Hello, hello,

Happy Friday and I hope you and yours are well.

This week has involved a certain amount of running around but also a bit of decompression with something I had never thought to look for: cosy crime mysteries with a historical twist.

The historical side of things is pretty lite but a recurring character is an archaeologist and the author has done enough research to know that if you want nitty-gritty lab archaeology doing on your samples, at least in the UK, you send it to Bradford University not [insert famously elite institution of choice here]. If that sounds like fun to you, too, check out the work of Kate Ellis (who is also quite prolific, so that should keep me in comfort reading for a bit).

It has also been a good few weeks for ‘finding lost cities’ from the Middle Ages. If that, too, sounds cool to you, find out more here and here.

I have thoughts about lost cities, for another day, though we might start with: if you are doing Lidar (drone flying lasers over a large area to find out what’s under the vegetation), then you didn’t really find whatever you found ‘by accident’, but I get that it makes a good headline and I’m genuinely delighted for all involved!

This week, though, here is a funny story I found some time ago and think more people should know.

Hilarious Histories

Now, laughing about the past is a touchy point for me. I deeply dislike laughing at people in the past (or, indeed, anybody) because they are different.

Isn’t it hilarious they didn’t have indoor plumbing/couldn’t split the atom/died of diseases that are now easily preventable (but somehow not easily prevented on a global scale)?

No, not really.

Isn’t it funny they held strong religious beliefs (because nobody does that now?!)/didn’t know where all the continents were/thought the Earth was flat?

Nope. (And, FWIW, mostly people didn’t think the Earth was flat - it was and remains what we might call a marginal position.)

There is a brand of humour about the past that is both ‘look, they were different!’ and also ‘look how much better we are now!’ that irks me.

That doesn’t mean history is joyless or dry. History can be hilarious, which begs the question, what kind of comedy do I like?

That is a much bigger question than you or I need an essay on, but it definitely includes the situational equivalent of the banana skin: something unexpected catching out the best laid plans. It also includes relating to the petty frustrations and complexities of the everyday. I’m more sitcom than stand-up.

And a few years ago, I was reading an article in the Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society that made me laugh out loud. So here it is, with thanks to the great scholar of East (and, on this occasion, Southeast) Asian numismatics, François Thierry, now retired Curator of Oriental Coins at the Bibliothèque nationale de France.1

Setting the Scene

The title of this very short piece, published in 1995, is 'The Silver Taels of the Douanes et Régies d’Indochine (1943-1945)’, so let’s start with a bit of context.

What is a ‘tael’? Glad you asked…

The word comes into English from Malay, where ‘tahil’ means ‘weight’. English got it from Portuguese (which rendered ‘tahil’ as tael) because of the Portuguese being the first European power to open up frequent and direct trade relations with Southeast Asia from the fifteenth century.

Although the word ‘tael’ has no link to Chinese, the weight that it refers to comes from the traditional system of Chinese weights, and is equivalent to the Chinese ‘liang’. In 1959, the Chinese liang/tael was standardised at 50g. Before this, exact weights varied from region to region, but averaged around 40g.

Historically, the term tael often referred not just to a specific weight, but to a particular coin of that weight. Silver ‘taels’ were issued right across Southeast Asia by various authorities from the Early Modern period (c. 15th century) onwards. Thierry is talking about one such coin.

Okay, so what about the ‘Douanes et Régies d’Indochine’?

Let’s start with a literal translation: ‘The Customs and Government Corporations of Indochina’.

Indochina refers to the area of the modern states of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, which were all parts of the modern French Empire, then the French Union.

Government of the region was complex. Some areas (notably, Cochinchine, in the bottom middle of the map, not in yellow) were governed by a French prefect and bureaucracy. Other regions had varying levels of autonomy under local royal families, but, like other European overseas empires, things like defence and international relations tended to be managed by the colonial power.

The Douanes et Régies d’Indochine (hereafter, DR) was a government office which oversaw many of these matters, especially relating to trade and finance.

Finally, what was going on in French Indochina in 1943-45? As only a brief background for the story that follows, it was a time of upheaval and the weird continuity that often co-exists with historical disruption.

Japan steadily seized control of French Indochina from 1943, holding it until the defeat of Japan in 1945 by the Allied forces of the US, UK and British Empire (as active combatants). Between 1943 and 1945, what are now Vietnam and western Cambodia were given by Japan to its regional ally, Thailand, but in most places the existing bureaucracies carried on functioning.

