ruled the River Nile in Egypt.

What we know about each of these empires has increased over decades and centuries. We can piece together their worlds from buildings and coins and things they carved on walls, from latrines and kitchen scraps, even from the bones and burial patterns of emperors and their subjects. But what they thought about each other can also be enormously illuminating, if we realise which way the light is pointing…

Histories of Empire, Imperial Histories

East Asia is quite remarkable for having a pretty continuous set of ‘official’ histories, documenting the political life of the various imperial dynasties that have ruled huge areas around the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers (though at times far beyond). What makes a history ‘official’? It isn’t an easy question to answer but when people talk about the imperial histories, or dynastic histories, in East Asia, they generally mean things like:

They were written by people employed and working at one or other imperial court, often at the request of the emperor or as part of the expected functions of the court bureaucracy.

As a result of being written at imperial courts, these histories usually had access to original documents and eye witnesses to the things they were writing about. Want to write about that battle that happened 30 years ago? Ask the general who was there, or read some of the reports sent back from the front line to the capital to let the emperor know how it was going! That gives the histories an ‘official’ feel in the sense that they are telling the story from inside the centres of power.

They are also ‘official’ in the sense that they tell the story that those centres of power wanted told. Often a new history would be commissioned when a new dynasty came to power, in order to explain how they had risen, legitimately and gloriously, to replace the one before, which had, in turn, started gloriously but then become awful, thereby justifying its replacement. This means that the histories all have quite a similar story arc, but also that they kept getting longer, since each one often started from ‘the beginning’ (usually defined as the Qin Empire of the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, but with some longer, semi-legendary histories going way back before that).

The histories have also been critical in defining what officially is ‘China’. The histories mostly start when the Qin Empire conquered a very large area of continental East Asia, but not by any means the exact area that is China now or has been China at various times in the past. But, in periods when dynasties, like the Qin, were overtaken by dynasties each ruling smaller parts of that older state, each court would use their official histories to explain why they were the ‘true’ successor to the sole role of top emperor, inheritor of that emperor before who had ruled the bigger area, and therefore, rightful ruler of all of that area. New neighbours and rivals would be depicted as illegitimate rebels or minor break-away regimes that would, eventually, be brought back together. When one court did manage to rule as large an area as some of the biggest empires of the past, their official histories would explain how they had ‘reunified’ that earlier empire.

And, perhaps most important for us as scholars hundreds or thousands of years later (since these official histories go back around 2000 years), these histories were ‘official’ in the sense that they got preserved. Each court had its library and its archive and these histories were part of them. Some of them did not survive, by chance or because they were destroyed so that one ‘official’ history could replace another, but some of them did and, because they were all using many of the same earlier histories to lay claim to the same collective past, that means we can often reconstruct even parts that have gone.

Scholars of the official histories of East Asia are therefore able to work with a dense web of interconnected, detailed accounts of the past, with a direct line to political archives and a record of how people’s idea of their own story grew and changed over time.

For somebody who trained in European and Byzantine history and now works a lot on South Asia, the East Asian imperial sources are an astonishing and also quite intimidating body of material. I’m extremely conscious of relying on translations and trying to get my head around whole worlds of knowledge about how these sources were made and preserved. Still, I love reading them. No matter how steep the learning curve, and however much I will always mooch around the bottom of that curve as an interested non-specialist, I am grateful for the scholars who produce translations and write about the complexities of these sources in ways that people from other fields can understand. Why?

Because, original sources are the best chance we have of engaging on their own terms with the people of the past: how they understood and described their world and what that tells us about being them, or what they thought of each other.

