What if, every time we imagined somebody doing something in the past that could reasonably have been done by either a man or a woman, we imagined it being done by a woman?

This isn’t an especially new question and I don’t take any radical points for posing it. In fact, it was first posed to me by a friend who was, in turn, summarising a paper by a very senior and brilliant scholar of early medieval Europe, Professor Rosamond McKitterick FSA, FRSA FRHistS (because even though Rosamond is lovely and would never insist, dammit she earned every one of those titles and acronyms and it meant a huge amount to me as a junior scholar seeing senior, kick-ass lady scholars at the top of our field and being recognised for it).

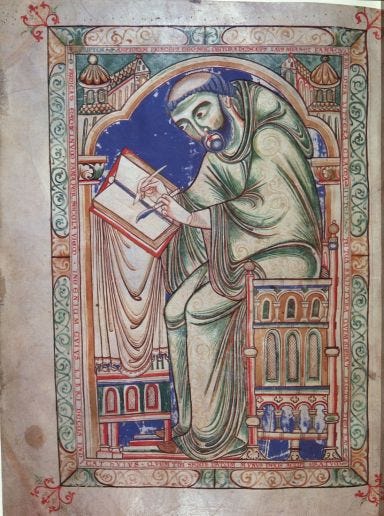

Rosamond asked, what if, every time we have a handwritten document - a manuscript - from the Middle Ages, and we don’t know who copied it out, which by the way is almost all the time, we imagined that the scribe (a person who writes) was a woman? There is, she rightly points out, no reason not to imagine a lady scribe.1

We know full well that there were plenty of educated women in the Middle Ages and that there were women who lived in religious communities that practiced copying manuscripts. We even know of specific communities of women who were actively interested in finding out stuff about things, via one of the standard medieval means of doing that - collecting manuscripts and copying them, often annotating as they went along with extra information, ideas and, yes, sometimes, pictures of willies growing on trees. (Haven’t we all felt that way about what we’re reading, now and again?)

If we know all of this, then what is the problem? Why don’t we imagine lady scribes producing many of the manuscripts that survive from the Middle Ages?

Some of the problem is the role of imagination in doing history. In theory, we all know that imagination plays a big part in understanding the past. It is the glue we use to hold our evidence together and make it into shapes we can understand. When it comes to our specific topics of work and our published conclusions we can theorise quite eloquently about how imagination is helpful and necessary and challenging .

In everyday practice, though, as we think through the everyday worlds that framed the specific things in the centre of our field of view, we don’t always imagine in this very rigorous and theoretical way. We imagine with lots of historical information, but we can also miss when some of the assumptions and habits of our own everyday world slip into the picture.

I think this is what has happened in the case of lady scribes. Because we don’t generally talk about how we imagine the past in our day-to-day historianising, as opposed to the smaller element of presenting that historianising publicly, we absorb what is in the water around us and what was in the water for scholars before us.

And when it comes to lady scribes, I don’t think I’m alone: unless somebody in a historical source is actually specified to be a woman - a mother, a nun, a widow - or does a very small range of jobs that we tend to associate with women (even though they could all be done by men), in ways that tell us a lot more about modern gender stereotypes than the past - midwife, sex worker, dancer - I tend to see men.

I can stop and go back and edit my picture, but mostly, like everybody else, I’m busy, and this person is likely tangential to whatever it is I’m trying to find out, so I don’t. The default sticks. The farmer, the street vendor, the landlord, the weaver, the glass maker, the oil-press worker, the scribe… They all stay as shadowy imagined, male figures.

Now, sure, there were jobs that were not supposed to be done by women in the past, so if we want to imagine a woman doing those jobs, we should have some really good evidence for doing so and should recognise that we are probably looking at quite unusual women, but there were lots and lots and lots of roles in the past for which this is not true and, indeed, for which we have plenty of evidence for women being actively, even equally involved.

So, how to go about imagining women? First of all, I’ve realised, comes actually deciding to bother.

Second, it has helped me to recognise that imagining women is difficult because it requires trying to see past two layers of assumption. Not only am I imagining men by default in the past, but so did people in the past. If a medieval painter (who may have been a woman!), painted a farmer or a street vendor, they would usually be painting their ‘typical’ or ideal farmer or street vendor, not a specific one, and so they too would likely paint a man, because their social stereotypes entailed men in public roles and women in more private spaces. (Idealised images of childcare would usually feature women even if we know that lots of men had loving, active roles in their children’s lives.) They didn’t imagine that way because it was true, but because we all live with conventional images of the world that are really hard to shake.

For these reasons, the third and most important thing I tell myself to do is keep practicing. I have spent decades imagining the textures and smells and sounds of the pasts I study: the feel of cloth against skin, the taste of food, the temperature of the breeze coming off the sea on a beach of golden sand. These things make those worlds alive to me, so that I can make them real for other people. But I have mostly imagined that cloth against male skin, the golden sand between the toes of a man in sandals, and the food in the mouth of a man. Weird, isn’t it, since I am a woman? But that’s habit for you!

