Hello, hello,

Welcome back to Coffee with Clio. Grab yourself a steaming mug of your favourite (de)caffeinated beverage and take a break from everyday for yesterday (or maybe a bit longer ago than that…).

It is now definitely winter here in Yorkshire. This week we had snow and there are Christmas decorations and gritting lorries everywhere. It is also dark by about 4pm, which annoys our cat. We don’t let him out at night, so his days have gotten dramatically shorter and the only thing for it is to spend the evening sitting on me, sleeping resentfully.

This week, I’d like to answer a question that a reader asked. It was part of a conversation about the Roman Empire, based on an earlier post of mine. However, it was a change of direction and needed a bit more thought than I had at the time and there have been a lot of deadlines lately. (One day, I’ll tell you all about this year but I’m a historian: I definitely like to get through things before I start reflecting on them!)

Anyway, dear reader, you know who you are. I’m sorry you didn’t get this answer sooner and I hope you don’t mind me sharing it!

The question was:

What got me interested in the Byzantine Empire?

Why people study what they do has always been an interesting question for me and hopefully also for you, especially if you are a new reader here. What follows doesn’t explain all of what I do or how or why, but it definitely covers some of it.

Aptitude and interests definitely played a part: I love words, old things, how people and communities work, and books and libraries, so history was maybe never a big surprise.

That only gets us as far as the entire human past, though. How do people narrow down from there?

There are about as many answers to this as there are historians, but they cluster around a few poles:

Something personal

Something local

An inspirational teacher

An inspirational experience

None of the above

A combination of two or more is common.

For me, the answer is mainly ‘none of the above,’ which isn’t that unusual.

Byzantine studies, though, is still a slightly unusual choice, even among ‘none of the above’ historians, and explaining why involves posing the alternative question:

Why not Byzantine studies?

There are lots of reasons why ‘Byzantinist’ isn’t many people’s answer to ‘what do you want to be when you grow up?’, especially in the English-speaking world.

First, it is really quite easy never to have heard of the Byzantine Empire. I hadn’t until I was around 18. Outside the regions of the Mediterranean that were once under Byzantine rule, and which are still majority Christian today (so, broadly, Greece, Cyprus, the Balkans and parts of Italy), the Byzantine Empire is often not part of national or world histories.1

Second, it is quite hard to define. The term ‘Byzantine Empire’ is a bit of a misnomer. The label only became popular in the sixteenth century, after the empire had come to an end, and mostly in places where it had never been.

It was a way of distinguishing ‘the Romans’ (you know: togas, centurions, erotic poetry, incredible feats of engineering and popular brutality, as I wrote about here), from ‘the Romans,’ who carried on being Roman after the empire lost control of its western provinces. Those losses did include Rome, so I can sort of see an argument for a change but the people involved didn’t. They carried on calling themselves Romans.

These other Romans ruled a smaller empire, based in the Eastern Mediterranean. Their capital city (‘New Rome,’ as they understood it) was in Constantinople, modern Istanbul. Their main language of government and literature was Greek not Latin and they were Christian.

When and how these changes took place and what people thought about them at the time are all major topics in Roman/Byzantine studies, but mostly the Byzantine Empire refers to the Eastern Roman Empire from around the 4th century CE (when Constantinople was made the new capital of the empire and Christianity became the imperial religion), until 1453, when the Muslim Ottoman Empire took over Constantinople (which became Istanbul).

That cultural triad - Greek-speaking, Christian, ruled from Constantinople - is probably the best simple summary of what ‘the Byzantine Empire,’ or ‘Byzantium’ refers to.2

A third reason lots of people don’t study Byzantium is because it has, historically, gotten very bad press. For many of us, the word ‘byzantine’ refers to something needlessly complicated!

And a fourth reason is that, if the (ancient) Romans look weirdly ‘like us’ (which I wrote about here), the Byzantines look weirdly ‘not like us’.

Flick through some books of Byzantine history and you will find a lot about long-running, sometimes even violent debates about whether Jesus was fully human or fully divine, or a bit of each and, if so, exactly which bits were which.

One of the key turning points in histories of the Byzantine Empire is a two-century-long conflict over whether or not it is okay to paint images of holy figures, often referred to as ‘Byzantine Iconoclasm’. To make matters more complex, even the debate itself was often had in images!

This page from the so-called Chludov Psalter, made in around 850 CE, shows Christ being crucified in the upper right. As per the biblical account, a Roman soldier taunts Jesus by offering him vinegar on a sponge on a stick when he complains of thirst.

At the bottom of the picture, beneath the hill of execution, a Byzantine who does not agree with the use of holy images (who the makers of the Chludov Psalter saw as grievously wrong), uses an identical sponge on a stick to whitewash over an image of Christ.

