Unexpected romance

A Parthian tale

Hello and welcome (back)!

Grab yourself a cup of coffee (or don’t - that part’s really up to you), and settle in for an unexpected tale from a long time ago in a galaxy very, very nearby. This one, actually. But this story is from one of the parts of it that doesn’t get all that much attention. You see, recently, I found myself reading an article about an ancient love story…

Unfamiliar places, unknown sources

People often say that the problem with medieval history, and a lot of ancient history, except maybe Greece and the Roman Empire, is that there aren’t enough sources. This is a bit like saying a piece of string isn’t long enough: for what?

There aren’t as many sources as we would like to be able to reconstruct every part of life down to the last detail. But that is always the case. A million and one things happened just yesterday that a historian might want to know about, but won’t ever be able to because they weren’t recorded. That’s just life.

It is also true that there aren’t as many sources for medieval and ancient history as we take for granted for a lot of modern history. We don’t have the amount or the kinds of records before, let’s say, c. 1800, that we have for some things and some places after c. 1800.

Ancient and medieval cultures often simply didn’t keep records of things like births, marriages and deaths. If some of them did, the chances of those records surviving 2000 years of fire, famine and flood are much smaller than surviving 200 years.

It is not clear that even an empire as huge, complex and, in some ways, modern-looking, as the Roman Empire kept anything like records of GDP.

So, yes, there is a lot ‘missing’, if by missing we mean, ‘but we wanted it!’

If by, ‘this string isn’t long enough’, however, you mean ‘it’s too easy to get from one end of it to the other’, then we have plenty of sources. There is always more to read, more to find, more to explore. There are now definitely more sources for much of the ancient and medieval world than any one scholar could read in a lifetime.

Still, as a historian, you do get a feel for the ‘greatest hits’.

Even if you haven’t read it, as a medievalist, you’ve probably heard of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,1 or the Book of Ceremonies or the Shahnameh. A lot of this is because of how history is taught: each generation learns about something and so teaches it to the next generation because, even if it might be good for people to know about other things, it seems like a bad idea for them not to know about this.

This is what is usually meant by a ‘canon’: things that a community feels everybody should know about and so prioritises teaching. Often, it doesn’t mean that other things can’t be taught or are intentionally excluded. It just means that there might not be much space left for them once everything in the canon has been covered.

So, a lot of the ‘greatest hits’ of medieval or ancient history are ‘greatest hits’ because they come up at university or school. Even if there wasn’t a course or a class on it, something might mentioned by tutors or in books and articles that you read about other things.

Then there are the celebrities: things that get famous in the field for some reason, such as being discovered in a cave, or whatever.

And then, every so often, I come across something that, as I read it, I feel should have been on one of those lists, surely!? Because it is great: human, engaging, insightful. Fun.

I’m always delighted when I find one of these: a little reminder of how much more there is to discover. So, as I will likely be on a train to Venice as you read this, I wanted to share one of those moments with you: some unexpected romance for the last Friday in January, discovered by me (known to people who specialise differently for a long time) about two weeks ago.

The article I didn’t expect

The author of this particular piece is somebody I know by email and who also periodically shares with me his recent publications, which is always lovely! This was one of them:

Gregoratti, Leonardo, ‘“Parthian” Women in Vīs and Rāmīn’, in IVITRA Research in Linguistics and Literature, ed. by María Paz López Martínez, Carlos Sánchez-Moreno Ellart, and Ana Belén Zaera García (John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2023), xl, 396–406, doi:10.1075/ivitra.40.25gre

The Parthians

Starting from that first word in the title: who were the Parthians?

Good question!

The Parthians get a bit of a raw deal in ancient history. They definitely have their champions, like Leonardo Gregoratti himself, but if there was ever a comparison to be made between how much gets written about the Roman Empire and how much gets written about [anywhere] else, the Parthians would be a good example to pick!

