Tinker, tailor, soldier, cheesemaker...

Or, if you can't trust a cheesemonger, who can you trust?

Hello,

Greetings and good wishes: I hope your week has been good!

This week, I’m skipping over coffee and enjoying my history with the cheese course. Maybe set yourself up a cracker or two and nibble while you read…

The Grate Cheese Robbery1

Last week I wrote about a money scam that wasn’t quite counterfeiting (specifically, not quite, as defined by the Indian criminal code!) but was still doing nefarious things with the currency of trust.

This week, another news story was so on the nose for those themes that I couldn’t resist talking about it. It also speaks to a subject that I now watch out for with special interest, thanks to a friend and regular reader here: cheesemaking!

So, what’s the story?

Or, more accurately, the story so far…

My eye was first caught by the headline last Friday, 25th October, possibly even exactly when you were reading me, talking to you, about dodgy money and trust networks in western India…

So many questions!

Where do you put 22 tonnes of stolen cheddar?

Where do you even find 22 tonnes of high-quality cheddar in the first place?

How much is 22 tonnes of top-quality cheddar worth anyway?

Why ‘fraudsters’, not robbers or thieves or just ‘criminals’?

Some answers were immediately forthcoming from the article that first caught my attention:

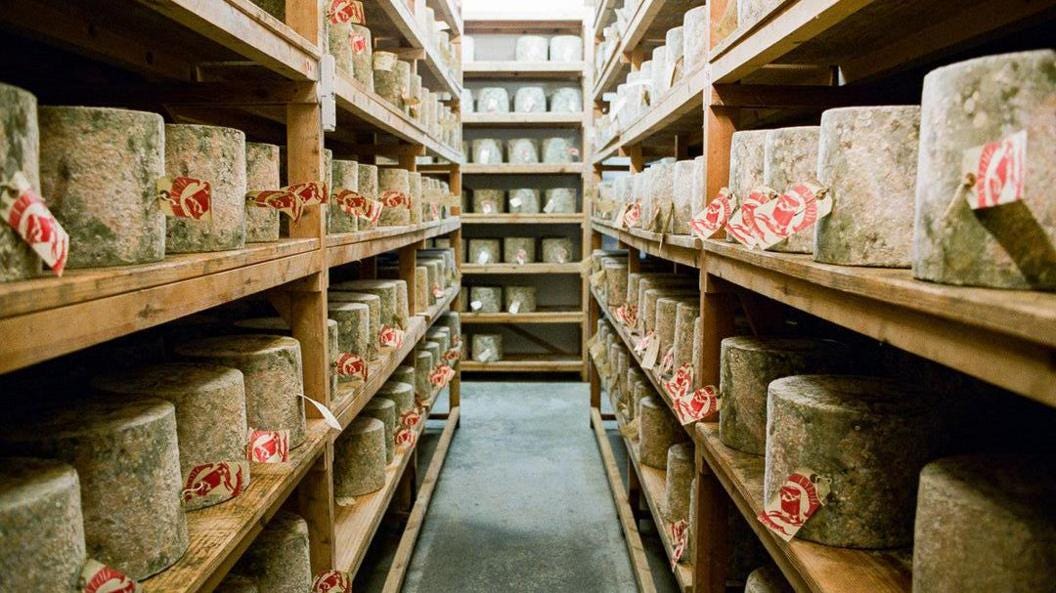

You can find 22 tonnes of high-quality cheddar at Neal’s Yard Dairy in Southwark, London. I had a friend who once lived in Southwark, and it is a trendy bit of London full of Victorian warehouses and industrial premises, now turned into galleries, upmarket housing and shops that use ‘artisanal’ as a core branding, so this all tracked and helped me to picture the scene of the crime. I also have a(nother) cheese-obsessed friend from whom I’d heard the name Neal’s Yard, so, leaning on my own networks of trust, I had immediate confidence that these might, indeed, be purveyors of most excellent aged dairy products.

