Florence is full of beautiful things and I hope to go back there and spend more time admiring them, but my favourite sight when I was there, with many thanks to a friend who pointed it out, was not, in conventional terms, a beautiful thing.

I absolutely love the archaeology and material culture of waste and water management. It is often the lowest level of an archaeological site and so likely to be left when other parts have fallen down. It is a testament to human ingenuity in dealing with something we all share: the need for water and the necessity of disposing of waste. It can be excitingly complex, especially for somebody who doesn’t think well in three dimensions. It’s just really cool!

Water and waste management, though, have also been a focus for major public messaging across many periods and regions. Think about the aqueducts of the Roman Empire, which were celebrated as public works and associated with the names of the emperor(s) who commissioned or repaired them.

In Telangana, where I’ll be moving in about six weeks (eek: no I have not started packing…), medieval step wells served a similar function. They provided a valuable service to communities and were well-publicised charitable projects by kings of various dynasties.

The fascist states of twentieth-century Europe, though, brought the modern, industrial capacity for branding to the long-standing interest of governments in showing that they were on top of water management, hence that fascinating fascist era manhole cover in Florence.

It declares itself to be fascist - look for the fasces, the bundle of sticks bound together as a symbol of strength in unity. The fasces were originally an ancient Etruscan symbol, found in the Italian peninsula from at least the first millennium BCE. Like the adoption of the swastika in fascist Germany, a symbol which can be found across Eurasia from deep antiquity, the fasces (which give us the modern term ‘fascism’) were appropriated by something very new to project an appearance of something very old.

There is another detail next to those fasces, though: a date. Look in the top right of the image and you will find AN XII, an abbreviation of ANNO XII, or ‘in the twelfth year’. The twelfth year of what?

This manhole cover dates from 1934 in the Common/Christian Era, or the twelfth year of the era fascista in Italy. The new calendar was introduced by the fascist regime in 1926, which was already Year 5 of the new calendar, which was declared to have begun on 29th October 1922.

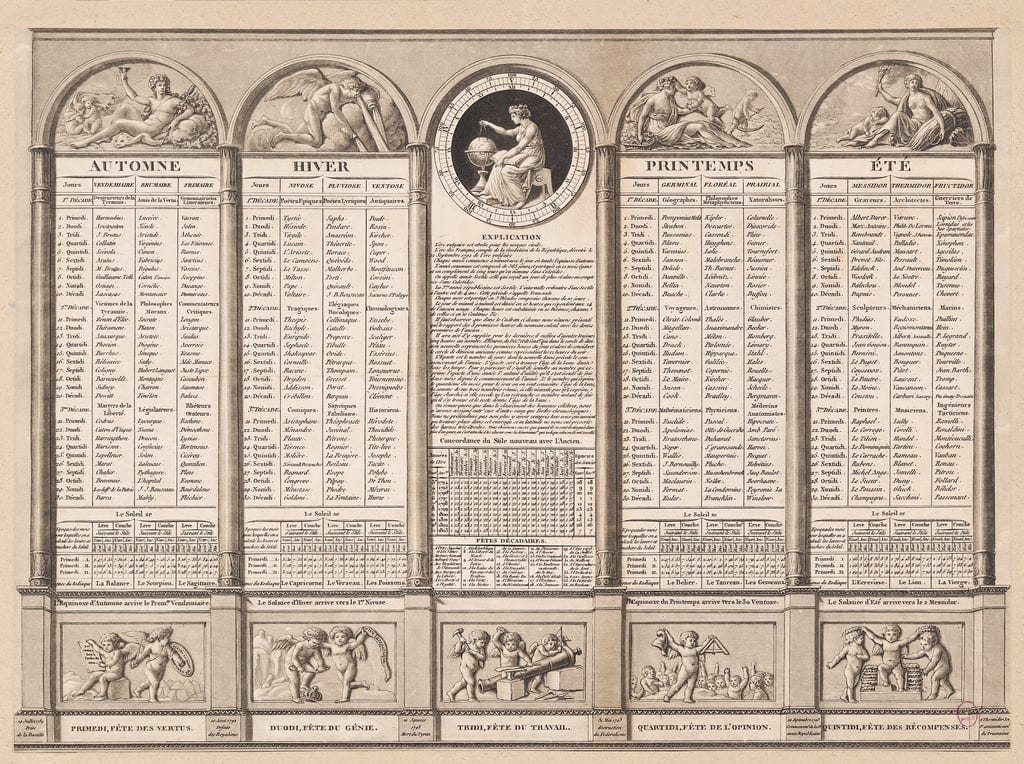

Mussolini’s Italy was certainly not the first modern regime to try to start a new era. Famously, the revolutionary government in late-eighteenth-century France tried to change not just the year, beginning again at zero, but also the months, weeks, days and hours, to a brand new and decimal system.