Of course, in the background to all of this, the Second World War was raging on land and sea.

Not a promising time for numismatic hi-jinks, you might think, but in the midst of chaos, life goes on…

The Problem

In 1943, the DR set up a special board for buying opium from various inland tribal groups.2

Our tale begins when a Monsieur Laroche was appointed head of the opium buying board and decided to create a new currency specifically for that purpose.

Two people were delegated to the job. Head Customs Inspector Pascal Morani would be responsible for sorting out the design and manufacture of the new currency, while Head Customs Inspector René Lafont would sort out the finances.

Initially (and very sensibly) they came up with Plan No. 1: to produce silver ingots, often known as ‘silver bar’ or ‘snake neck’ currency in the region. This was a good idea because these ingots were already widely used, especially by the Hmong (referred to in the article as Meo), one of the largest opium-growing groups. People are generally conservative when it comes to using things as money, so things that look and feel familiar are a safe bet.

But… where to make the ingots? A new mint was established in Hanoï but proved technically incapable of this feat.

Plan No. 2

The next idea was the creation of a new silver token coin, i.e. something that looked more like a coin as we think of coins today - round with designs on both sides, usually combining words and images.

Here, another character enters the stage. M. René Mercier was the newly appointed engraver at the newly established Hanoï mint. (What could possibly go wrong with all of this absence of institutional knowledge, right?)

Mercier came up with some designs and Laroche (the person in charge of the whole opium buying malarkey), chose one with a Chinese character on one side and a Lao inscription on the other and decided they would issue two denominations: a full tael (at 38g) and a half tael (at 19g).

But… somebody had not done their homework. The groups growing the opium, and again, especially the Hmong in the region, were not Chinese speakers, so did not understand or recognise the Chinese character. Apparently, the Lao inscription, which was in their language, was incorrect - never a good look when building trust with trade partners.

By now, things were getting a bit pressured. Opium is a seasonal crop and duff coins on the No. 2 design had been produced in winter 1943/44 especially for the 1944 opium harvest and now, apparently, were no good.

On to Plan No. 3

This time, the decision was to try to get it right. Laroche (head of the operation) and Morani (in charge of production) put together a Special Commission made up of ‘students of ethnic minorities’ (it is not completely clear to me from the original article whether this means people who studied relevant ethnic minorities or students who belonged to relevant ethnic minorities, or both, or a combination of either).

The Special Commission included at least one member of the Hmong, Prince Tougeu Lyfoung.

The commission decided on the design of a stag’s head.

A famous Hanoï jeweller was tasked with engraving an exemplar but here the problem of intersectionality kicked in or, more correctly, lack of intersectionality. The jeweller and the relevant groups trading opium were all ‘Indochinese’ in colonial terms, but did not belong to the same cultural groups or lifestyles. In particular, the jeweller from Hanoï was very much an urbanite.

When asked to engrave a stag, he went to the most obvious place for a city-dweller to find one: the Larousse illustrated dictionary. However good his engraving may have been, when the new coin was shown to the Hmong they were confused. The European ten-tined stag on the coin didn’t look anything like any deer they had ever seen.