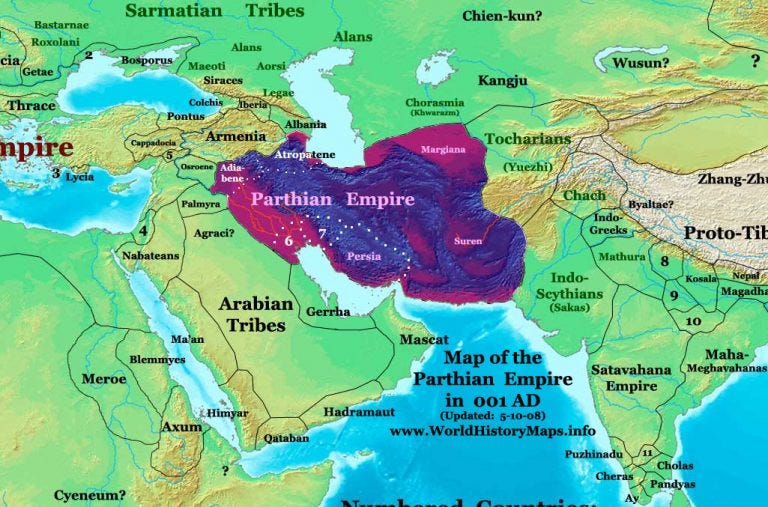

Also known as the Arsacids/Arsakids (or the Arsacid/Arsakid Empire) for the name of their ruling dynasty, the Parthian Empire covered an area comparably vast to the Roman Empire, stretching from the modern Arabian/Persian Gulf to the edge of the Himalaya. They were militarily powerful, regularly matching the Romans in battle. And yet, they can often appear as a bit of a footnote in histories of the ancient world.

There are a few overlapping reasons for this, some of which are about ancient history and some of which are about more recent history. (They are similar to the reasons why the Sasanians also receive less attention than the Romans, which is something I’ve written about here and here.)

In terms of ancient reasons, if the Romans were obsessive about projecting themselves through literature, statues, buildings, forced lifestyle acculturation in their provinces, etc., then the Parthians were a bit more… normal.

That is not, of course, how this tends to be presented in a modern world where the Romans have become the ‘standard’ ancient empire.

Compared to the Romans, you will often hear things like, the Parthians left fewer sources, made less of an impact on their territories, didn’t build as many monumental structures, etc. The emphasis shifts to things the Parthians didn’t do, rather than recognising that how much the Romans did do those things was weird (and was considered weird at the time!).

However, even given the Parthians’ slightly less frantic self-memorialisation, less of what they did produce survives than does for the Roman Empire. And some of this is chicken and egg: because the Romans memorialised themselves so thoroughly they became the medieval model of what a great empire should be, so their stuff was even more carefully preserved, studied and imitated. Because the Parthians did not do this, it did not, etc.

That isn’t the whole story, though. Unlike the Romans, the Parthians were taken over in the third century by a new dynasty, the Sasanians, who were more interested (still not as interested as the Romans, but then, literally nobody ever has been!) in memorialising themselves and who had no interest in preserving the memory of the dynasty they had defeated, even if in practice, they carried on a lot of the same policies and systems.

Plus, this whole region, what is now roughly Iran and Iraq but with some wide margins around it (these were very big empires!), was then taken over in the seventh century, from the Sasanians, by the first Muslim empire.

This change in power mattered because, whereas in medieval Europe the Romans were looked up to as the greatest example of what it meant to be an empire, the medieval Muslim world’s historical narrative was more about how the coming of the new religion had wiped away older powers. This wasn’t a complete contrast, but broadly, the pre-Muslim past received less attention in West Asia than the pre-Christian, Roman, past did in Europe.

Anyway, for all of these reasons, there probably was a lot more Parthian stuff than we now have, even as a proportion of how much less Parthian stuff there ever was than Roman stuff, but they often don’t get the credit they should as one of the major powers in the world in around the first and second centuries CE.

But some tantalising clues remain. This is one of them…

The story

After all of that, can you get on and tell the story already? I hear you cry. Well, here goes:

Once upon a time, there was a queen called Šahru. We are told that she was not young but charming. She ruled a kingdom called Māh. (Scholars think this is a place called Media, but honestly, you don’t need to care unless you want to!)