The weird and (improbably) wonderful world of the Roman Empire

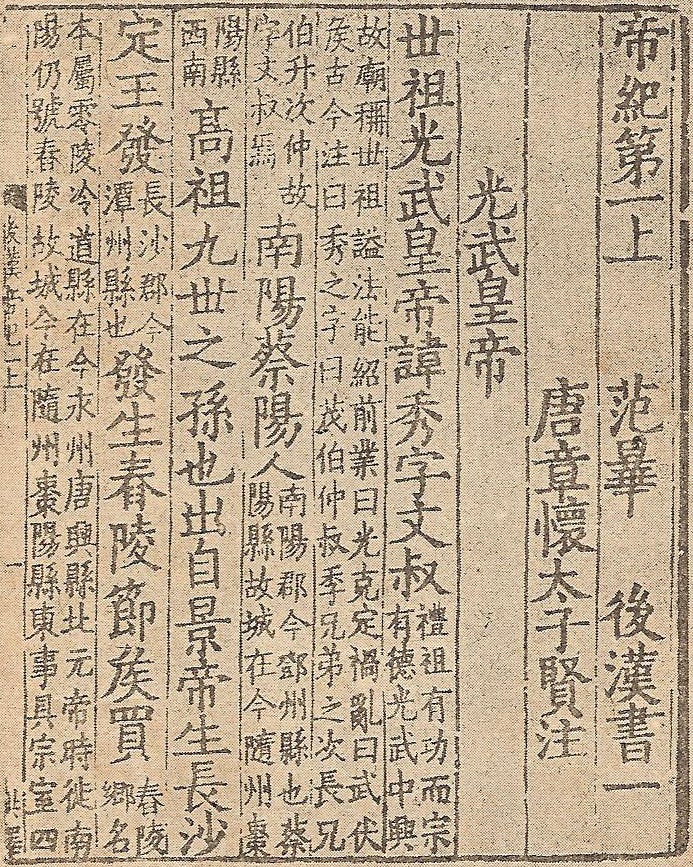

Recently I re-read a passage I first found many years ago from a particular official history known as the Hou Han Shu or Book of the Later Han. It was written in the 5th century CE at the court of a dynasty known as the Liu-Song, who ruled the northeastern coastal region of what is now China. Like all such histories, it looked back to earlier centuries and used older sources to speak of them. It was, in turn, used extensively by later historians writing court histories in Chinese.

The part I was interested in, when I first looked at the Hou Han Shu, was what it showed that somebody in the 5th century in East Asia thought they knew about the coinage and economy of the Roman Empire in the 1st century CE. It was this:

They make coins of gold and silver. Ten units of silver are worth one of gold.

It is fascinating.

It’s not accurate. But it’s not nonsense.

The Roman Empire in the first century CE did make coins out of gold and silver (and various copper alloys) and the relationship between the value of gold and silver was complicated, variable and often a lot more than 10:1. BUT between 10:1 and 20:1 ratios seem to hover around the general relative value of gold and silver in the Mediterranean/West Asia across the broad sweep of ancient and medieval history (and here I am being very vague here, but I think that is okay, because so is this source!). The figures are wrong or, at least, extremely guesstimate-y, but they aren’t wildly off base (unlike, say, the idea, also found in first-millennium CE imperial histories from East Asia, that people in the far west of the world had their babies delivered by storks).