Notice how the colour of the man’s robe is identical to that of the Roman soldiers. The jars for the vinegar and the whitewash are exactly the same shape and the face of Christ on the cross and on the wall are the same, too. The Iconoclast, painting over the image of Christ, argues the illustrator, is committing the same sin as the Romans who defiled and mocked Christ on the cross.

The empire can come across as very concerned with questions that may seem bizarre, at least outside the confines of a theological seminary or university department, yet these questions seem to have caused street riots, rebellions and civil wars.3

So, once more, you may ask, why Byzantine studies?

Some of the answer is just happenstance. I happened to pick up a book at a secondhand store. And then I happened to read it (unlike the many books on my shelves that I’m getting round to… any decade now). And this happened to happen exactly before I neede to choose which courses to take in my history degree.

I’d planned to pick things I felt I had some sort of handle on, or personal connection to, like the Second World War.

Instead, I picked a course about the Byzantine Empire, and that was lucky. Most universities don’t have one, because, as I’ve also talked about previously, historical topics that are popular tend to stay popular and vice versa.

What was this book, you might ask, that began a lifetime journey into Byzantine seas?

It isn’t necessarily one that a lot of Byzantinists would approve of.4

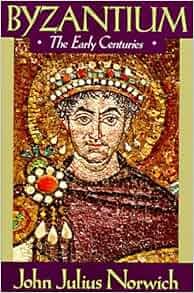

John Julius Norwich’s history of the Byzantine Empire is sensationalist, free-and-easy with the evidence at times, and rooted in some unhelpful stereotypes about Byzantium (decadent eunuchs abound!) but I learned something valuable reading it.

There are different kinds of good history that serve different purposes. Making sure that more people have heard of something, and can maybe get excited about it, is a good kind of history even if it isn’t always completely rigorous.5

Community

The other thing I discovered as I studied was the concept of a ‘Byzantinist’.

Not all areas of historical study have a strong sense of community.

Byzantine studies isn’t a tiny field, but it is small enough that I quickly began to spot the five or six major journals, the really important museum collections everybody mentioned, and how people regularly referred to personal connections in footnotes and acknowledgements.

Although I didn’t realise it consciously then, it was important that I could imagine what ‘being a Byzantinist’ would look like. For somebody pretty new to the whole world of universities and scholarship, that mattered.

A Byzantinist was not just somebody who studied the Byzantine Empire. It was somebody who had published in Dumbarton Oaks Papers or studied at Dumbarton Oaks itself (a beautiful, wacky, place in Washington D.C. with some of the best Byzantine studies collections in the world).

A Byzantinist met up with lifelong friends at the same conferences and events.

My spectacles were rose tinted but showing me something real. As I got more deeply into the community, I found a shared passion for something and the networks that creates, even if the interpersonal stuff can be a bit more complicated than my teenaged imaginings.

Who I am

These days, then, Byzantinist is what I am because it is a huge part of who I am. It has given me friends and taken me to incredible places. It is a web of colleagues of colleagues and students of supervisors that works a bit like the Masons (with less Egyptology and apron-wearing): across the world, there are people I could reach out to if I were visiting or stranded.

There were some nudges, though, that go back to other factors from my list of reasons why people study things. Only with hindsight do they seem to join up into something that pointed the way to here.

No. 1 still doesn’t apply. Byzantium is definitely not local to Wolverhampton!

There is a personal link though. Sort of.

My grandfather was a Croat from what is now Bosnia Herzegovina (then Yugoslavia), who came to the UK after the Second World War.

I don’t remember him well but the snapshots are clear and powerful.

(I smell the skin of a tomato, ripe from the sun, and I can see every detail of his greenhouse and the lines on his hands as he bends and holds it under my nose and, for a fleeting instant, I hear the sound of his voice, a fragment too short to be a word. A gif of childhood. Maybe my earliest memory?)

And he has always been a part of my life in stories from parents, uncles, and cousins.

At 11, I was incredibly fortunate to study Russian and it seemed like a connection to him. Croatian and Russian are are both Slavic languages. I figured if I learned Russian, it would make learning Croatian easier and the sounds of the language seemed like something he might have recognised.

Around the same time, we went on holiday to Crete and, as we entered a small chapel, I remember my mom telling me that the church reminded her of my grandfather. He was Catholic, not Orthodox, but I don’t think she was talking about theology: this was a feeling of stone and sun, the glimmer of gold and incense smoke.

She was responding to something shared, in different ways, across the Eastern Mediterranean. Neither of us knew that a huge part of that something was Byzantium.

Orthodoxy and the Empire that Would not Die6

The kind of Christianity that developed in the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire is usually called ‘Orthodox’.

This isn’t the place for a potted history of Christianity, but, as it happens, Orthodoxy, like Byzantium, is another term of convenience. It means ‘correct belief’, so Orthodox Christianity literally means ‘correct Christian belief’.