One day, the Great King, Mo’bad Manikān, approached Šahru with an offer of marriage, but she refused him. A bold move, you might say! Under the Parthians, smaller kingdoms were very independent, but the Great King was still the Great King. (And, for the purposes of the story, his capital city and kingdom is Marv. Marv will come up in the story, but, in case you care, this is probably Merv, now a major archaeological site in Turkmenistan.)

Still, Šahru does refuse him, but with a promise to sweeten rejection: if Šahru ever has a daughter, then her daughter will become Mo’bad’s wife.

In due course, Šahru does have a daughter but, by the time her daughter, Vīs is old enough to get married, Šahru has forgotten all about this old promise to Mo’bad. (As an aside, it has always surprised me in stories from all over Eurasia, from antiquity to early modernity, how often people forget about promising their firstborns to people. It was clearly expected to be a big deal. I guess it goes into the same box as modern movies in which, for plot purposes, half the characters mysteriously forget that almost everybody in the world now has a smartphone and a quick call or web search could fix the whole dramatic crisis in about 10 minutes. Anyway, ancient poets had the same challenges as scriptwriters today and sometimes their solutions were equally improbable.)

Šahru therefore marries Vīs to her son (Vīs’s brother), Vīru. I’ll come back to this later, but yes, you read that right, and no, it isn’t a huge deal. What matters for now is that Vīs gets married to somebody who is not Mo’bad, and Mo’bad is annoyed.

He is so annoyed that he starts a war with Māh, wins and then still, apparently, needs to bribe Šahru to marry Vīs to him, because just winning the war wasn’t enough.

Whether we’re right about where the real places in this story were, it is clear that this action is taking place between two quite distant places and Mo’bad can’t be hanging around arranging his own marriage. He has his own business to attend to, so he sends his brother, Rāmīn to go and collect Vīs and bring her to him.

If this were a movie, what would now unfold is the ‘meet cute followed by travel’ montage, in which Vīs and Rāmīn, thrown together on their long journey, slowly, inevitably, adorably fall in love. I’m sure you can picture the scene. He helps her to sort out the cushions in her palanquin. She befriends his horse one lunchtime and he is captivated by how gentle she is with animals. Their fingertips brush as they both reach for the last dried date… They both know they shouldn’t… (I’m making up these details, by the way, so feel free to invent your own montage and add suitable music.)

It’s Rāmīn who falls first. By the time they get to Marv, he’s head-over-heels.

Vīs is still on the fence about Rāmīn, but she’s absolutely sure that she does not want to marry Mo’bad. Apparently she is not into older men and she asks her nurse/chief lady’s maid for advice. Luckily, this elderly lady knows some magic! Cue a quick impotence talisman, directed at poor old Mo’bad. Even worse, the talisman then gets lost in a flood, meaning that the curse can never be lifted and Vīs is safe from Mo’bad’s unwelcome advances forever. Well, phew. What a relief… for Vīs. But then, love stories often entail a bit of collateral damage.

Anyway, after a while, Vīs decides she is into Rāmīn, they make love, and then run away back to Māh.

Deep into Agony Aunt territory now, Mo’bad chases Vīs and Rāmīn to Māh but Šahru (who is still, it would seem, very charming!) persuades him not to start another war. And she talks Vīs into going back to Mo’bad. Vīs and Rāmīn can’t keep their hands off one another, though, and keep almost getting caught in a series of improbable and pretty graphic moments of indiscretion, until Mo’bad, who may be many things, but is not completely stupid, loses patience and threatens his brother, Rāmīn, at a party.

Rāmīn asks to be sent away to help cool things down and requests a posting to Māh. Mo’bad agrees and Rāmīn pretty quickly meets and marries a new woman, called Gol (not that you need to care - she doesn’t really feature much).

Reaching the high drama of the story, Vīs is furious at her illicit brother-in-law lover cheating on her (!), but Rāmīn pretty quickly realises the error of his ways, abandons Gol and rushes through a snowstorm to get back together with Vīs. (Because nothing says ‘true love’ like risking your life!)