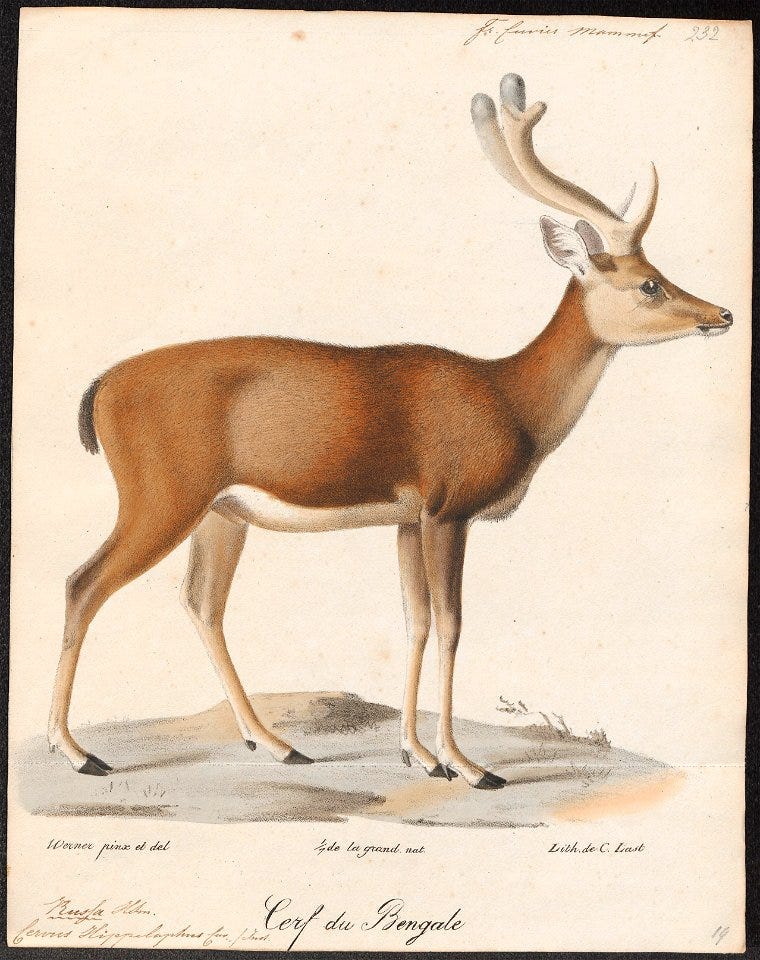

In fairness to the jeweller, he had tried. He also produced a back-up stag that was found locally: an engraved image of Cervus hippelaphus, and this is when I started laughing with a kind of sympathetic Schadenfreude.

Because, the Cervus hippelaphus was local but unfortunately looked an awful lot like another locally-available ruminant ungulate, the Cervus muntiacus or Muntjac deer. And the Muntjac is a symbol of bad luck among the Hmong.3

Take 4! (I’ll just do it myself)

By now, Pascal Morani (in charge of getting the currency actually made) was getting impatient and apparently decided to just do it himself. He drew out the head of a six-tined sambar stag (Cervus aristotelis) and engraved a die.

This is no mean feat. He doesn’t seem to have done much (any?) engraving before and it involves being able to reverse an image and carve it manually into hard metal, so kudos to Morani, who must have been pretty annoyed by now.

Still, there is often a cost to learning on the job and his first attempt didn’t work because he cut the image too deeply into the die so, when the coins where struck, the metal didn’t actually fill up the void and pick up the pattern.

Aside: these silver coins were being die-struck, meaning that a round silver blank is placed between two dies, each carved with an inverse image of the desired design, then, with various levels of technological intervention for accuracy, labour saving, etc., the whole arrangement is hit with a hammer, squashing the blank between the dies and impressing the design into it. If the design is cut too deeply, the blank won’t squash far enough and there will be empty parts in the design.

Plan No. 5

Not to be defeated, Morani had another go. This time, he managed to scratch what should have been clear parts of the design twice with his engraving tool, but by now everybody seems to have run out of patience and it was decided to run with the die anyway.

The taels that were produced this way have a thick border around the design, which was an intentional choice: by pressing dies into blanks that are much bigger than the die area, the outside edges squish outwards and upwards, giving the outer rim a nice chunky feel that it was thought would make the coins even more acceptable. They are also recognisable for those two scratches in the original die.

In the end, the run of these deer taels was pretty short. Minting began in late 1944 and was stopped on 9th March 1945 by the Japanese takeover of Hanoï.

Epilogue

One of the most charming things about Thierry’s article is that, in a privilege we scholars of the deeper past rarely get (most of Thierry’s work is on ancient and medieval coins), he was actually able to speak to several of the dramatis personae.

In particular, he met with and showed examples of the various stages of the coinage to both Morani (the indefatigable amateur engraver and administrator) and to Prince Tougeu (brought into the Special Commission to pick a design for the coins).

They confirmed which designs were which but there was a further complexity: some examples of other kinds of stag-head taels, not engraved by Morani, also carry the two distinctive scratches that he made by accident.

Thierry’s best guess? Since the various iterations of the coins are now quite collectible and the two scratch marks are a distinctive identifying feature, forgers may have started putting them on any stag head taels to make them ‘look the part’.

