The HAL Airport Hoard

(When the present is full of confusion, take refuge in the past. The coins will always be there.)

This week has all been a bit unexpected. I am writing not from Hyderabad, as I had expected, but from Bengaluru (formerly Bangalore). All I will say for now is that at least things fell through very quickly, so I’m stumbling out the other side of one of the weirdest weeks of my life but hope to recover swiftly.

Forgive me if this all sounds very cryptic. I have a lot of things - personal, emotional, practical and governmental - to process! Rest assured, I am well, and safe and have had a week of being reminded that good friends are a matchless blessing.

It has rather left me wondering what to write about this week, though.

Bengaluru? I could give you a potted history but, honestly, I would just be telling you what the internet told me. The city is quite a late development by my early medieval standards. The name is mentioned on a hero stone from the 9th century (stones inscribed with the names and a brief record of the deeds of men who did heroic things, often involving acquiring other people’s cattle) but it really only got going as a fort and urban centre in the 16th century.

My own experiences of Bengaluru? Because it is out of period for me, I didn’t really visit on any of my previous trips to India. My only memories of this city, before this week, are animatronic dinosaurs in the science museum and sitting at the bus station on my way to Mysore reading Rabindranath Tagore. I strongly recommend his work to you, if you don’t know it, but this isn’t a literature blog.

How about Roman coins found near Bengaluru? That seems more like it! Roman coins were what first brought me to India. They were why I first began learning Tamil, which has made me so many friends and continues to connect me to India even during long absences. They are also one of the hubs around which my now quite diverse research interests cluster.

Let me take this opportunity to tell you a little bit more about how I ended up being the historian I am and the coins that started it all.

Roman coins have been documented in South Asia since at least the fifteenth century in European sources. Before that, going back to the early first millennium CE, local inscriptions, especially in the central part of the peninsula record coins (or possibly units of account) called ‘dinara’, a rendering of the Roman term ‘denarius’, which was the name for the most common silver denomination of the early Roman coinage system.

For Europeans who began to visit and then live in South Asia in larger and larger numbers from the 1470s onwards, these coin finds confirmed accounts in Roman texts that were part of the standard school curriculum in Europe. The first-century writer, Pliny, for example, talked about Romans loving Indian luxuries:

‘It is an important subject in view of the fact that in no year does India absorb less than fifty million sesterces of our empire’s wealth, sending back merchandise to be sold with us at 100 times its prime cost.’ Pliny, Natural History, Book 6.101.

The second-century writer, Strabo, wrote about how many ships left for India each year, returning with pearls, silks, spices and incense.

The coins were seen as proof of their accuracy. Since then, centuries of work has gone into trying to understand these coins: how many have been found, where, dating from when? What happened to them when they reached South Asia?

The answers to none of these questions are simple, as one find near Bengaluru (indeed, the only significant find of Roman coins near Bengaluru) demonstrates. It is known as the HAL (Hindustan Air Lines) Airport hoard.

Coin finds are usually divided by numismatists (people who study coins) into two broad categories: hoards and single finds. There have been some attempts to make more complicated categorisations but they haven’t been widely accepted.

A single find is pretty much what it says it is: one single coin, found on its own. A hoard is anything else: two or more coins, found together.

There are definitely grey areas.

If a bunch of coins of different periods are all found at the bend of a river, where it is obvious from other debris that stuff tends to accumulate because of how the water moves, is that a hoard, because they are together, or a group of single finds?

What about a field, where lots of coins are found all over the place? It could indicate a marketplace, where lots of people dropped single coins over a long period of time. Alternatively, it might be that a hoard of coins, perhaps in a bag or pot, ended up being caught by a plough centuries after it was buried, scattering the coins across a wide area.

These edge cases don’t invalidate the categories. Instead, having to ask the question makes us think harder about the evidence.

In the case of the Bengaluru coins, they were pretty clearly a hoard. The coins were found in a clay pot. Unfortunately no pictures were taken of the pot. This wasn’t uncommon until quite recently and not just in India. For a long time, coins tended to be treated differently to other archaeological materials.

Specifically, they have tended to be treated as ‘treasure’, unless they are found during an actual archaeological excavation. (In fact, under both UK and Indian law, ‘treasure’ is a legal as well as a subjective category, which also shapes how things are treated.) As a result, things that treasure was found in were often not considered as important as the treasure itself. There is a parallel case here with the way that things associated with mummies in early Egyptian archaeology were often thrown away because the mummies were the important bit, or medieval layers on ancient sites in Greece and Italy were scraped away because the statues and columns were what people wanted.