Vīs tries to hold out but in the end can’t help her own feelings and gets back together with Rāmīn. Then they plot an insurrection against Mo’bad with the help of Vīs’s witchy nurse.

Together they hatch a cunning plan: dressed as women, Rāmīn and his gang of merry men attack Marv, take the city and, by way of a secondary adventure, rob Mo’bad and Rāmīn’s other brother, Zard (who, like Vīru, Vīs’s brother/husband, and Gol, Rāmīn’s wife, doesn’t really feature again). The daring young lovers are now rich and in possession of a major city, but… Mo’bad remains free!

It looks an awful lot like the beginnings of a civil war in the Kingdom of Marv, as various lords pledge loyalty to Rāmīn and others side with Mo’bad who (not unreasonably, you might think) is putting together an army to take back his throne.

But then…

…Mo’bad is accidentally killed during a boar hunt!

Oops.

Terribly sad.

The End.

Epilogue: Rāmīn and Vīs get married, live happily ever after for 81 years, have two children, reign justly and well and then, when Vīs dies, Rāmīn grieves beside her tomb for two years before dying himself.

So, there you have it: the romantic erotic comedy adventure epic of Vīs and Rāmīn!

A note on (Parthian) dating

Last week I talked about the ways we might fix a date for when something happened, or was made or written. And this story is a case in point: something very hard to date.

The version we actually have was written by a poet called Fakhraddin Gorgani, who lived in the 11th century (so, about a thousand years after the action in the poem is supposed to have taken place, though it was clearly always intended as a fictional story). You can get hold of the poem here:

Gorgani, Fakhraddin (2009). Vis and Ramin. Translated by D. Davis. Penguin Classics.

There was a real fashion in 11th-century Persian-speaking circles, though, to commission poets to write big, stylish epic re-writes of ‘traditional’ stories, i.e. stories that had probably been preserved as a combination of older writings and oral tradition for centuries.

The most famous of these is probably the Shahnameh by the poet Ferdowsi (also available as a Penguin Classic and just an incredible read!).

These poems are a fantastic insight into 11th-century Persian literary culture but because they also preserve these older traditions, historians are often interested in what parts might be this earlier layer and exactly how early they are.

Why do we think this story is Parthian, then?

The answer, in terms of last week’s guide, is ‘stylistic/contextual’. Specifically, the thing scholars have decided is the right ‘style’ for the Parthian period, rather than earlier or later, is the political culture that the poem describes and takes for granted.

The argument goes: this story would only have made sense to its original audience in a context in which there was a single Great King, but where a smaller kingdom like Māh could still be pretty much independent (remember, Šahru refuses to marry Mo’bad, goes to war with him once, almost goes to war with him again, etc., which would not be possible under a more centralised empire). And the best fit for that is the Parthian period. There are also some clues that the Parthians enjoyed the sort of refined (but still pretty bawdy) adventure epic that Vīs and Rāmīn undoubtedly is.

It’s not an incredibly strong argument. It is possible that the whole story dates from slightly earlier or later. It is certain that lots of the incidental details in Gorgani’s re-telling are actually 11th-century. But the core of the narrative, with the best information we have now, is Parthian.

And there you have it… some stylistic, contextual textual dating in action.

Messages from the past

So, what can we learn from this tantalising love story from a very different time?

First of all, it is worth saying, I am here summarising a summary. I’ve now got my Penguin Classics copy but I haven’t read it yet.

Still, what I found wonderful about the story of Vīs and Rāmīn was how it brings together two of my favourite things about history: how different the past is and how familiar.

People, it seems, have always liked adventure stories. The same motifs crop up over and over again, probably because they put us in the same sorts of situations - away from the familiar, facing impossible conflicts between what we want and what our society demands. We humans love stories about travel, forbidden love and people struggling against enormous odds.

Presumably, people nearly getting caught doing something naughty comes round and round because it has the power to get our own pulse racing. We might never have been carrying on an elicit affair with our elder brother’s foreign princess bride, but we do know how we felt when we almost didn’t get away with something we knew we shouldn’t have been doing. And very often, we find that funny, because laughter is a way of reducing tension. Comedy is famously culturally specific, but very, very often is about walking the line between okay and not-okay and occasionally slipping off.