The Khmer Rouge government in Cambodia declared in 1975 CE that it was going back to Year 0 as part of its transformation of the country, resetting the calendar alongside attacks on signs of modernity, sentiment and any resistance to the revolutionary government.

Perhaps one of the most mind-boggling efforts to reset time by a modern regime comes from the Soviet Union, which for eleven years from 1929, tried to dissolve a common calendar completely. Instead, the workforce was colour-coded and each colour group assigned its own five-day ‘weeks’.

Now, multiple and different calendars have existed for as long as people have been counting time. Even in one state with which I’m familiar - the Byzantine Empire of the medieval East Mediterranean - one could (and people did!) mark time by any, or a combination of: time since the Christian creation of the world (Anno Mundi = in the year of the world), time since the incarnation of Christ (Anno Domini = in the year of the Lord), time since the beginning of the reign of the current emperor, time since the beginning of the tenure of the current patriarch of any one of the five major Christian sees (Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem or Alexandria), the year of office of specific consuls (since these traditionally held office only for one year), time since the agreed date of the foundation of the city of Rome in what we would consider 753 BCE (ab urbe condita = from the founding of the city. No, you didn’t need to ask which city.) And I could go on, with local dating by specific events, the foundation of institutions and on and on.

A tendency towards making time more measurable and more legible across the world has accompanied global transportation and technology. Famously, in the UK, standardised time became necessary with the arrival of the railways, when it started to become impossible to set train timetables if 10am was not the same in London as in Birmingham. Developments in clock-making enabled this standardisation and for most of us now, it has become normal to think about time as something that is what we call it: this is 2024, tomorrow is Saturday, the time now is whatever it says on your watch or phone.

Maybe you find out your watch or your phone is wrong, and that, too, seems like something we can be certain about: even if our personal measuring devices are not quite up to scratch, we know that there is a right answer.

And yet, alternative time is actually all around us. From the major lunar calendars used within Islam and in China to set the date of major festivals and everyday religious or ritual observance, to the variations between Julian and Gregorian calendars in the Christian world, which mean that Catholic, Protestant and Evangelical Christians tend to celebrate Christmas and Easter a few days earlier than Orthodox Christians, historical legacies of diverse time are everywhere. At a smaller scale, the island of Foula in the Shetland islands of Scotland remained on the Julian calendar when the rest of the UK switched to the Gregorian calendar and is now slightly out of sync with both. It doesn’t seem to matter much: there are no trains! And the population is small enough to manage the everyday conversions between island time and outside time without anything breaking down.

Nevertheless, the fascist era manhole cover, the Khmer Year 0 and the French revolutionary calendar are not quite like the standard diversity of human counting of time. They were trying to do something else. They were trying to reset time, to start again. The idea, visible in the desire not just to restart the count, but in many cases to reconfigure how people organised time, was to begin a new future and at the same time to go back in time. In each case, the justification for the calendars and the governments alike was to ‘undo’ mistakes made, to ‘sweep away’ the old and return to something purer.

Each of them looked for a new future in a distant past.

The fasces, with their huge antiquity in the peninsula, and Roman numerals for the new calendar proclaimed the particular past that fascist Italy was interested in reclaiming. In no case, though, did these political systems seek to return to anything like a historically accurate version of the past. That wouldn’t do at all! The new would be a perfection of the old, because, after all, the old, however good it was, couldn’t have been perfect or why would there need to be a reset?

At the heart of any effort to ‘start over’, to ‘reset time’ lies an impossible fantasy: to make both the past and the future completely legible, stripped of its complexity, cut loose from the maddening, wonderful impossibility of making people ‘standard’, of fixing our ways of being in legible, transparent order.

Perhaps this is why efforts to create new calendars for radical social movements often look slightly absurd in retrospect: a curiosity, a sign that the ideologies themselves were always unworkable (and frequently malign). Because at their root lies the irrevocable truth that ‘we can’t go back the way we came’ but nor can we ever clean the slate and start from nothing, nowhere and no-when.1

Working with the past as it exists around us, living with it, learning from it, retelling it and re-examining it, reminds us that we are collectively so much more than any narrow imaginary of a ‘perfect’ society, or person, or past, or future. The power of history is not in the answer, but in the conversation.