The cheeses stolen were three particularly valuable artisan cheddars: Hafod Welsh, Westcombe and Pitchfork. All of them retail, via Neal’s Yard, for around £30 per kilogram, so the answer to ‘How much is 22 tonnes of top-quality cheddar worth anyway?’ is, apparently, roughly £300,000 (GBP).

Other questions remained open but hinted at. In that first story, for example, the makers of one of the stolen cheeses was quoted as saying:

"The artisan cheese world is a place where trust is deeply embedded in all transactions.

"It’s a world where one’s word is one’s bond. It might have caused the company a setback, but the degree of trust that exists within our small industry as a whole is due in no small part to the ethos of Neal’s Yard Dairy’s founders."

And I found this very moving and commendable: people pulling together, recognising their inter-dependencies and showing support in times of hardship rather than, e.g. complaining that Neal’s Yard let their cheese get nicked, is the sort of thing that reassures me about human beings in general. Earlier in the same story, Neal’s Yard was also quoted stating that they would pay the suppliers and absorb the cost of the theft themselves, so there was a lot of love and mutual support going on, but it did not answer my question of ‘why fraudsters’?

Trust was obviously at issue in some way, but the first reports about the theft did not explain exactly how. If I were examining this single article a thousand years later, with no other information available, I would feel fairly confident in saying that nobody used threats or violence: there was no ram-raid in the middle of the night and the screech of wheels as the cheeses rolled away.

The Plot Thickens

A few days later, on 28th October, another story filled in some of the gaps: a buyer, pretending to represent a major French supermarket chain, came to Neal’s Yard Dairy, and arranged a large purchase. The cheeses were moved to a warehouse elsewhere in London, at the buyer’s request, but then no payment was made. When Neal’s Yard Dairy made further inquiries, the warehouse had been emptied and the buyer had vanished.

Up to this point, I had been interested because,

cheese theft seems inherently interesting to me

it gets the word ‘truckles’ into popular news media

I like stories (see above) about people being supportive of one another (this new story contained updates that the cheese community has rallied around Neal’s Yard Dairy:

On Monday, the firm thanked those who had "rallied" to support the business since the news of the theft and said it had received "an overwhelming number of calls, messages, and visits".

It said: "We are truly touched that so many people in the artisan cheese community and beyond are standing with us. It's a reminder of why we love the work we do."

Now, though, I was interested because I finally understood why the crime was being billed as cheese fraud: the critical element was trust, within a community in which a promise to pay is good enough for a major wholesaler to move 22 tonnes of top-quality product across London.

As with the angadia networks from last week’s look into trust and money, this is really a story about the decisions we (as individuals and groups) make about where and how much in any given process we trust and when and how much we verify.

In this case, the final stage of the fraud looks almost ridiculous easy: walk into Neal’s Yard Dairy, ask for 22 tonnes of cheddar to be delivered to a random warehouse somewhere else, based on an IOU, then sneak it into some lorries and disappear into the night.

It only looks that way, though, because the points of verification come before this point. Now, I have more questions that have not yet been answered.

How long do you have to set up a front to pass as the agent of a major French supermarket in an industry that, according to everyone being interviewed about this crime, is extremely well connected?

What kinds of specialist knowledge do you have to have complete command of to ‘pass’ around other people who really do spend their lives making and selling cheese (rather than stealing it and then, presumably, moving on to other products, because building and burning trust like this is not something you can easily repeat in the same environment)?

Whom do you have to know and, on the flip side, whom do you have to avoid, to appear ‘transparent’?

Yesterday, 31st October, a new update emerged which adds only a little detail but it begins to paint the outlines of a picture: a 63-year-old man has been arrested in connection with the crime. I find myself wondering what role age played in this fraud, and specifically, deeply rooted cultural associations of age with wisdom, gravitas and respect in British culture.

It is too soon to say, but when the heart of a fraud is trying to pass one thing off as another (a forged coin for a real one, a fake banknote for a genuine one, a nefarious stranger for a legitimate cheese dealer…), it often relies on a combination of technicalities (weight, appearance, specialist vocabulary, for example) and broader patterns in human behaviour (familiar presentation or wrapping, or a reassuring personal appearance).