But there are some very different things in the story of Vīs and Rāmin, too, that point to how contingent ‘normal’ really is.

There are plenty of aspects of being human, and especially about being human in groups, that are often or usually true. There’s almost nothing about being human in groups that is always true.

Take Vīru, for example, Vīs’s brother and husband. Most cultures have had rules about consanguineous marriage. Those rules are pretty varied.

In Britain today, it is illegal to have sex with a parent/child, brother/sister, uncle/aunt, nephew/niece. More distant relationships are fine, legally, but some, including between first cousins, are frowned on by some parts of society, and actively preferred by others.

In the Byzantine Empire, by contrast, marriage was usually forbidden up to seven degrees of consanguinity. I don’t even know what that would make somebody to you: some sort of Xth cousin very removed?

Societies have disagreed over whether adoption, step-parenthood or relationships like Godfather/Godmother count in the same way. (For Byzantium, no surprises, considering how careful they were over blood relations, they did. No marriage allowed within seven degrees of the family of your Godparents either… In practice, presumably an awful lot of people got married within the prohibited degrees because of just not knowing enough people to find anybody outside them!)

But ask lots of people about this vast complexity and they will say that everybody knows you can’t go about marrying… whoever my society says you can’t! We humans are very good at normalising our own ‘common sense’.

It’s obvious if you’ve grown up in Britain that you can’t marry your brother or sister! (Or parent or child or uncle or aunt!). Eew, eew, eew!

In Byzantium it might have seemed pretty obvious that you can’t marry your Godmother’s cousin. That would just be gross!

Then a story like Vīs and Rāmīn reminds us that all of these conventions are, to some extent, made up. (Note: I’m not advocating for or against anything here or suggesting that ‘made up’ things don’t matter! Societies are basically big agreements to make up things together and they are critical to… well, pretty much everything, but because their foundations are made up, they can be very varied and flexible.)

There is quite a lot of debate about how often close family marriages actually happened in the Parthian or later Sasanian Empire. It may have been quite rare. It may have happened mostly at times of crisis, when a dynasty was trying to shore up its power. But, whether it was common or not, it was evidently okay. It wasn’t gross or forbidden or possibly even weird.

In the same vein, it can seem normal, especially if you’ve grown up in Europe, the US, Australia, Canada or New Zealand, to think that the Roman Empire was the way to be a powerful ancient empire. Even sources from the ancient world can sometimes make it look as if the Parthians spent their whole time thinking about and fighting the Roman Empire but, apart from one bit where Mo’bad goes off to fight the Romans for a bit because he just needed to be somewhere else for plot purposes, this story is a reminder that the Parthian world was exactly that: a working, complex, imperial world with its own rules and conventions and ideas of power.

It seems like a world in which women (at least royal ones) might have a bit more independence and power than they often had in the Roman Empire and where the nominal chief emperor had quite a bit less.

I can’t wait to read the full text. There will, without doubt, be a thousand more moments of ‘Oh wow! That’s so similar!’ and a thousand others of ‘Ooh, that’s so different!’ and among all the good reasons for doing history that remains the best one, for me.

The wonder of being human, from a historical perspective, always seems to me to be how much we have in common but at the same time, what different worlds we are capable of creating. History reminds us that the future is not pre-determined: the way we have often done things or almost always done things is not the way we have always done them or the way we must always do them. And we don’t have to idealise a time in the past as better or perfect to see what if we’ve been different before, we can be again. Even if we’ll still probably enjoy a good ‘romance-adventure-journey’ montage!

The term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ has been hotly debated in recent years and there are good reasons why many scholars now don’t use it or use it in very specific ways. The best current discussion of this is: Naismith, Rory, ‘The Anglo-Saxons: Myth and History’, Early Medieval England and Its Neighbours, 51 (2025), p. e1, doi:10.1017/ean.2024.2. However, if you’ve heard of this as a medieval ‘Greatest Hit’ then it will have been under the name ‘The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’, which is why I use the term here.