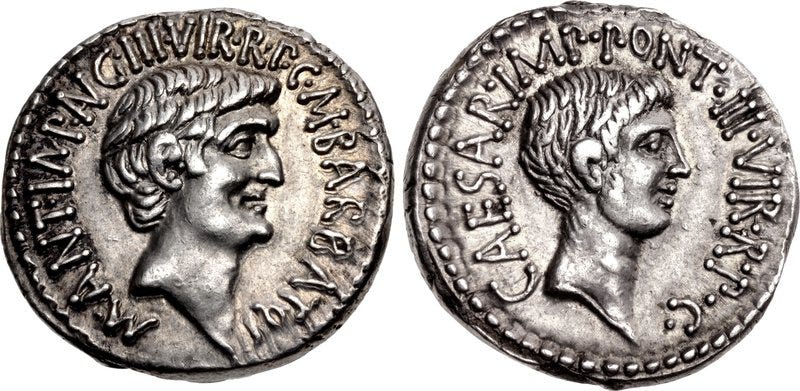

In addition, at this time the Liu-Song and other East Asian states mostly only issued coins made of copper alloy, so saying that the Roman Empire used different metals was registering a difference, not just making the assumption that it worked like they did. There was some information moving, possibly even in the form of gold and silver coins of the first century, which are very rarely found in East Asia. Still, it struck me as an oddly spare description and oddly lacking in some things that might have seemed obvious, especially if somebody actually had a coin or two to hand. For example, other differences include:

Roman coins having pictures on them (East Asian coins had only text)

Roman coins having Latin inscriptions on them (or at least, having inscriptions on them that were clearly in a very different writing system)

Roman coins NOT having a square hole in the middle of them. That is pretty much the first thing that anybody notices when they compare traditional East Asian to traditional West Asian coins, no matter whether they care about numismatics or not.

As is usually the case, though, reading something out of context and reading it in context are two different things. That single line about what somebody in 5th century CE East Asia thought about 1st century CE coinage comes as part of a more general discussion about life in the Roman Empire of the first century CE. (The Roman Empire was called in Chinese 大秦, which is written Ta-ts’in using the transliteration system preferred by Hirth, who made the translation I’m using in 1885. In modern pinyin, it is written Daqin):

Their [i.e. the Roman’s] kings are not permanent rulers, but they appoint men of merit. When a severe calamity visits the country, or untimely rain-storms, the king is deposed and replaced by another. The one relieved from his duties submits to his degradation without a murmur. The inhabitants of that country are tall and well-proportioned, somewhat like the Chinese [people of the Middle Kingdom], whence they are called Ta-ts’in. The country contains much gold, silver, and rare precious stones, espcially the “jewel that shines at night,” “the moonshine pearl,” the hsieh-chi-hsi, corals, amber, glass, lang-kan [a kind of coral], chu-tan [cinnabar?], green jadestone [ching-pi], gold-embroidered rugs and thin silk-cloth of various colours. They make gold-coloured cloth and asbestos cloth. They further have “fine cloth,” also called Shui-yang-ts’ui [i.e down of the water-sheep]; it is made from the cocoons of silk-worms. They collect all kinds of fragrant substances, the juice of which they boil into su-ho (storax). All the rare gems of other foreign countries come from there. They make coins of gold and silver. Ten units of silver are worth one of gold. They traffic by sea with An-hsi [Parthia] and T’ien-chu [India], the profit of which trade is tenfold. They are honest in their transactions, and there are no double prices. Cereals are always cheap. The budget is based on a well-filled treasury. When the embassies of neighbouring countries come to their frontier, they are driven by post to the capital, and, on arrival, are presented with golden money.1

There is a lot here, I know, so let’s break it down a bit. First of all, when this account was written in the 5th century CE, it was already re-using older material. If the information feels like lots of things stitched together, that is very common of the imperial histories, which very often were stitched together out of existing material. It would be excerpted or commented on or added to but it was also preserved by being copied out so as not to lose potentially valuable older information: there was always a balancing act going on, that is familiar to every historian, between keeping everything and trying to tell a coherent story.

Loosely, though, we could divide this description into two different sets of information:

what do we [i.e. the people of East Asia] get from the Roman Empire?

what is life like in the Roman Empire?

Both sets of information reflect the imperial court perspective of the source. The goods it mentions would all have been rare, costly, luxury items, not least because moving anything from the Mediterranean to East Asia in the first century CE would have been very hard, time-consuming and expensive. Only high-value and low-bulk, easy-to-move goods would have made the cut and the people at the other end who could afford them were, of course, emperors and their courtiers. So, the tangible connection they had to the Roman Empire was things like jewels, perfumes, gold and silver, fancy cloth and asbestos. The East Asian sources show a definite excitement about asbestos: it was an intriguing novelty from the west. One of the ways that elites could show off, and believed that Roman emperors must show off, was by having napkins made out of asbestos to wipe their hands on after a meal then throwing them into the fire to clean them, presumably to the delight and awe of their assembled guests when the napkin was pulled out of the flames, fresh and like new! (And honestly, who wouldn’t, if you could? And if we didn’t know how dangerous asbestos is.)