Learning Curves

Something in this story got me in the place of amused empathy, when something that should have been fairly simple becomes a litany of minor or unforeseen trip hazards.

It also caught my attention for a lot of other reasons, which have kept it in my mind ever since.

One is the importance of silver. This is a long-running research interest and as a result I collect examples of silver being the medium of choice for trading, especially with people on the edges of monetary economies.

The Hmong and other inland groups did not have a currency of their own but it is fascinating to me that none of the existing currencies in the region at the time were felt to be suitable.

Presumably, the currency needed to be intrinsically valuable, since it was being used more as a ‘token’ or a product for trade than money in the fully symbolic sense. However, there were other silver currencies available, including those snake neck ingots that apparently couldn’t be made properly in Hanoï.

Was it too expensive to acquire these through trade just to them trade them again for opium? If so, that indicates that they were circulating above their silver value (which is normal for coined money) and the DR expected this to be true of their new tokens, too.

There is also something revealing in this story about the contingent, even slapdash nature of colonial regimes which so often projected an appearance of omnipotence and efficiency. That appearance, of course, was part of their mechanism of control. Knowledge is power and empires have often been central producers and storers of knowledge.

Possession of bureaucracies of knowledge, from archives and censuses to public proclamations and maps, is a theme in colonial histories because these are all visible declarations that the reigning power can see, can know, and therefore can control.

What were the limits of these assertions of knowledge, though? It is a problem for scholars of all periods and regions.

The Roman Empire, for example, never conducted an empire-wide population census of the sort described in the Christian Nativity story, but evidently the writers of the gospels thought it was reasonable and believable (and likely believed themselves) that a pregnant woman might travel a hundred miles in the dead of winter because an emperor in Rome wanted to count all of his subjects. This is the ambivalent power of the appearance of knowledge.

In the tale of the taels we see the flip side of the coin (sorry, couldn’t resist). The extensive gaps in colonial knowledge are revealed, even in an age of much greater technology:

how to make good ingots

how to write correct Lao

what language key trade partners might respond best to

what sort of deer are and are not found regionally

what sort of deer are omens of bad luck and to whom

apparently, how to find an alternative engraver in a large city

So many things unknown that could have made silver currency for buying opium a much simpler and less frustrating process, but knowledge is difficult. Looking at that list, it is easy to see why one small team of harassed functionaries on the edge of an empire embroiled in a global war might not have had access to it or even known where to ask. They may not even have known that some questions needed to be asked because knowledge is often acquired as a result of error.

It is also often a site of resistance and negotiation and I wonder how much we see that in the shadows of this numismatic story.

Could the Hmong and other inland people really not have risked trading opium for not-quite-right snake neck ingots? Was a ten-tined deer really so distracting that doing business was impossible? How bad was the botched Lao legend on the first attempt at a trade token and exactly how unlucky is a Muntjac?

The numismatist in me suggests that people can and will do business with all sorts of weird and wonderful approximations of a known currency, if it suits them to do so. The case of the taels suggests that it did not suit the Hmong to do so. Knowledge of their own customs and environment, and of their bargaining power with officials in a difficult position from a distant city, created a space for asserting autonomy and perhaps simply for giving colonial authorities a taste of their own, often very arbitrary, medicine.

In the form of a Special Commission the taels also reveal how negotiations over knowledge can be a trigger for finding out more and finding new ways of finding out.

Thierry, François, ‘The Silver Taels of the Douanes et Régies d’Indochine (1943-1945)’, Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society, 143 (1995), p. 16

The government of French Indochina was one of the last in Asia to restrict sale and supply of opium, not doing so until 1947, though public efforts to manage the trade from the 1920s to the 1940s ended up being a much bigger scandal, involving spurious accounts and fudged reporting that ultimately caused a serious financial crisis. For more information, see Kim, Diana S., ‘Disastrous Abundance in French Indochina, 1920s–1940s’, in Empires of Vice, by Diana S. Kim (Princeton University Press, 2020), pp. 153–82, doi:10.23943/princeton/9780691172408.003.0006

I was absolutely delighted to find this article, which opens with ‘Deer classification is a contentious subject…’ Just to make my broader point: knowledge is difficult.

Thanks for sharing this delightful story! Reading through the deer classification article, I find it highly amusing that some controversy is mentioned every few paragraphs. A contentious subject indeed!