There has also been speculation that the cheeses may be intended for markets in Russia, or Saudia Arabia and neighbouring states, on the basis that these places have strong luxury markets but are not closely connected to the wider networks of artisan cheesemongery. Trying to sell these cheeses in the US, Australia or Europe, it is suggested, would not work, because people would ask too many questions.

And that, too, is interesting because, wherever these cheeses are sold, their value will depend on trust, on the part of the buyer, that they are what they say they are. There is little point fraudulently obtaining truckles of cheddar that retail for £30 per kilo because of transparency and trust (in the production processes and original ingredients) then having to sell it for £10 per kilo because there is nothing reliably to distinguish it from any other cheddar.

For comparison, forged coinage or banknotes only need one point of trust to work - when they are first put into circulation. That is what makes them so dangerous and what makes laws about not forging money so strident: once the forger has achieved their aim (of buying goods or services valued in real money for less than that value by using forgeries), it doesn’t matter to them if the next transaction using those forgeries collapses, taking a part of the whole delicate web of trust that is ‘money’ with it.

For a cheese fraudster, there needs to be the appearance of trust on one side of the transaction (the theft part) and at least some reality of trust on the other side (the sale part). The whole process has an almost osmotic quality: the fraudster operates as a semi-permeable membrane between two different environments of trust, exploiting the unequal levels and distribution of confidence among different groups.

Trust and Cheese

At the sale end of the process, though, it is perhaps inevitable that some trust is needed. Money (in the form of coins and banknotes) are designed to be ‘impersonal’, even if they can be used for personal reasons. Theologians and philosophers, from antiquity onwards and right across the money-using world, have urged us to recognise our separateness from money.

Some religious traditions encourage a view that focusing on money is immoral. Others see wealth as a sign of divine blessing. In both cases, though, money is a proxy for other things: for thinking too much about material comfort rather than spiritual merit, or for doing virtuous things and so receiving the rewards of comfort, influence and security that money brings.

Cheese, though? Cheese isn’t a proxy. It is fundamental.

What we eat and drink literally builds who we are.

As a result, somebody passing off forged money may be existential for state authorities - they rightly fear the chaos that comes from trust in a currency collapsing - but at an individual level, it is often seen as an impersonal kind of crime. But lying to somebody about what they are eating or drinking? That seems to feel to people like a completely different issue.2

It is clear from medieval evidence that this has been true for a long time. Take, for example, the Princeton Geniza Project - an online database of tens of thousands (and growing) of bits of writing thrown away in medieval Egypt, mainly by members of the widespread Jewish networks of the time.

These writings are rare from a medieval context because they are numerous, often very ordinary (rather than the thoughts of Great Men or accounts of Big Battles), and mainly related to the business of a minority, non-ruling community, rather than the local political elite.

Plug ‘cheese’ into the project database and, out of just over 37,000 entries, there are 84 references to cheese. That may not sound like a lot, but I was actually surprised. I haven’t counted the number of times ‘cheese’ is mentioned in, say, the surviving corpus of ancient Roman or ancient Greek sources, or the ancient Tamil poems I wrote about here, here, here and here, but it would surprise me if it were a lot. Cheese is exactly the sort of thing that we can know (from images, archaeology, occasional descriptions of feasts or travel) was everywhere, but which can be almost invisible in the kinds of sources that a lot of traditional history is based on.

The Geniza sources provide a rare window into that ubiquitous invisibility. And what they reveal is something straight out of the current Neal’s Yard heist. Take, for example, T-S NS 320.55 + CUL Or.2116.10, a legal document from 1156. It describes the import of 8 moulds of cheese to Alexandria in Egypt from the island of Crete:

When Zeraḥ and Amaṣya originally imported the cheese, they brought with them letters/documents bearing the signatures of the elders of Crete, which were recognized as valid in Alexandria. Those documents from Crete described the entire cheese-making process, from the milking stage onward, and proved that there was no blemish disqualifying the cheese. When the authorities in Alexandria saw this, they allowed the cheese to be sold. (Summary by the editors)

Another document, T-S 8J6.13, also from Alexandria, around a century later (dated to 1260-69), refers to an import of 97 moulds of cheese from Sicily. The cheeses, according to this document, have the correct seal on them and reliable witnesses also testify to them being kosher.