The ‘what was life like’ stuff, which forms the beginning and end of the account, is also concerned with the sorts of things that rulers tend to care about: tax, politics, diplomacy. But how accurate are either of these sections?

The ‘stuff’ bit is complicated by how hard it is to understand many of the technical terms, but broadly, it is reasonable. Not everything on the list came from the Roman Empire, but it all came from areas far west of the Liu-Song territory. Exactly where the Roman Empire started and finished wasn’t exactly easy even for the Roman Empire to keep track of, so was at best a rough idea from way over in the Liu-Song Empire. Besides, by the time all those goodies reached them, they were probably all being carried together and might all have been labelled ‘Roman’ by merchants, if that got them a better price or more interested buyers. So the ‘stuff’ is a bit hazy but not unexpectedly so, considering.

The politics are… weirder. You can see where some of it is coming from.

The Romans did trade with India.

Treating diplomats well was something most ancient empires did, as it was one of the only ways to be sure that your other world-empire neighbours knew how rich and awesome you were, so that detail is both largely correct and would, in any case, have been a plausible guess for the author to have made.

Even the bit about emperors being chosen makes a kind of sense: East Asian dynasties were… well, dynasties. They emphasised biological succession through the male line, except when they didn’t, but even the exceptions were justified in dynastic terms. Either a dynasty had become useless and so had to be replaced by a new one, or particular circumstances meant somebody else had to be in charge for a bit, e.g. to protect the rightful (biological) heir to the throne while they were a child. The Roman Empire did not have hereditary succession. Sometimes sons succeeded fathers but this was not ‘policy’ and lots of political theorists in the empire thought it was probably a bad idea. Emperors might also adopt their chosen successor as a son, but these were usually adult men being adopted by another adult man, so the idea of ‘family’ was very visibly a political mechanism not an endorsement of a particular gene-cluster.

Nevertheless, there is something decidedly odd about this description of the Roman Empire. It is how nice it sounds. Deposed emperors didn’t mind (and they certainly didn’t kick up a fuss by starting a civil war or assasinating people or anything like that)! People didn’t lie or cheat or over-charge! The granaries and the treasuries were always full! Doesn’t it all sound like a bit of a paradise? And believe me (if reading about the Roman Empire is not already your thing), if you dive into the sources left to us from the Roman Empire, however admiring or otherwise you may be, ‘nice’ and ‘paradise’ are unlikely to be words that spring to mind.

Telling the emperor his bum is showing (and keeping your head)

Of course, one of the first things to ask when reading anything is who it was written for (as well as who by and when and why…). In the case of the East Asian court histories the ‘who’ is fairly straightforward, at least in broad outline. (Nothing is really straightforward once you look closely.)

They were written for the court that paid for them to be written. They were intended to explain how the stage was set for the ruling dynasty to take power, to justify that power, to record the dynasty’s glorious deeds and glorious denizens, and, usually, to compile potentially useful knowledge about the world along the way. They were not, however, written by those mighty dynasts themselves. They were written by scholars who, in order to be able to gather and understand older documents and turn them into new records, needed training. Luckily we also know quite a bit about what that involved. They would have learned to compose poetry and letters, to read and memorise and debate the philsophical, legal and political texts that underpinned most East Asian empires of the first millenium CE. Confucius is the most famous today but the curriculum was quite broad and included opposing perspectives on various matters, meaning that people had to learn to weigh up arguments, make their own and explain why. Scholars in training and then on the job would have spent time in the archives and studying the earlier histories.