At the moment I’m writing a book about a text which survives in only a handful of manuscript copies: three, to be exact. We can be pretty certain that the author of the text, who lived in the first century CE, was a man. This week, however, I found myself thinking about Rosamond McKitterick’s salutary call to action because somebody in ninth-century Constantinople sat and copied this text, by hand (a very even, well-trained hand) onto good quality parchment, using ink that probably looked black then but now appears a rich, russet red. It is the only reason we are able to read those first-century words.

I see the scribe, probably hunching slightly, even though they know it will make their back hurt, because it is hard to write for hours and hours without rounding slightly at the shoulders. (Ask me how I know. Yoga helps but that wasn’t really an option they had!) They are short-sighted, I think, not for any reason other than that I am, so it is easy to imagine, and lots of people who have taken up work involving close-up detail have been and because short-sightedness can be brought on by reading in poor light from a young age (as our book-loving copyist might have done) and because perhaps being shortsighted may have made it easier for this scribe to go into a monastic life than any other kind of work. At around the same time as my scribe was working, another scribe (this one definitely a man), Florentius of Valeranica, wrote in a manuscript copy he had just completed of the physical costs of this line of work:

A man who knows not how to write may think this no great feat. But only try to do it yourself and you shall learn how arduous is the writer’s task. It dims your eyes, makes your back ache and knits your chest and belly together—it is a terrible ordeal for the whole body. So, gentle reader, turn these pages carefully and keep your finger far from the text. For just as hail plays havoc with the fruits of spring, so a careless reader is a bane to books and writing.

You can find out more about scribes and this quote here.

I am pretty sure my scribe, like Floretnrius, is in a monastery. Monasteries were not the only places where manuscripts were copied in ninth-century Constantinople, but on balance of probabilities, it is a good bet.

An oil lamp flickers if the scribe breathes towards it or a strong wind blows under the door, even with a curtain behind it to keep out the chill. Constantinople, modern Istanbul, is built on seven steep hills and many places in the city catch a breeze coming in off the Bosphorus, warm in summer and bitter cold in winter. Images show us curtains used for warmth, privacy and decoration.

Most of the time, though, my scribe’s lamp burns steady. It is shaped like a teardrop and a cloth wick glows yellow-orange in a pool of fresh olive oil. Lamps like this are found all around the Eastern Mediterranean from the ninth and tenth centuries (and many centuries before and after) and documents record gifts of olive oil to monasteries to keep lamps alight.

The scribe looks up in my imagination, and a face flickers, like the flame of the lamp in a breeze. First a man, middle aged, with a pointed, well-cared for, greying beard and a bald head that shines a little where the light catches it. He might have a tonsure to show he is a monk but he might just be balding. His robes are simple, dark and warm.

Then the face becomes a woman, also middle-aged. In many ways, the woman’s face is not that different. No beard, and a head covering, probably a simple woollen veil over her hair, but I begin to see her, as I see him, as a person, unique and particular, even though I know I am imagining that individuality out of so many generalisations: from images of holy women made in the medieval Roman Empire, from the archaeology of buildings and clothing, from the writings which reveal the order and rhythm of their monastic lives and from real faces I have seen that make the shadows flesh.

Perhaps the fact that the process and the outcome are so similar whether I imagine a man or a woman was always Rosamond’s point: it does no damage to what we know about the past to imagine that this scribe, or any scribe, was a woman rather than a man. It does not require any great mental gymnastics, or the falsification of any data. It does not involve speculating beyond the limits of our knowledge or doing violence to the laws of probability. We simply do not know how many nuns there were, compared with monks, in Constantinople, and of those, how many were scribes, and in any case, we are not talking about all of them. We are talking about one - one scribe who held one quill and wrote one manuscript and who might have been a woman as easily as a man. In some ways, it makes no difference.

In other ways, this act of imagination remains as important, and as radical, as it was when Rosamond suggested it. It demands effort, not just when I put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) and publish something, taking care to add the now routine caveat - he, or maybe she. The point is to make the effort every time we think about the past. That effort is not to overcome the possibilities of the past, which didn’t have a problem with women doing all kinds of things. It is to overcome the limits of imagination in the present.

Imagining my lady scribe, I am not insisting that she was a woman. We will never know. I am simply saying that we shouldn’t rule it out, or even find it very unlikely. In my own life that has always seemed a good everyday yardstick for how I hope to be treated and how I try to treat others: I don’t want to be given more or different or better opportunities than anybody else, but I would like not to be ruled out because of who or what I am. It is surely the least I owe the people whose lives I study.

Rosamond McKitterick, ‘Women and Literacy in the Middle Ages’, in Books, Scribes and Learning in the Frankish Kingdoms, 6th to 9th Centuries, by Rosamond McKitterick, Variorum Collected Studies, 452 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1994), p. XIII: 1-43 (pp. 22-25)