Anyway, in this case, the pot that the HAL Airport hoard was found in is described in reports as ‘Roman’, but the pot wasn’t kept, drawn or photographed and we know a lot more about South Asian pottery styles from the first millennium than we did in 1965 when the hoard was found, so we can’t be sure that the pot really was Roman. However, we can be pretty sure that the coins were intentionally buried, together, in a pot. A classic hoard.

Obviously, they were not buried at an airport. Hoards tend to be given the name of the place where they were found and usually that is not the same as whatever the place may have been called when the hoard was buried. Usually, we just don’t know. This is one of those cases. We have a hoard, unearthed while building work was going on to build the airport that now serves Bengaluru. That is all we know, so that is what the hoard is called.

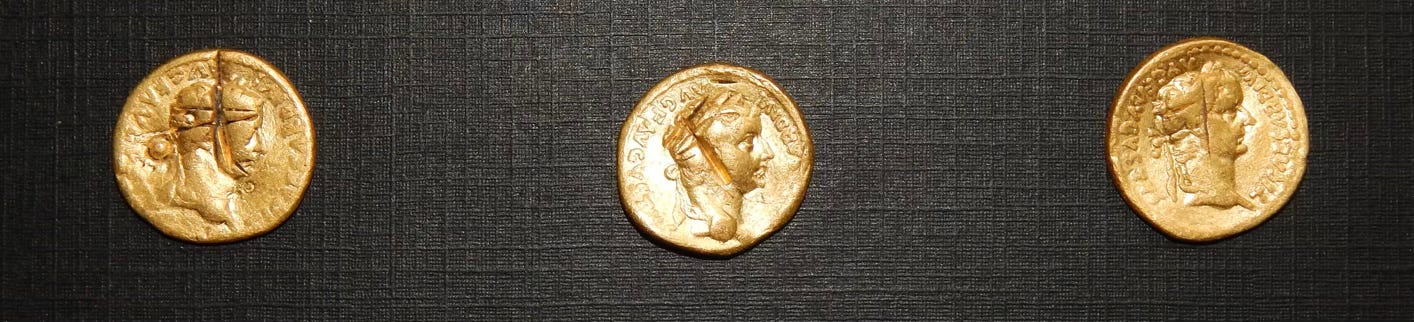

What was in it? The HAL Airport hoard contained 256 silver denarii of the first-century Roman emperors Augustus (reigned 27 BCE-14 CE) and Tiberius (reigned 14-37 CE).1

Coins of these three emperors are particularly common in India, which is probably mainly to do with the fact that they produced a lot of coins. Their reigns also saw a huge expansion of urbanism and the consumer economy in the Roman Empire, giving an incentive to traders to go further afield in search of goods, including from the Indian Ocean.

In fact, Roman silver coins from the first and second centuries CE have been found in thousands, in hoards and as single finds, right across South Asia.

From the second century, though, they began to be replaced by Roman gold coins, indicated on the map above by yellow points (showing hoards and single finds of Roman gold coins dating from the first to the third centuries CE). Changes in the Roman coinage system and perhaps also in local South Asian economies made gold coins preferable in this trade.

Fascinatingly, both gold and silver coins show signs of people interacting with them, not just as money but also as jewellery or objects to be imitated and marked.

It is the modification, imitation, hoarding, hanging on necklaces, possibly even depicting in sculptures, that sucked me into the study of Roman coins in South Asia. In a tiny object, across thousands of years, it is possible to see individual human choices: to decorate or be inspired. It is a glimpse of how foreignness looked to people long ago, whose names we will never know.

The coins of the HAL Airport hoard are not actually precisely the coins that first brought me to India. They are not slashed, pierced, or imitations made locally of Roman coins. They are also a bit early.

For me, the real draw was gold coins which began to be imported to South Asia from the Roman Empire just a few centuries later, mainly from the fourth century, and which are marked on the map above by the olive-green spots.

They looked slightly different and had a different weight to the earlier gold coins, because of economic and ideological transformations in the Roman Empire (including the legalisation and spread of Christianity). They are not found exactly in the area around Bengaluru: they concentrate in the south of the peninsula. But they show the same signs of wear and use and modification and imitation.

Trying to understand these coins, though, has required looking back at the earlier finds, like those from the HAL Airport hoard. It has taken me on many journeys: across India, to Sri Lanka and the USA and Austria, into the study of colonial and post-colonial archaeology, the history of collecting, theories of design and propagation of images and the role of coin in establishing political regimes.

Coins are so small yet the worlds they hint at are so huge. Think about that next time you’re handing over small change :). And more next time on Roman coins from South Asia!

This information is taken from the still-definitive work on Roman coins found in South Asia: Turner, Paula J, Roman Coins from India, 1st edn (Royal Numismatic Society, 1989).

I will never forget one of my first undergraduate classes with you where we learned about the histories that can be unearthed using coins. I have not looked at them the same way since!