Presumably, lots of people in ancient empires, as today, had all sorts of views about how people at the top were managing things, and not all of those were good. But in ancient East Asia, court scholars were the people who had the best chance to try to communicate some of that to their masters and, perhaps, to posterity, while hoping to survive the experience. For that, the Roman Empire was extremely valuable. It held a special place in the imagination. (So did the Seres, as the Romans called the people of East Asia, in the Roman imagination: they thought of the Seres as refined, sophisticated and having sheep that grew on trees.) Rome was thought of as a great empire, a kind of ‘western Middle Kingdom’, counterbalancing the great power in the east. It was too far away to be any kind of threat or even a distraction, but that could make it something else: a mirror.

In the 5th century under the Liu-Song, for example, family relations were becoming strained (or at least, so we are told in later imperial histories that explain why, eventually, they had to go, replaced by better families… at least for a while). Sons would turn on fathers, it would be said of them, and the accusation of mass, forced and inter-generational incest makes an unlikely but ugly appearance in the charges levelled against them. Even if only a bit of this was true, might a critic at court have wondered what an empire might be like where the accident of birth didn’t get to decide who sat on the throne? And might the idea of a fabled, peacable Roman meritocracy have been a way to wave that idea under the noses of his fellow courtiers and even the emperor himself, or at least to leave a record to the future that people in the Liu-Song court were capable of considering other ways to govern?

War with neighbours also put huge strain on Liu-Song finances. Their treasuries were not full. Later accounts speak of fields stripped bare by enemy soldiers. Presumably, the granaries weren’t full either a lot of the time and, in famine, honest prices are usually one of the first things to go, even if East Asian governments, like Roman ones, sometimes tried to force people to stick to ‘honest’ prices. The impression of scarcity and struggle is even visible in the 5th-century coins of the Liu-Song. They follow a standard East Asian pattern but many are visibly thin, often so much so that small (unintentional) holes are visible in the main body of the coin, where the hot metal poured into the mould wasn’t quite enough even to fill the space. The intentional holes in the middle of them are also often huge, as if to try to save metal while still making a coin with the right diameter. And their alloy contains a lot of lead, which was often used by coin makers across the ancient and medieval world when other metals were scarce. It is heavy and abundant but is also usually considered of low value and makes coins brittle and difficult to use.

Perhaps the author knew the Roman Empire made its coins out of gold and silver but, if so, he probably knew a bunch of other things about them, too. He chose what to mention, and maybe that was because it would have made the best contrast with the slightly crummy coins paying his own salary. Who cared if they had pictures on or not? In its prosperity, its peacefulness, even its orderly politeness, the Roman Empire imagined in this extract from the Hou Han Shu looks less like the Roman Empire as it knew itself and much more like a suggestion that the local representatives of imperial power take a look in the mirror and consider their own wardrobe choices.

This translation is taken from Hirth, Friedrich, China and the Roman Orient: Researches into Their Ancient and Medieval Relations as Represented in Old Chinese Records, Reprint 1975 (Shanghai and Hong Kong, 1885) <https://archive.org/details/chinaandromanor01hirtgoog> [accessed 24 August 2017], p. 5. Hou Han Shu Ch. 88.27. It is an old translation and there have been subsequent debates especially about the terms for different products from the Roman Empire. However, this is the translation I have ready access to (and which you can too, via the good offices of archive.org) and more recent debates don’t alter the point I’m making here.

The mirror metaphor works perfectly here. What youve shown is how court historians could critique power without directly confronting it - describing an idealized Rome becomes a way to highlight Liu-Song failings without getting your head chopped off. That detail about the thin, lead-heavy coins really drives it home - physical evidence of the financial strain that made those references to full treasuries and honest prices sting. The careful dance between preservation and commentary in these official histories is fascinating, especially when you realize posterity was part of the intended audience too.