Yet another, T-S 10J24.3 + CUL Or.1080 J174, even refers to a fraudulent cheesemonger. The letter has no date but is addressed to a man known to have died in 1502. The exact nature of the fraud isn’t clear but it involved selling non-kosher cheese as kosher (indicating that kosher cheese commanded a higher price in the market, presumably because of its strict processing requirements).

The exact processes and logic behind kosher cheese and artisan cheddar are not the same but a lot of the trust, transparency and preoccupation with what goes into making food is. The first Geniza document I cited, for example, the purity of the cheese from Crete was established, in part, by disclosing every step in its production to ensure that each one introduced no impurity.

Compare that with Tom Calver from Westcombe Dairy, reflecting this week on the theft of some of his cheeses:

"The process of making that cheese started almost three years ago, when we planted seeds for the animals’ feed.

"The amount of work that’s gone into nurturing the cows, emphasising best farming practice, and transforming the milk one batch at a time to produce the best possible cheese is beyond estimation.

"And for that to be stolen… it’s absolutely terrible."

It shouldn’t be surprising that trust and food go together: it is about safety and, very often, identity. As a result, foods that require specialist skills to make, that are not practical to make at home or that are critical to particular ritual or dietary settings will also provide opportunities for fraud.

Just as issuing genuine coins means constantly battling with forged coins, offering ‘better’ food (whether artisan, kosher or any other category of a ‘better’ for a particular consumer and their requirements) means constantly resisting efforts to trade on that quality dishonestly.

Conversely, though, even if efforts to control dishonest practice are often most visible to us (complaining loudly and eating quietly is not a new thing!), and even if political theorists and philosophers sometimes like to speculate that we are nothing more than bundles of destructive self-interest, barely held in check by laws and force, the ubiquitous invisibles of the historical record tell a different story.

People did make kosher cheese in the Middle Ages and ship it all over the Mediterranean (and, indeed, over to India).3 Artisan cheesemakers in Wales do keep track of which cows in which fields eating which grass end up becoming which truckle of crumbly cheddar. And when fraudsters in 13th-century Alexandria or 21st-century London strike, trust is both the problem and the solution.

It is too soon to say what will happen in the case of the Neal’s Yard robbery but networks of trust may already have shrunk the possible market for the stolen goods. There is not enough data to say exactly what happened in the case of the cheating cheesemonger of Alexandria, but we know he was caught, presumably in part because of not being able to provide the kinds of testimony ‘of reliable witnesses’ that his goods were good.

It is still an eye-catching headline but, like a lot of what stands out in the historical record, it can also be a glimpse into a much bigger story that rarely attracts the same kind of attention:

People make good stuff and don’t defraud each other

Have a great weekend and, if you like cheese, check out Neal’s Yard Dairy online for purchases or just some really interesting institutional history!

Rebecca

No, I didn’t make that up. If I pun, it is unintentional about 90% of the time. I first spotted it reading an article in Restaurant Online from 31st October, but it seems to be circulating widely.

I’m hedging here, with ‘seems to most people’, because, like the distinctions often made between money and other kinds of exchange mechanisms, I think the difference is overstated. Any discussion of financial fraud by its victims, for example, invariably focusses not on the impersonal and numerical (I had £20,000 and now I don’t) but on the emotional and the personal (I can’t believe [this person I trusted, or perhaps, anybody at all] would do this/I had a deposit for my first home and now I don’t).

On this, check out Lambourn, Elizabeth, Abraham’s Luggage: A Social Life of Things in the Medieval Indian Ocean World (University Printing House : Cambridge University Press, 2018).

What a great article, and thank you for writing this - as someone involved with cheese (mostly eating it) for many years, this story was heartbreaking. Let's hope the network of trust really does work both ways, and ultimately against these criminals. I went into Neal's Yard this week to see what I could do by way of support and they told me the best thing is to buy English artisanal cheese. I really don't need that kind of invitation - I left with three different types.