As you can imagine, there aren’t too many Christians who think of themselves as practicing ‘incorrect Christian belief’. In the beginning, then, Orthodox Christianity wasn’t a special kind of Christianity. It was just Christianity.

These days, Orthodoxy is often contrasted with Catholicism, but ‘Catholic’ means ‘universal’, so again, it isn’t really possible, if we go back to the start, to imagine Christianity that wasn’t part of a ‘universal church’.

Originally, both Orthodox and Catholic Christianity were one. (Protestant and Evangelical Christianity, the other two broad groupings today, had not yet happened.)

Over time, though, as Christianity became more and more popular, especially from the 4th century CE, people inevitably disagreed about exactly which beliefs were correct or universal.

Practicalities got in the way, too. In the Western Mediterranean, people mainly spoke Latin for official purposes. In the Eastern Mediterranean it was Greek. From the fifth or sixth century onwards, fewer people spoke both. Misunderstandings happened. And the ways people practiced Christianity just became gradually more different.

Scholars start to find it simplest to talk about two broad blocs of Christianity - a Catholic one to the West and an Orthodox one to the East - from some time in the Middle Ages, though the division was never simple.

The Byzantine Empire and Orthodox Christianity were never exactly the same thing. There were lots of Orthodox people outside the empire, spread as far afield as East Africa and South and East Asia, as well as Eastern Europe, and people who were not Christian lived inside the empire, including Jews. But the link was close.

The empire defined itself by its Christian faith. Some of its largest buildings were churches. Its emperors were depicted being crowned by Jesus and protected by the Virgin Mary.

That is why those debates about the nature of God were so important.

Who we are

Honestly, when I first started reading about those debates, I was as baffled as a lot of people.

Did Jesus have a single spirit that was both divine and human at the same time? Or did he have two spirits, one human and one divine that co-existed perfectly together? Or did he have two spirits but one energy that united them?

This is where inspirational teachers came in.

Some brilliant scholars helped me to get past a huge wall of unfamiliarity and one day I realised that I didn’t have to agree or disagree with the debates or explain them as substitutes for things that made sense to me (e.g. people weren’t really fighting about Christ’s two natures. They were really fighting about class or ethnicity or regionalism and these were just the labels they used, like football fans from different teams).

It all made more sense if I accepted that this was a different world. My job was to understand how the people made sense of things and how that made them behave.

And curiously, the more I got to know the people of that past, the less strange they seemed. They definitely cared about and believed things I don’t, as lots of people do today, but they were also very relatable.

They found ways to cope with cold and heat, to farm, cook and eat. People fell in love and got married. People fell in love with people who were already married and got into trouble. People fought and danced and read and sang and built things and tore them down and worried about the price of fish.

Christianity was usually the way to explain their hopes and fears and to seek guidance. The pictures of holy figures, usually called ‘icons’ in English, are one of the most distinctive features of an Orthodox Church today and provide a means to speak directly to holy figures.

If you look at a Byzantine image, there is meaning packed into every gesture and figure. Like coins, which I’m also obsessed with, I remember when every one looked a lot like all the others, then they started to make sense, addictively building the outlines of a real world full of complicated, confusing, fascinating people.

In the end, there always was something personal about my pull to Byzantine studies, even if it wasn’t direct or simple. There was inspiration from people and places, but most of all, I was drawn to a time and a place that didn’t seem to work like any world I knew and that, as a result, made the things that make us alike all the more obvious.

The largest area missing from this list is the modern state of Türkiye, which was the heart of the empire. As a majority Muslim country today, the relationship of Türkiye to its Byzantine past is fascinating but it would be fair to say that in popular history, it plays a fairly minor role.

My go-to on this and the empire in general is Stathakopoulos, Dionysios, A Short History of the Byzantine Empire, I.B.Tauris Short Histories (I.B. Tauris, 2014).

I do not mean to suggest that these debates, or the correct conclusion to them, as each believer sees it, do not matter today. They do, enormously, to millions of Orthodox Christians all over the world. However, debates about the nature of Christ are definitely less likely to be heard in the supermarket or public pool!

The work comes in three parts, covering early, middle and late, or a single abbreviated volume: Norwich, John Julius, A Short History of Byzantium (Penguin, 2013).

The exception to this is bad history, which is more dangerous the more popular it becomes. John Julius Norwich’s writing about Byzantium is not aimed at scholars and it does things that scholarly history shouldn’t, but it tells a great story, makes complicated things digestible and does not manipulate the reader to think untrue and hateful things about the present by lying about the past (be they lies of omission or commission). Things that do that are bad history and there is no defence for them, including ‘but what if it means more people finding out about the past?’

This heading draws on the title of an influential work that helped to explain how the empire survived several of its most important setbacks, in terms of logistical and administrative capability, but also a fierce sense of identity and unity around religion: Haldon, John F., The Empire That Would Not Die: The Paradox of Eastern Roman Survival, 640-740 (Harvard University Press, 2016).